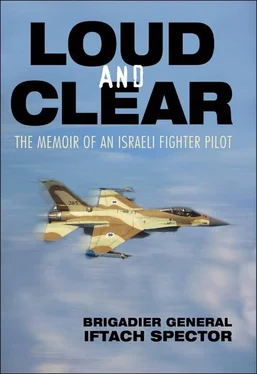

AND THERE WAS THE ISSUE of the aircraft’s vulnerability to hostile ground fire. The antiaircraft defense around Tammuz was considerable. The reactor and nearby Baghdad were circled with rings of SAM batteries and antiaircraft—not to speak of MiGs from nearby airfields. The radar coverage was perhaps only equaled around Moscow. The chances of some of us getting hit were well above zero, and the F-16 carried with it many unknown factors. It was a new aircraft with a single engine, and nobody knew how durable it was under fire and for how long it would stay airborne and get its pilot out once it took a hit.

Some protested against the use of F-16s on this dangerous and uncertain mission, and suggested sending the double-engine F-15s instead. The large F-15 seemed so much more massive and robust. A heated debate broke out in the air force commander’s office; everybody wanted the mission for himself. But Ivry knew he had bought jet fighters, not toys, and to become the backbone of our attack force they must prove themselves under fire. Ivry knew it and I knew it, and in the last discussion in his office—the two chiefs of the opposing tribes, and a few technical people participated—we both were on the same side. Ivry concluded, “This is what we bought the F-16s for. They can do it, and they will,” and I came out holding the bag.

To the delicate question the government asked him, how many of the attackers were likely not to make it back, Ivry came up with a percent “casualty estimate.” He calculated the number from past missions with limited similarities, according to the methodology of operational research. Then the term “casualty estimate” began to make the rounds, and the thinking regarding this nasty subject got to Ramat-David and the few pilots who were preparing the operation, drawing maps, calculating fuel quantities and experimenting with long-distance flight and attack profiles. These pilots began to wonder how many of them would end up staying in Iraq. Somebody estimated that we would lose just one; others put it at two. Later, the ugly question of who among the chosen eight had the best chance to be hit came up, too. Everybody thought he might be the one. There were even secret betting pools.

And all this time, above us, decisions were being made, then canceled. A few times the government decided to go for it. On one occasion we had even started our engines, and the mission was aborted.

“You don’t have the slightest idea,” Ivry told us, “of how many times we kept all that shit from falling on your heads. You had F-16 squadrons to build, and had we driven you crazy the way they drove us… ”

As an example, he presented a handwritten note sent to him by the IDF’s chief of staff, Raful, from one of the cabinet meetings.

“I told them,” wrote Lieutenant General Raful to Ivry, “it’s either-or. Either you decide to do it, or stop driving us crazy.” Raful, who sat next to me with his sturdy arms folded on his considerable belly, grunted, “Had I known you kept all my notes, Ivry, I would have written twice as much.”

Laughter filled the room.

AND THERE WAS ALSO a personal secret. Ofra, Ivry’s wife, told us that on the day before the attack she and Ivry had visited Tel Nof.

“On the way back home, right near Mughar Hill, David stopped the car.”

Mughar Hill is a high, barren, red clay hill, and everybody who grew up in the area knows it. David Ivry was a native of the nearby township of Gedera, and so was Ofra. Surely as kids they picked anemones on the hill in the winter, just the way Ali and I did. Kibbutz Givat-Brenner is on the other side.

“And standing there, David told me,” Ofra continued, “that tomorrow the atomic reactor at Baghdad would be hit.”

Ofra is a delicate woman, and excitement showed on her face. Silence fell over the big room. This operation had been absolutely top secret. Nobody was supposed to say a word about it. David brought his head closer to Ofra’s in an affectionate way and she continued, as if apologizing, “I didn’t believe it. This was the one and only time during our whole life together that David had told me about a mission. And how had it suddenly come to be the reactor? All Israel was talking about Lebanon then.”

When they went to bed, David fell sound asleep, but Ofra didn’t shut her eyes the whole night.

Nobody told Anat Shafir, Relik’s wife, about the forthcoming operation, “and just for this reason our marriage stayed intact.”

Anat is a sculptor who works in iron. The story of the attack on Tammuz, when she finally learned about it, she imagined as “a very precise and sturdy structure of iron pieces, welded into one by a superb artist.” For a moment she caused all of us to see this operation through different eyes, those of an artist. She read her comments from her notes.

“The full story got to me years later, and suddenly I realized what a risk we took there. Only then did I grasp that we all were living on borrowed time,” and here she paused, struggling with feelings brought on by her memories.

Relik, her husband, Nahumi’s deputy, took over and told his own story: “At the end of the last briefing, Major General Raful got up and said to us, ‘The fate of the Jewish nation is in your hands.’ Then I remembered my grandfather.”

“My name is Israel,” explained Relik. “My parents named me after my grandfather. My first daughter’s name is Rachel, after my father’s sister. Both Israel and Rachel died in Stutthof, a Nazi concentration camp in northern Germany. They were taken there from the Vilna Ghetto, in Lithuania.”

I thought, Good God, where are they going with this?

True, I was expecting some odd stuff to come out here, but nothing like this. I had never imagined that a tall, bright guy such as Relik might think when hearing Raful loading on him the fate of the whole Jewish nation such grandiose things as I might not return from this mission, but at least I won’t die the way my relatives did.

But he went on. “This was the first time in my life,” Relik revealed, “that my dead relatives came to me before a mission.” And then, a split second before the atmosphere turned morbid, he added mockingly, “After that, I didn’t worry anymore about fuel consumption. All I needed was to get there; no need for fuel to return.”

Laughter broke out and filled the room, breaking the tense silence that had reigned until then. Fighter pilots usually don’t talk like that. But although I didn’t have any such thoughts, I still keep to this very day a handwritten note another high-ranking officer sent me: “You won’t need fuel to get back.”

EVENING CAME, AND THE LIGHT coming through the large windows faded. Ali got up and switched on our many lamps, and the atmosphere in the room brightened considerably. Now it was my turn to tell my story. And first I had to explain for the thousandth time why I, the base commander, went on the mission to Tammuz. In most military organizations, colonels and general officers do not go on such missions. Colonels and generals are supposed to manage things from the rear, to sit in front of screens and give orders, not to pick up rifles and go with the enlisted men to the battlefield.

Why, indeed, had I gone?

I admit there was my fighter pilot nemesis—that “black demon” that Ali always accused me of having. It was there as always, urging me to go, see, and do. But this time that demon was not the whole story. There was an angel of my better nature. I was moved by a feeling of responsibility.

David Ivry thought otherwise. He ordered me not to fly the mission, but then the chief of staff, Raful, gave me a hearing. We were sitting in his car. It was very early in the morning, and we were waiting for the pouring rain to slacken so I could allow the amateur pilot general to take off in his plane to Tel Aviv. Those 1981 winter days made it a regular ceremony between us. I would get up very early and go out to see if the weather would be a problem for his level of experience, and at times I halted his takeoff right on the runway. He complained but always complied, and I believed he relished the drama. This time the rain was really heavy, so I got in his car and we had few minutes of privacy till a hole opened in the overcast.

Читать дальше