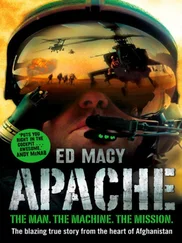

The course continued to explore the arsenal in the kind of microscopic detail that I thought would only interest the boffins who’d designed it. Little did I know that the lessons Captain Paul Mason taught me would be put into vigorous practice and have me reading more and more just to stay one step ahead of the Taliban.

In March 2003, while I took a break from the Apache to work on temporary assignment in Bosnia for SFOR (Stabilisation Force), George W. Bush and Tony Blair launched their ill-fated assault on Saddam Hussein in response to intelligence, later known to be highly flawed, that Saddam was harbouring weapons of mass destruction and Al-Qaeda insurgents. It was the start of a road that would eventually see us being assigned to the front line of the so-called War on Terror.

1 SEPTEMBER 2003

Middle Wallop

The Apache instructors, some still sporting suntans from their US training, were eager to start teaching us, but my first flight was going to have to wait. CCT1 – the first Apache pilot’s course – was being paraded in front of the camera; the British Army loved a team photograph.

Shuffling around in front of twelve, brand new, immaculately paraded Apaches were fifty-nine very proud people – the people who were busting their balls to get the Apache into service. With over half a billion pounds’ worth of assets behind us, the shot had to look impressive. With any luck, it would capture a team brimming with pride and confidence; never mind the fact that the road to initial operational clearance – the day that the Apache was declared fit for military ops – was still some way down the pike.

While most of the group grinned like chimps, the twenty pilots of 656 Squadron were hoping that the camera would be far enough away not to pick out our faces in any detail. To have our mugshots printed in newspapers and glossy magazines could already prove fatal.

The war against Iraq, in which George W. Bush had recently declared the United States victorious, had unleashed a storm throughout the Islamic world. A crew member of our deadliest attack helicopter was well on the way to becoming a highly valued target. The idea of being taken hostage and identified scared us all, but someone in front of me made light of it with a hilarious impression of our Taliban captor.

Before any of us could fly, we had to go through several weeks of ground instruction. We covered every Apache system in great detail. It had hundreds; we even had to learn about refrigeration in case an air-conditioning unit failed at a critical moment.

We were finally introduced to the sharp end of the Apache ‘capability matrix’ by the one and only Captain Paul Mason-basic revision of the complex world he had led four of us through the previous year.

We began with the 30 mm Hughes M230 Automatic Chain Gun, the cannon, attached to the airframe in a fully steerable mounting beneath the cockpit. It could be operated by both crew members. By selecting ‘G’ on either cyclic, or the gunner’s left ORT grip, it automatically followed the direction of your sight-TADS crosshair, FCR target or, if you were in Helmet Mounted Display Mode, to wherever you were looking through the monocle. The computer calculated the necessary compensation for the speed of the Apache, wind velocity and drop of the shell during its time in flight; all we had to do was point it at the target and pull the trigger.

The cannon was accurate up to 4,200 metres – over two and a half miles – but was most effective at less than half that distance. It fired ten rounds per second in pre-selected bursts of ten, twenty or fifty rounds – or, if we wanted, the whole lot in one go: 600 rounds a minute. Optimum effect – the ‘combat burst’ – was set at twenty rounds.

The shell was a 30 mm High Explosive Dual Purpose round, known as HEDP (pronounced ‘Hedpee’ by pilots) but commonly referred to as ‘thirty mil’ or ‘thirty mike mike’ by FACs and JTACs. Its shaped-charge liner collapsed on detonation to create a jet of molten metal that could cut through inches of armour. Fragmentation of the shell created its anti-personnel effect, but once detonated it also torched the target, making it devastating against buildings and vehicles.

US experience had shown that if pinpoint accuracy was required and sufficient time available, the gunner should use the TADS as his sight. When time was a factor the helmet-sighting system was as effective, but with an increased spread.

The stub wings of the Apache held ‘hard-points’ that enabled the helicopter to carry two air-to-air missiles and four underslung pylons for a range of weapon combinations, depending on the nature of the mission.

One option was to mount four M261 rocket launchers – nearly seven foot long with their black rocket protection devices and carrying nineteen CRV7 unguided rockets each.

We chose the CRV7 – Canadian Rocket Vehicle-C17 rocket motor instead of the American Hydra 70 because it was faster. Being able to hit more distant targets gave us a better stand-off distance. It also had 95 per cent more kinetic energy at shorter distances and 40 per cent better accuracy too. It’s a fast spinning, fin-stabilised rocket motor capable of being fitted with and carrying several different warheads up to eight kilometres. They would go further, but we wouldn’t need to fire from more than five miles away, we were told.

The most commonly carried warheads were the High Explosive Incendiary Semi-Armour Piercing (HEISAP) and the Flechette. The final choice was the Multi-Purpose-Sub-Munition, which Rules of Engagement (ROE) generally wouldn’t support. The MPSM – ‘the death from above’ – was a multi-purpose rocket, connected to the launcher by an umbilical cord that was hard wired to the weapons computer. It told the rocket how far to go before exploding above the target, whereupon nine bomblets – sub – munitions – would descend, slowed by a small Ram Air Decelerator (RAD) resembling a triangular yellow duster. As the sub-munition struck a vehicle its shaped charge would detonate, sending a high speed molten jet of copper through a tank or APC, killing everyone inside. The casing would also fragment on anything it touched.

Each bomblet would fragment into scores of red-hot, razor-sharp shards of steel, travelling at 5,000 feet per second in all directions. The only warning the enemy would get would be a pop above them; by the time they spotted the yellow RADs, there would be no time to run, drive off or take cover.

It was the perfect weapon for mounted and dismounted troops but had one serious drawback. On soft soil or sand, some would fail to detonate. To an unsuspecting child, the bright yellow dusters would act as an invitation to violent death or maiming. We couldn’t fire them without special orders, and even then we’d have to record the impact point and treat it as a minefield.

The HEISAP – ‘the beast’ – was a kinetic rocket, originally designed to sink ships. Its nose contained a heavy steel penetrator that would drive through the hull. Once inside, a delayed fuse would ignite the high explosive, ripping the ship apart and igniting its incendiary charge, which would stick to the internal alloy structure and other materials; it wouldn’t take many to set off multiple inextinguishable fires.

I thought of the fatalities aboard HMS Ardent , Sheffield and Coventry and the merchant vessels like Atlantic Conveyor and Sir Galahad in the Falklands. The majority of them burnt to death.

The most fearsome of our three weapons, however, was the one that carried no explosive to its target at all: the Flechette rocket – ‘the swarm of death’. Its warhead contained eighty tungsten flechettes, each dart weighing eighteen grams. Just less than a thousand metres after firing, a small charge would push two forty-dart cradles out of the nose of the fast spinning rocket. Centrifugal force would spread them into a conical pattern. A pair of rockets would suffice against most targets, but if we increased the distance we would need to fire more to ensure a kill, or ‘probability of hit’.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу