‘Helloo, Ed!’ He breezed into the lecture room. ‘Are ye ready to go flying?’

I tried to pretend that it was no big deal, but Scottie wasn’t having any of it. ‘Och, come on, Ed, you’re allowed to show a little appreciation. You showed me the ropes in Ireland; now it’s my turn. You’re going to love this – I guarantee it.’

The lucky bugger had spent a few months learning to be an Apache instructor in the wide open spaces of Alabama, flying sorties from Fort Rucker after finishing the Weapons Officer’s Course with me last summer.

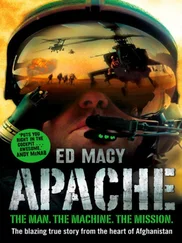

We walked into one of the specially revamped hangars. Twelve Apaches lay waiting under the arc lights, each with only a few hours on the clock. The tips of their rotor blades were rigid and interleaved to make the most of the available space. Scottie gave the nearest a reassuring pat on the nose. ‘I don’t think there is anything I could tell you about this that you don’t already know,’ he said.

I grinned. ‘I could build one in my garage if you gave me the bits.’

He curled his finger and beckoned me to follow him. We walked around the stubby wing on the right-hand side of the aircraft and paused beside the fuselage. I was finding it really hard to remain calm.

What never failed to impress was the sheer size of the Apache; the mighty Chinook that could carry fifty-five troops in the back was only a little over two feet longer than this two-seater. It was twice the length of a Gazelle and considerably bigger in volume. Up close, it was angular and ugly. The hangar was enormous, but getting twelve in was like solving a giant jigsaw puzzle.

My mouth had gone dry.

Scottie pulled himself up onto the wing. I jumped up, too, and watched over his shoulder as he opened up the cowling that shielded one of the two RTM322 engines and demonstrated how to inspect the oil levels – one of the pilot’s many duties before takeoff. Satisfied, he proceeded to check that the intakes were free from obstructions and then opened up the gearbox inspection hatch on the wing, just forward of the engine intake.

Back on the ground, he opened up the access panel on the back of the wing that contained some of the communications equipment. We then walked down to the tail and checked the stabilator – the aero-foil wing that sat horizontally below the tail rotor. It was locked and secure, as was the tail wheel below it.

The inspection continued up the port side. Finally, standing on the top of the Apache, above and behind the pilot’s cockpit, I watched Scottie spin the radome, perched on the main rotor hub, over sixteen feet above the grey-painted concrete floor.

‘Aren’t you going to tell me what you’re doing?’ I said. ‘I am here to learn.’

‘Och,’ Scottie tutted, ‘you don’t want to be fussing yourself over stuff like this. Not today. Today is for flying, Ed.’ He pointed a manicured finger at his wrist, gesturing for me to take a look at the latest addition to his watch collection. ‘Though according to Mr Breitling, we’ve time for a spot of lunch first.’

I was about to voice my frustration when Scottie, knowing how much I wanted to get airborne, put his hand on my shoulder. ‘Climb down, Ed. Everything in its own time. This wee machine isn’t going anywhere. It’ll be ready to fly after we’ve eaten.’

By the time we returned, the ground crew had towed all twelve gunships onto the pan. Protected by an imposing razor-wire fence, they were accessible only via a set of electronically activated gates designed to accommodate an Apache with room to spare.

They were arranged in two rows of six, their noses pointed inwards like prop forwards about to lock heads in a scrummage. I handed my camera to another student, a guy called Pat Wiles, and asked him to snap away. As I shook Scottie’s hand I felt like I’d been preparing for this moment all of my life.

Scottie showed me how to swing myself into the cockpit using the grab handles in the cockpit roof. For today’s flight I was in the back seat, which was stepped up to give the rear-seater – the pilot on a normal sortie – visibility over the gunner’s head.

When I’d pulled on my bonedome, Scottie showed me how to adjust the monocle. Then, after running rapidly over the cockpit layout, he jumped into the front.

After closing the cockpit and going through our preliminary flight checks, I fired up the auxiliary power unit, a small gas-turbine that supplied juice to the aircraft when it was on the ground. A faint hum was quickly drowned out by the rush of the air conditioning. In front of me, screens and displays burst into life.

By following the procedures I’d become familiar with in the simulator, I bore-sighted myself to the aircraft by aligning my monocle with the BRU on the coaming in front of me.

I threw the engine power levers forward and the blades began to turn.

After a further round of systems checks, Scottie asked whether I was ready.

I’d been ready ever since he’d first bloody asked me.

The Apache was nearly seventeen feet from wing tip to wing tip, but its undercarriage track – six and half feet – was relatively narrow. Scottie warned me that this, coupled with the heavy FCR above the main rotor head, made the helicopter feel unstable while you were taxiing.

I told him I was good to go.

‘Right,’ he said in my ears, ‘we need to pull in a little power. Thirty per cent torque will do.’ He reminded me to look for the ‘ball’ – a solid circular graphic, bottom centre in my monocle. If it was to the left of its kennel when we were on the ground we were leaning to the left. It also acted like a conventional slip indicator in the air.

I lifted the collective lever slightly with my left hand, increasing the power. The Apache began to vibrate. Everything looked and felt good. I checked the monocle: in the top left it told me the RTM322 engines were reaching 30 per cent.

‘Okay, that’s enough power now – you’ve got sufficient induced flow to move the aircraft.’ Induced flow was the downwash generated by the main blades. Pushing the cyclic tilted the rotor disc forward. I could feel the Apache straining to be released.

‘Raise your visor,’ Scottie said.

‘Why?’

‘I need to see your face while you’re taxiing.’

I glanced up. His eyes were watching mine in the little vanity mirror above his seat.

‘Okay, Ed. Brakes off and remember to keep her bolt upright. If she leans left move the cyclic to the right. Push the cyclic forward to go faster and back to slow down. Got it?’

‘Sounds simple enough, Scottie.’

I glanced down to place my feet on the very tops of the pedals.

‘Don’t look down, Ed!’

‘Okay, mate, keep your hair on.’

I rotated the tips of my toes forward and the parking brake handle released with a loud clunk.

I pushed the cyclic a bit more and we started to roll forward. Suddenly, I started to panic. The helicopter felt like it was about to fall over.

I could hear Scottie laughing.

Ahead of me the yellow line curved to the right in a large sweeping arc towards the huge gates and safely away from the Apache parked in front of me.

‘Right, I want you to release the tail wheel – but, remember, be careful.’

I looked down for the button on the collective.

‘Don’t look down, Ed. One more sneaky peek and I’ll mark you down for not knowing your controls.’

I’d spent weeks learning where they were but I didn’t want to make a mistake and push the wrong button.

‘Sorry, Scottie. It’s nerves. Mate, I’m afraid to fuck up.’

‘Relax, Ed. This is the easy bit. You must learn where things are instinctively. It’s for your own good. Wait until you do the bag.’

‘What exactly is the bag?’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу