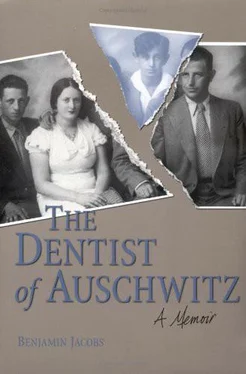

Benjamin Jacobs

THE DENTIST OF AUSCHWITZ

To my brother, Josek, who by the grace of God was spared from death in the camps

To my sister, Pola, my mother, and my father

And to others who were not spared to tell their story

Josek, Pola, Berek, and Uncle Schlomo in 1934, on one of Schlomo's annual visits to Dobra

In July 1985 I joined twelve Jewish men and women from the United States on a fact-finding mission behind the Iron Curtain. In the capitals of Poland, Romania, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia we visited a small number of Jews too old to leave for a beginning elsewhere. Most lived in Altersheims, homes for the aged supported by Jewish philanthropy. The Jewish life they had once known no longer existed, and anti-Semitism was still widespread. For the Jews, Hitler had won World War II.

When I returned to Boston, I sat back and took stock. I had to confront my obligation, and I began to speak out publicly about how and why nearly an entire people was erased from the face of the earth. In this process the small fragments of memory, fixed in my mind like holographic images, expanded and brought back my experiences in vivid detail.

But life does not always follow a straight road, as I had learned in my youth. One day, during a routine visit to the doctor’s office, expecting a clean bill of health, I heard the opposite: “You have throat cancer,” I was told. My good friend Dr. Goroll, as devastated as I, insisted that I be operated on the next day.

I imagined the worst. My speaking had become very important, for I had seen its effect on the young, how I had helped them understand the importance of resenting prejudices. Will I still have a voice? I wondered. The thought of becoming mute was overwhelming. I asked the doctors for a prognosis, but doctors are careful; they don’t speculate.

Fortunately the tumor was small and, thanks to immediate surgery and weeks of radiation, my voice changed little. But I knew the doctors could not forecast the future. A voice inside kept telling me, “Write—you may not be able to speak for long.”

I had to put my experiences on paper, and my work intensified. Comments from others poured in, echoing my own urge to write. This, then, is my story.

Although this book is the result of my recollections, some perhaps still locked in my subconscious, too deep for me to recall, it could not have been written without the valuable assistance I received from many sources. The sheer number precludes my thanking all of them. Nonetheless, I would be remiss not to thank a few.

In developing documentation of Auschwitz III, Fürstengrube, I am indebted to Tadeusz Iwaszko, writer and archivist at the State Museum at Auschwitz. I am grateful to Dr. Dirk Jachomowski of the Ladesarchiv Schleswig-Holstein and to Dr. Marienhöfer of the Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv in Freiburg, Germany, for documents concerning the Cap Arcona disaster on the Baltic Sea. I am particularly grateful to Edith Pfeiffer of the Hamburg-Südamerika Dampfschiffahrts-Gesellschaft and the Hamburg-Amerika line (Hepag) for company records, documents, and the history of the luxury liner Cap Arcona and for helping me obtain “top secret” documents concerning the bombing and sinking of the ship. I thank Barbara Helfgot-Hyatt, professor at Boston University and distinguished poet, who from day one encouraged me to write this book. I would also like to thank Ina Friedman, a prolific writer on the subject of the Holocaust, who read the first hundred pages of the manuscript and said to me, “Write. You are bitten with the writer’s bug.”

Special thanks to Arthur Edelstein and Marge Garfield for their talented revisions of the manuscript. Special thanks to Mark Dane for his valuable time and word processing equipment—for without it I would still be typing this manuscript on a typewriter.

In pursuit of this project, a very special acknowledgment goes to Dr. Karen E. Smith for her valuable advice.

Lastly, I thank my wife, Else, for keeping my spirits up during the more than forty-four years of our marriage. To the rest of my family, to my friends, and to my neighbors, my profoundest apologies for having been a hermit while writing this book.

I have purposely refrained from paving the book with notes and references so as not to trouble the reader who is not interested in research.

The mistakes, errors, and misjudgments are mine and in no way attributable to the people mentioned here, who have contributed so generously.

On the morning of May 5, 1941, three ancient trucks labored along a Polish country road, carrying 167 Jews from Dobra, a village in the Warthegau region of Poland, to a destination known only to their captors. It was spring, but the fields, which were full of colorful budding flowers, seemed lifeless on that gloomy morning. The songbirds, whose melodies usually filled the country air in May, were strangely quiet.

This was a dark day in our village. The Jewish Council, by decree of Herr Schweikert, the Nazi governor of the region, had delivered for deportation to a labor camp all Jewish men between the ages of sixteen and sixty, with the exception of one male per family. My father wanted to leave, and I volunteered to go with him, since my older brother was susceptible to ailments. So my brother stayed with my mother and my sister in the ghetto. My father and I were each allowed to take two bundles. My mother insisted that I take the few dental tools I had from my first year of dental training, along with my necessities. Little did I know then that those tools would save my life.

Mother’s face was lined with sorrow. Pola, my older sister, bravely held back her tears, and brother Josek promised to live up to his new role as head of the family. We all felt the pain of parting, and I turned my face away from them to find courage.

My parents hadn’t often shown affection for each other in public, and certainly not in front of us. But that day, for what was to be the last time, they embraced before us. As we left, Mama reminded all of us not to forget what we had agreed to do. “When this nightmare is over, we will all meet back here,” she said, with tears in her eyes.

On the way to the town school, our assembly place, we saw similar scenes. At every doorstep a small drama played out. A young girl cried and wouldn’t let her father go, seemingly knowing she would never see him again.

When we arrived at the school yard, SS men were everywhere. From their black uniforms and shiny boots to the skull and crossbones on their caps, they personified malice. Their belt buckles carried the ironic slogan “God with Us.” At the center of the yard stood the feared Herr Schweikert, along with Morris Francus, head of the Jewish Council. Two of the ghetto’s Jewish policemen were to come with us. Chaim Trzan, formerly a butcher, was perfectly suited for this job. But the other man, Markowicz, seemed out of his league, for he was a simple man with more bark than bite. Dwarfed by the tall SS men was the deputy of Jewish matters for Warthegau, Dr. Neumann. He was burly and middle-aged with snow-white hair and bright blue eyes. His stance spoke all: he was obviously in charge.

The Nazis knew how to pit Jew against Jew. They had created a Jewish Council, the Judenrat, for that purpose. In Dobra, the members of the council were self-styled community leaders with little conscience. With the help of the policemen whom they appointed, they wielded indiscriminate power over us. As difficult as it may have been for them to make the choices that no human should ever have to make, the members of the Judenrat primarily sheltered themselves, their families, and their friends from the privation and discrimination the rest of us had to face. Little did they know that, having sent their people to their deaths, they would in the end fall victim to the same fate.

Читать дальше