Josek had served two years in the Yellow Cavalry of the Polish army. Consequently, as war hysteria began, he was recalled and moved with his unit to the Polish border. September 1, 1939, came, and the tense waiting ended, for Hitler’s armies crossed into Poland and the Second World War began. Many people enlisted, and although it was against my mother’s wishes, I also tried to join up. However, the draft age in Poland was twenty-one then. The recruiting officer sent me home. “We’ll call you when we need you,” he said. Perhaps he already knew that fighting the well-equipped Nazi armies was senseless.

The next day the nearby mental hospital released all its patients, and hundreds of the insane paraded through the village, creating unbelievable scenes. One man mimicked Napoleon Bonaparte and claimed his armies were coming to fight the Germans. Another, marching as if on parade, saluted everything in sight. A pretty young girl, who seemed perfectly normal at first, suddenly burst into a confused tirade. It was pitiful and grotesque to see them all wandering the streets, staring off into the distance. When the Germans arrived, they put them against a wall and executed them.

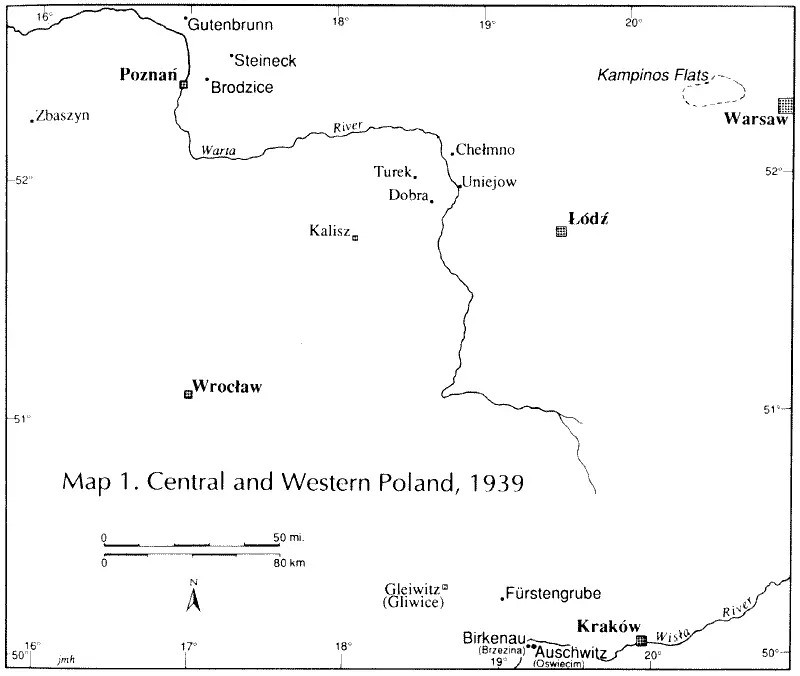

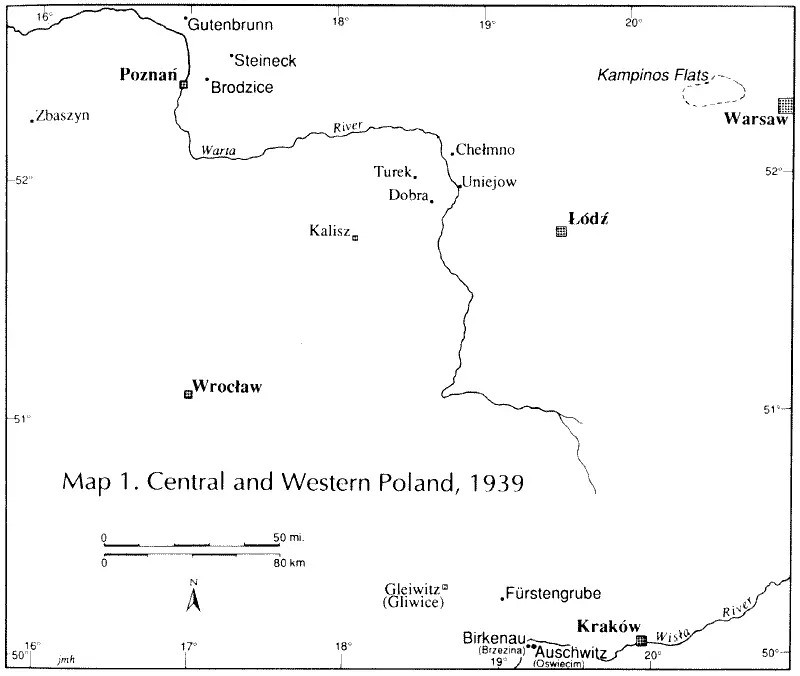

On September 3 the Nazi armies were just thirty kilometers away. They would soon be marching on the village. Our retreating soldiers vowed to take a stand and fight at the Warta River, the most logical place to resist the German advance. Our parents remembered a similar situation in the First World War, when our village changed hands several times. We prepared to leave. Just before we left, Josek appeared. “Our battalion,” he said, “had only rifles and lances. We were forced into a chaotic retreat.”

On Monday, September 4, we decided to leave Dobra. Our truck, an old Peugeot, seemed only to run when we did not need it, so to be safe Papa hitched two horses to a wagon and tied a third to the rear as a spare. After we packed the most essential provisions, clothes and valuables, blankets and bedding, we were ready to leave.

Grandpa refused to come with us. He did not fear German soldiers. “We fought them in the last war. Soldiers are soldiers. They won’t harm an old man,” he said calmly. And so we left him behind and entered a congested trail of war refugees.

The road was packed with horse-drawn vehicles. Some families even took their cows to provide milk for their children. There were few automobiles, for the army had confiscated them. Our horses were long past their prime, so we walked on foot behind the wagon at each hill. After an hour of slow travel, we heard the sound of approaching airplanes. At first we believed they were Polish. As they came closer, however, we clearly saw that they were not. Their unusual heavy roar and their black cross insignias were enough to tell us that they held the enemy. However fearful we were, we knew that they could see that only civilians were on the road.

When they glided down, we thought it was just to see if we were innocent civilians. We were sure they would not harm us then. Yet to our surprise, they fired at us, creating a mass panic. On the right was the Warta, on the left a field. Only a few trees lined the roadside. We were trapped, with nowhere to run. Since the vehicles followed one another only centimeters apart, every salvo of bullets took a toll. Our three animals rose and whinnied in alarm and tried to tear themselves free of the wagon. After the assault, the bombers rose up and departed, leaving death and destruction behind. Strewn about were dead and injured people and animals and wrecked wagons. This was my first taste of war. What followed convinced me of the validity of my parents’ concerns.

A few kilometers farther on we were spotted by two other German planes. Since there were no Polish airplanes to fight them off, we knew what to expect. We had good reason to be frightened. On the right of the road an embankment ran down to the river. Suddenly an army unit passed us on the left, pushing us onto the slippery, grass-covered embankment. Papa jumped down and gripped the horses’ reins close to their mouths to steady them. “Out of the way,” people shouted, jockeying for space. At that point Mama, Pola, Josek, and I were walking behind the wagon. Suddenly Papa yelled, “Untie the horse in the back!” Just as my brother did, a bomb fell into the river, and an explosion drenched the road. Our wagon was pushed further to the side, and gravity pulled the horses and wagon down into the river. The Warta parted. After a gigantic splash, the water churned, foamed, and sent our belongings and valuables to the bottom of the river. Large waves rolled away in a circle and then dissipated. Only ripples covered our property and the grave of two horses. We had nothing left except what we wore and the horse Josek held on to. The Stukas departed, and we were stunned and horrified. People who had seen what had happened streamed by. They were frightened, and everyone just wanted us out of the way.

Papa suggested that we go to his brother’s home in Uniejów. “We’ll stay there until the war is over,” he said.

Uncle Chaim, Papa’s older brother, was a very orthodox and extremely pious Jew who often neglected his family. He and his wife and nine children lived on the edge of poverty in a small apartment. Toba, his oldest daughter, had lived with us for years. But in the months before the war she had returned home.

When we arrived at Uncle Chaim’s, the apartment was empty. Like most people in Uniejów, they had realized that our army couldn’t stop the Germans. They too were probably heading eastward. We could not turn back; we had to go on. Dragging our one horse farther made no sense. We left it grazing in a field, and bedraggled, despondent, and hungry, we left Uniejów.

Outside the town we heard Papa’s name being called. It was Mr. Chmielinski. A few years back he had bought Herr Heller’s bankrupted estate. My father had had lots of dealings with him since. It was an unexpected miracle. “Wigdor! What are you doing here?” he yelled. “Is that your wife and your children? Come on, we will take you with us,” he shouted, unable to stop for us in the traffic.

His tall, spacious wagon, pulled by stalwart Belgian horses, was a stark contrast to our scanty rig. We jogged along next to it long enough for him and his son, Karol, to help us up. Then Papa explained our dilemma. Chmielinski and his wife sat in front. Mama and Papa sat on the same seat facing the rear. The rest of us sat on the bench in the rear with Karol. We are more comfortable now, I thought.

When the traffic thinned out, Chmielinski pulled the wagon off the road so the horses could feed. He hung bags filled with oats on their necks and spread hay on the ground. Then the family shared what they had with us—home-baked bread, butter, and milk—with a hospitality that was easy to accept.

The Polish soldiers that passed us along the road didn’t resemble an army anymore. “Where are the Germans?” we asked.

“Keep going, keep going,” they replied. Although it was getting dark, we took their advice. Chmielinski set the horses off at a brisk trot. With fewer army vehicles crowding the road, we made better time.

Karol was a good-humored young man of twenty-seven who had been studying at Jagiello University in Kraków. He liked to talk about Marxism, pacifism, and Hitler. The falling dusk and the rhythmic sway of the wagon made me drowsy, and before long I was sound asleep.

It didn’t seem that I had slept long when I awoke to a familiar sound. I looked to the west and saw two dots on the horizon. The roar grew louder, and the dots grew bigger, until I could see the much-feared Messerschmitt. Chmielinski turned the wagon into a field that had already been harvested, and we climbed out. People ran, frenzied, slipping, staggering, desperate, but there was no place to hide. The roar was deafening as two bombers, side by side, circled above us. Suddenly I heard the bombs whistle. I dropped to the ground. The explosion sent earth flying, leaving huge craters behind. Terrified by the noise, the horses, sniffing blood and the odor of death, rose up on their hind legs. Although we were civilians and there was nothing military in sight, the Germans kept blasting their machine guns.

Читать дальше