As Francus read our names aloud, we responded with “Jawohl.” At 9:00 A.M. the gates of the school yard opened, and in groups of about fifty-six per truck, we boarded the three trucks. The SS guards jumped on the tailgates for one more check. With this they cast a net around us.

As we picked up speed on the cobbled streets, we saw in a doorway two women watching the approaching trucks. We got closer, and Papa and I recognized Mama and Pola. They timidly covered their yellow Star of David patches and waved to us as we passed. We stared back, our hearts as heavy as the dark clouds above, until they were no longer visible. From this moment on, our family was split apart forever.

So there we were, 167 Jewish men, sixteen to sixty years old, one, two, and in some cases even three from one family, of varied skills, lifestyles, and backgrounds. We were united in the same fate and bound together on a journey as alien to us as the times we were now in. I glanced at my father, and I saw the once-proud head of our family embarrassingly helpless.

Leaning against the side of the truck, I stared at its plume of dark exhaust, believing I saw in it my own black future. To find a bit of solace, I thought back to my childhood days.

CHAPTER II

A Small Shtetl in Poland

I was launched into the sea of life in Dobra, a small village of Western Poland, on a cold November day in 1919. According to tradition, I was named Berek, after my deceased maternal grandmother, Baila. In retrospect, I see that I was born at the wrong time, in the wrong place, and with the wrong religion to see my youthful dreams fulfilled.

With my brother, Josek, and my sister, Pola, I grew to adulthood in Dobra, where my ancestors, as far as I can tell, had lived ever since Jews settled in Poland. Our family owned a house with two and a half hectares of land that my parents had bought after they married. Ours was a modest house, even by the standard of those days. We had two bedrooms, a dining and living room, and a kitchen. A coal-fired oven, two meters tall, covered with brown ceramic tile, provided heat to our living and dining room in the winter. A black iron cookstove stood in the kitchen. Behind the house, the yard held a straw-roofed barn, two stables, and a small chicken coop. Behind that were several fruit trees. One dwarf tree bore the sweetest yellow cherries, but the sparrows always got them before we did. Plum, pear, and apple trees also flourished there. The sickle pear tree was always the last to bear fruit. On the rest of the land we grew enough rye, wheat, and potatoes to last us for the entire winter season. We worked our farmland, rising every morning at dawn to begin the daily task of plowing, sowing, and reaping crops. We were not rich. In our nonmaterialistic world we did not have much and did not want much. But we were comfortable and happy.

The only luxury I recall in our house was a colorful Oriental rug under the dining table, which was embroidered with a castle and kings. There, in my young years I lay for hours, reading adventure books or listening to music on my crystal radio set. Our dining and living room walls were covered with family portraits, pictures of men with long gray beards and women in traditional lace dresses—our ancestors.

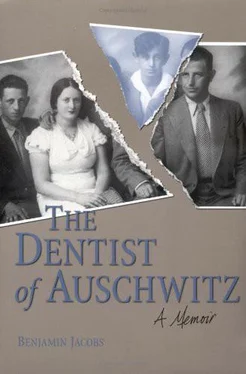

Papa owned and operated a modest grain business in which we all helped. At the age of ten I carried hundred-kilo sacks of grain on my back from the warehouse to the scale. My father was a simple, hard-working man, good-natured and utterly devoted to his family. He was short—shorter than my mother—and almost totally bald. His face was round, and his cheeks rosy. When he smiled, he expressed a kind nature. I recall that Papa had been very heavy, but once a doctor diagnosed him as having an enlarged heart, he slimmed down. He and his eight brothers and sisters were orphaned when he was only eleven. After that he moved into my maternal grandfather’s house, where he met my mother. Although they shared the same last name, Jakubowicz, they were not related. Since Papa had to work at an early age, he did not attend school and barely knew how to read or write. His signature was three crosses, but it was valid everywhere in town. My parents were married in 1912, when Papa was eighteen and Mama was sixteen. My parents rarely argued. Any disharmony that arose resulted from my father’s thrift clashing with my mother’s generosity. But an argument was as far as it ever got.

Mama was the most progressive Jewish woman in the village, the first to stop wearing the traditional wig. A mild case of diabetes kept her slim. She had dark, wavy hair and was tanned from her outdoor work. She was blessed with a heart of gold, and the poor knew on whose door to knock. The blind man, Itzchak, visited us at least once a week and was assured that he wouldn’t leave our house hungry. With a spool of wire and a cane and a bow for a musical instrument, he played songs any trained musician could envy. He imitated all the parts of the orchestra on that ersatz instrument. Mother even gave the wandering gypsies something when they came begging.

We children were never physically disciplined. Denying us meals and keeping us indoors, beyond our patience, was enough. Mama was a parent any growing child would want to have. She had complete authority over the household, although the kitchen was the responsibility of my paternal cousin Toba. We loved both our parents, not out of fear, but for the love and kindness they gave us. We were raised with devotion to Jewish tradition and with a firm belief in God.

My sister, Pola, was two years older than I. She was bright, intelligent and as tall as Mama. She wore her brown hair in a bob over her slightly elongated face. Except for lipstick, she rarely wore makeup. Her hazel eyes, with thick lashes and nicely shaped brows, accented her good looks. My brother, Josek, was six years older than I. After his Bar Mitzvah, he began the study of the Talmud. But the considerable yeshiva rigor soon proved too much for him, and he left the yeshiva and became a dental technician.

The best times of our childhood were the summers, when we went to a tiny cottage my father rented in Linne. It lay in the midst of a forest full of wild berries and mushrooms. In the mornings we set out to explore the small river, abundant with kielbiki, a small chublike fish that we would catch in round nets.

One early spring when I was barely seven, Mama gave me a small patch of land the size of the barn. “This is going to be yours,” she said. This was my special piece of land, and receiving it was a very proud moment in my young life. Since lots of wildflowers already grew nearby, I planted vegetables in my garden.

Since my mother’s mother died before I was born, her father lived with us. He was tall and slender and wore a neatly shaped goatee. He walked erect with a slight forward thrust and a rhythmic motion. He used a cane with a silver handle, not merely for support but as an expression of good taste. He loved all three of us children, but I always felt that he had special affection for me, his youngest grandson. He played a decisive role in shaping my early life. Grandpa was an expert fisherman. On warm days he would take me to the river, and in time I too could land the big ones.

Many summer days, when I came home from heder, I would find Grandpa sitting on a bench, his skullcap on, bent over and reading the Scriptures. Sometimes his eyes closed involuntarily, and he would doze off in the glow of the sun. Hearing me, he would awaken, and his mustache would turn up in a happy smile. In those days people over sixty were considered old. They usually had lined faces and toothless mouths. Our grandpa, though, had all his teeth and still read without glasses.

At times he would wait for me, prepared with two rods, a net, and a bundle under his arm, ready to take me for a fifteen-minute walk from our house, to a small tributary of the Warta River. It was so small it didn’t even have a name. As my grandfather raised his trouser legs above his calves and waded into the water, his body looked much thinner. I followed him, and he watched me bait my hook. His arms lifted as he swung the line into wide circles, until the bait fell just where he wanted it. “Slowly, Berele,” he would say, “slowly,” seeing me wrestle with my line. He knew I could do it right and wouldn’t settle for bad casts. I followed closely as the pebbles dug into the soles of my feet. When we fished with a hand net, like one used to catch butterflies, we moved in tandem, pushing the net quietly under the lily pads. “Reach deep, move slowly, step in rhythm,” he would say. No catch went to waste. Perch were made into meals, and Mama used the pickerel for gefilte fish.

Читать дальше