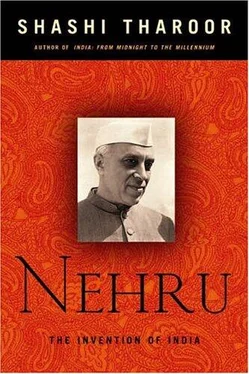

Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The massacre made Indians out of millions of people who had not thought consciously of their political identity before that grim Sunday. It turned loyalists into nationalists and constitutionalists into agitators, led the Nobel Prize — winning poet Rabindranath Tagore to return his knighthood to the king and a host of Indian appointees to British offices to turn in their commissions. And above all it entrenched in Mahatma Gandhi a firm and unshakable faith in the moral righteousness of the cause of Indian independence. He now saw freedom as indivisible from Truth (itself a concept he imbued with greater meaning than can be found in any dictionary), and he never wavered in his commitment to ridding India of an empire he saw as irremediably evil, even satanic.

While the official commission of inquiry largely whitewashed Dyer’s conduct, Motilal Nehru was appointed by the Congress to head a public inquiry into the atrocity, and he sent his son to Amritsar to look into the facts. Jawaharlal’s diary meticulously records his findings; at one point he counted sixty-seven bullet marks on one part of a wall. He visited the lane where Indians had been ordered by the British to crawl on their bellies and pointed out in the press that the crawling had not even been on hands and knees but fully on the ground, in “the manner of snakes and worms.” On his return journey to Delhi by train he found himself sharing a compartment with Dyer and a group of British military officers. Dyer boasted, in Nehru’s own account, that “he had [had] the whole town at his mercy and he had felt like reducing the rebellious city to a heap of ashes, but he took pity on it and refrained. . I was greatly shocked to hear his conversation and to observe his callous manner.”

The son’s investigations drew him even closer politically to his father. Motilal was elected president of the Congress session of 1919, which took place, deliberately, in Amritsar. The massacre dispelled some of his doubts about Gandhi’s doctrine of noncooperation; henceforward he joined his son in accepting that the British had left little room for an alternative. For Jawaharlal, the English reaction to the massacre — Dyer was publicly feted, and a collection raised for him among English expatriates in India brought him the quite stupendous sum of a quarter of a million pounds — was almost as bad as the massacre itself. “This cold-blooded approval of that deed shocked me greatly,” he later wrote. “It seemed absolutely immoral, indecent; to use public school language, it was the height of bad form. I realized then, more vividly than I had ever done before, how brutal and immoral imperialism was and how it had eaten into the souls of the British upper classes.”

In early 1920 Mahatma Gandhi embarked on the Khilafat movement, which rallied Hindus and Muslims together on the somewhat obscure platform of demanding the restoration of the Caliphate in Turkey. Gandhi did not particularly want a religious figurehead to take over the dissolving Ottoman Empire in preference to a secularizing figure (such as later emerged in the person of Kemal Ataturk), but he saw that the issue mattered to several Indian Muslim leaders and he wished to seize the opportunity to consolidate the Hindu-Muslim unity that had emerged over the previous four years. Jawaharlal’s secular instincts would ordinarily have put him on the opposite side of this issue, but he saw the political merits of the movement and wrote articles in the Independent depicting the Khilafat movement as an integral part of the ongoing political struggle for Asia’s freedom. The agitation briefly inspired the masses, many of whom had no real idea where Turkey was or why the Khilafat mattered. It also brought anti-British Muslims into the Congress, since many Muslim Leaguers were allied with the government and unwilling to oppose it for the sake of the caliph. But as a modernizing Turkey itself turned away from the cause, it petered out as a significant issue in Indian politics.

Meanwhile, the death of Tilak and the official launching of Gandhi’s noncooperation movement, both on August 1, 1920, marked the Mahatma’s ascension to unchallenged leadership of the Indian National Congress. (Gokhale had died earlier, in 1915, at the shockingly young age of forty-nine.) The special session of the Congress in Calcutta that year saw the entire old guard of the party arrayed against Gandhi, but as the debates progressed and the Mahatma clung stubbornly to the dictates of his conscience, the leadership realized they needed him more than he needed them. Gandhi’s program passed in committee with strong Muslim support and the surprising defection from the old guard of Motilal Nehru; it was then resoundingly adopted by the plenary. This was a defeat, above all, for Jinnah, the principal epitome of the old “drawingroom” politics, who wrote to the Mahatma to deplore his appeal to “the inexperienced youth and the ignorant and the illiterate. All this means complete disorganization and chaos. What the consequences of this may be, I shudder to contemplate.” His disillusionment with Gandhi’s mass mobilization led to Jinnah’s gradual withdrawal from political life — booed off the stage at the 1920 Nagpur Congress, he took the next train to Delhi, never to return to the party — and later, in 1930, to bitter, if comfortable, self-exile in England. When he returned, it would be to challenge everything that Gandhi stood for.

But Jawaharlal was thrilled by the Mahatma’s triumph. Some have suggested that Motilal’s shift to the pro-Gandhi side at Calcutta was prompted by his regard for his son, whose affections he feared he would otherwise have lost. The Khilafat movement and noncooperation prompted Jawaharlal also to follow Gandhi’s call to boycott the legislative councils for which elections were to be held under the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms. Motilal had been leading the Congress’s election effort in the province and only reluctantly acquiesced in the party’s decision — which his son had strongly urged — to boycott the elections. Jawaharlal was soon a leading figure in the United Provinces (U.P.) 4noncooperation movement, organizing drills for volunteers and casting aside his diffidence to address large crowds. His message was simple: “there was no middle course left; one was with either the country or its enemies, either with Gandhi or the Government.” His first direct clash with the government occurred in May 1920 when he was on holiday with his family in Mussoorie and was asked by the police to provide an undertaking not to contact an Afghan delegation which was staying at the same hotel. Though Jawaharlal had had no intention of meeting the Afghans — whom the British suspected of being in India to lend support to the Khilafat movement — he refused to furnish such an undertaking, and was duly externed from Mussoorie. Jawaharlal accepted his expulsion; for all his admiration for the Mahatma, he was not yet politician enough, or Gandhian enough, to defy the police and court arrest — much to the relief of Motilal, who feared the consequences to the family of such an action.

These were difficult times for Motilal. He had given up his legal practice at the peak of his career to devote himself to politics, but it saddened him to see his son, in his prime, embracing Gandhian austerity and traveling in third-class railway carriages. The loss of a steady income from what had been a flourishing practice meant that the comforts of life were being denied his family. (Some of this was by choice: the closing of the wine cellar, the exchange of the Savile Row suits for homespun khadi, the replacement of three English meals a day by one simple Indian lunch.)

Jawaharlal’s daughter, Indira Priyadarshini, was born on November 19, 1917, but was receiving little attention from her increasingly politically active father. (Her admirably simple first name, though, was something Jawaharlal may well have insisted upon. He had never liked his own polysyllabic and traditional appellation, once writing to a friend: “for heaven’s sake don’t call your son Jawaharlal. Jawahar [ jewel ] by itself might pass, but the addition of ‘lal’ [ precious ] makes it odious.”) Childbirth at eighteen left Kamala weak and ill, and her husband’s neglect could not have improved matters for her. On one occasion Jawaharlal failed to decipher a prescription the Nehru family homeopath had written for his wife, and Motilal snapped: “There is nothing very complicated about Dr. Ray’s letter if you will only read it carefully after divesting your mind of Khilafat and Satyagraha.” Jawaharlal was, typically, blissfully unconscious of the financial burdens his own father had to bear, cheerfully donating to the Congress cause the war bonds Motilal had put aside for his inheritance. Motilal finally closed the Independent in 1921, unable to sustain its continuing losses. Too proud to draw a salary for his political work, Motilal decided to resume his legal practice so that his family would be provided for. Jawaharlal, enthralled by Gandhian self-denial, cared little about such matters, provoking his father to declare bluntly: “You cannot have it both ways: Insist on my having no money and yet expect me to pay you money.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.