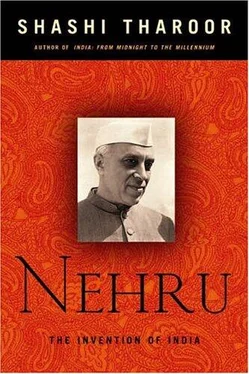

Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was not to last. The increasing violence of the noncooperation movement, and in particular the murder of two dozen policemen by a nationalist mob in the small U.P. town of Chauri Chaura on February 5, 1922, led Mahatma Gandhi to call off the agitation, fearing that his followers were not yet ready for the nonviolent attainment of freedom. Thanks to a technical error in his sentencing, Jawaharlal was released in March 1922, with only half his sentence served. He was bitterly disappointed with Gandhi’s decision and its effect on his volunteers, who had made such headway in destabilizing British rule in U.P. But his faith in the Mahatma remained, and he wrote to his colleague Syed Mahmud: “You will be glad to learn that work is flourishing. We are laying sure foundations this time. … [T]here will be no relaxation, no lessening in our activities and above all there will be no false compromise with Government. We stand,” he added in a Gandhian touch, “for the truth.”

It is said that Motilal enjoyed such close relations with the British governor of U.P., Sir Harcourt Butler, that during his first imprisonment he received a daily half-bottle of champagne brought personally to the prison by the governor’s aide-de-camp. With his father still in jail, Jawaharlal continued his efforts to promote disaffection with British rule, and for his pains he was arrested again on May 12, 1922. Refusing to defend himself, he issued an emotional and colorful statement: “India will be free; of that there is no doubt. … Jail has indeed become a heaven for us, a holy place of pilgrimage since our saintly and beloved leader was sentenced. … I marvel at my good fortune. To serve India in the battle of freedom is honor enough. To serve her under a leader like Mahatma Gandhi is doubly fortunate. But to suffer for the dear country! What greater good fortune could befall an Indian, unless it be death for the cause or the full realization of our glorious dream?”

The British may have dismissed such words as romanticized bombast, but they struck a chord among the public beyond the courtroom, giving the thirty-three-year-old Jawaharlal Nehru national celebrity as the hero of Indian youth. The trial court was his platform, but his real audience was young Indians everywhere. By the summer of 1922, Motilal, now released and traveling across the country, found his son’s fame widespread, and his already considerable pride in Jawaharlal grew even further. “On reading your statement,” he wrote to his son, “I felt I was the proudest father in the world.” This time the younger Nehru drew a sentence of eighteen months’ rigorous imprisonment, a fine of a hundred rupees, and a further three months in jail if he did not pay the fine. There were no judicial irregularities to mitigate his punishment.

Despite poor health, which required homeopathic medication in jail, and food that was “quite amazingly bad,” Jawaharlal welcomed his imprisonment. He seemed to see it as confirmation of his sacrifices for the nation, while writing to his father that no sympathy was needed for “we who laze and eat and sleep” while others “work and labor outside.” He used his time to read widely — the Koran, the Bible, and the Bhagavad Gita, a history of the Holy Roman Empire, Havell’s Aryan Rule in India with its paeans to India’s glorious past, and the memoirs of the Mughal emperor Babar and the French traveler Bernier. These works fed a romanticized sense of the Indian nationalist struggle as a version of the Italian Risorgimento; in one letter he even quoted Meredith’s poem on the heroes of the latter, substituting the word “India” for “Italia.” This, as Gopal has observed, “was adolescent exaltation, yet to be channeled by hard thinking.” Jawaharlal was suffused with “the glow of virginal suffering, … in love with sacrifice and hardship. … He had made a cradle of emotional nationalism and rocked himself in it.” A British interviewer in late 1923 noted that Nehru had no “clear idea of how he proposed to win Swaraj or what he proposed to do with it when he had won it.”

Once again Jawaharlal was released before he had served his full sentence, emerging from prison at the end of January 1923 following a provincial amnesty. But the premature release would be more than made up for in seven more terms of imprisonment over the next two decades, which gave him a grand total of 3,262 days in eight different jails. Nearly ten years of his life were to be wasted behind bars — though perhaps not entirely wasted, since they allowed him to produce several remarkable books of reflection, nationalist awakening, and autobiography. His first letter to his five-year-old daughter Indira (asking her whether she had “plied” her new spinning wheel yet) was written from Lucknow jail. This largely one-sided correspondence would later culminate in two monumental books painting a vivid portrait of Jawaharlal Nehru’s mind and of his vision of the world.

In the meantime, the early 1920s found Indian nationalism in the doldrums. Gandhi’s decision to call off the noncooperation movement was baffling to many Muslim leaders, who saw in his placing the principle of nonviolence above the exigencies of opposition to British rule a form of Hindu religious fervor that sat ill with them. This, and the fizzling out of the Khilafat movement, ended what had been the apogee of Hindu-Muslim unity in Indian politics, a period when the Muslim leader Maulana Muhammad Ali 5could tell the Amritsar Congress in 1919: “After the Prophet, on whom be peace, I consider it my duty to carry out the demands of Gandhiji.” The president of the Muslim League in 1920, Dr. M. A. Ansari, had abandoned the League for the Congress; the Congress’s own president in 1921, Hakim Ajmal Khan, had been a member of the original delegation of Muslim notables to the viceroy in 1906 which had first established the League. Yet by 1923 a growing estrangement between the two communities became apparent, with several Hindu-Muslim riots breaking out, notably the “Kohat killings” and the “Moplah rebellion” in opposite extremities of the country. In the twenty-two years after 1900 there had been only sixteen communal riots throughout India; in the three years thereafter, there were seventy-two. The Mahatma responded by undertaking fasts to shame his countrymen into better behavior.

During this time Jawaharlal found his leader unwilling to lead. Gandhi “refused to look into the future, or lay down any long-distance program. We were to carry on patiently ‘serving’ the people.” This, despite the ironic quotation marks around the word “serving,” Jawaharlal continued to do, focusing particularly on the boycott of foreign cloth and the promotion of homespun, a cause which bolstered Indian self-reliance while uniting peasants, weavers, and political workers under a common Congress banner. But he was too dispirited to do more than extol khadi; in particular, he took no specific steps to combat the growing communalization of politics. Devoid of religious passions himself, with many close Muslim friends whom he saw as friends first and Muslims after (if at all), he could not at this time take religious divisions seriously; he saw them as a waste of time, a distraction from the real issues at hand. “Senseless and criminal bigotry,” he wrote in a speech delivered for him when he was ill in October 1923, “struts about in the name of religion and instills hatred and violence into the people.” Three years later he wrote to a Muslim friend that “what is required in India most is a course of study of Bertrand Russell’s books.” The atheist rationalism of the British philosopher was to remain a profound influence; religion, Nehru wrote, was a “terrible burden” that India had to get rid of if it was to “breathe freely or do anything useful.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.