JUDITH FLANDERS

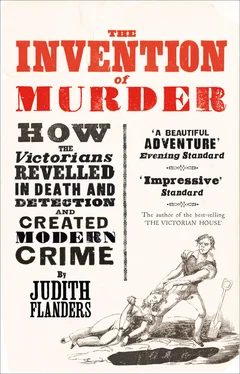

The Invention of Murder

How the Victorians Revelled in Death and

Detection and Invented Modern Crime

For Susan and Ellen without whom …

Cover

Title Page JUDITH FLANDERS The Invention of Murder How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Invented Modern Crime

TEXT ILLUSTRATIONS

A NOTE ON CURRENCY

ONE Imagining Murder

TWO Trial by Newspaper

THREE Entertaining Murder

FOUR Policing Murder

FIVE Panic

SIX Middle-Class Poisoners

SEVEN Science, Technology and the Law

EIGHT Violence

NINE Modernity

NOTES

SOURCES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

‘The funeral of the murdered Mr. and Mrs. Marr and infant son’, broadside of c.1811. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection/JJ Crime 10[13])

‘The public Exhibition of the Body of Williams’, from The New Newgate Calendar, Vol. V by Andrew Knapp and William Baldwin, c.1826.

‘The pond in the garden, into which Mr. Weare was first thrown’, from Pierce Egan’s Account of the Trial of John Thurtell and Joseph Hunt, 1824.

‘Execution of William Corder at Bury, August 11 1828’, from An Authentic and Faithful History of the Mysterious Murder of Maria Marten by J. Curtis, 1828.

‘Elegiac Lines on the Tragical Murder of Poor Daft Jamie’, broadside of 1829. (National Library of Scotland, Ry.III.a.6[017])

‘New’ policeman, from a song-sheet c.1830. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

‘Apprehension of the Murderer of the Female whose Body was found in the Edgware Road in December last’, broadside of 1837. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection/JJ Broadsides: Murder & Executions Folder 6[5])

‘Two sudden blows with a ragged stick and one with a heavy one’, illustration by William Harvey for ‘The Dream of Eugene Aram, The Murderer’ by Thomas Hood, 1831.

Playbill for Jim Myers’ Great American Circus at the Pavilion Theatre, June 1859, including Turpin’s Ride to York, or, The Death of Bonny Black Bess. (Theatre & Performance Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum, London/© V&A Images)

‘“Parties” for the gallows’, Punch cartoon, 1845.

‘Interior of the court-house, during the trial of Rush – examination of Eliza Chestney’, from the Illustrated London News, 7 April 1849. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

‘See, dear, what a sweet doll Ma-a has made for me’, Punch cartoon, 1850.

‘Madame Tussaud her wax werkes: ye Chamber of Horrors!!’, Punch cartoon, 1849.

‘Execution of the Mannings’, broadside of 1849. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection/JJ Crime 2[5])

‘The Telegraph Office’, from The Progress of Crime: or, Authentic Memoirs of Marie Manning by Robert Huish, 1849. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011)

‘Awful Murder of Lord William Russell, MP’, broadside of 1840. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection/JJ Broadsides: Murder & Executions Folder 10[29])

Advertisement for Dr. Mackenzie’s Arsenical Toilet Soap, 1898.

‘Sarah Chesham’s Lamentation’, broadside of c.1851. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: Firth c.17[261]) ‘Fatal facility; or, Poisons for the asking’, Punch cartoon, 1849. Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, self-portrait, from Janus Weathercock by Jonathan Curling, 1938.

‘Drs. Taylor and Rees performing their analysis’, from Illustrated and unabridged edition of the Times report of the trial of W. Palmer for poisoning J.P. Cook, 1856. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011)

‘The Life, Confession and Execution of Mrs. Burdock’, broadside of 1835. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011)

‘Copy of Verses on the Awful Murder of Sara Hart’, broadside of 1845. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011) Execution of Henry Wainwright, from Supplement to the Illustrated Police News, 21 December 1875. (Guildhall Library, City of London/The Bridgeman Art Library)

William Terriss and W.L. Abingdon in The Fatal Card, 1894. (Theatre & Performance Collection, Victoria & Albert Museum, London/© V&A Images)

‘Murder and mutilation of the body’, from The Alton Murder! The Police News edition of the life and examination of Frederick Baker, 1867. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011)

‘“Scott”, alias E. Sweeney, of Ardlamont mystery fame’, from the Graphic, 14 April 1849. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Portrait of Mary Eleanor Wheeler (alias Pearcey), pencil, pen and ink drawing by Sir Leslie Ward, 1890. (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

‘Removing Lipski from under the bed’, from the Illustrated Police News, 9 July 1887.

‘Horrible London; or, The pandemonium of posters’, Punch cartoon, 1888.

‘With the Vigilance Committee in the East End’, from the Illustrated London News, 13 October 1888. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Advertisement for ‘The Great Surprise Watch’ from M.J. Haynes & Co.’s Specialities,1889. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011)

Pounds, shillings and pence were the divisions of British currency in the nineteenth century. One shilling was made up of twelve pence; one pound of twenty shillings, i.e. 240 pence. Pounds were represented by the £ symbol, shillings as ‘s.’, and pence as ‘d.’ (from the Latin denarius). ‘One pound, one shilling and one penny’ was written as £1.1.1. ‘One shilling and sixpence’, referred to in speech as ‘One and six’, was written as 1s.6d., or ‘1/6’.

A guinea was a coin to the value of £1.1.0 (the coin was not circulated after 1813, although the term remained and tended to be reserved for luxury goods). A sovereign was a twenty-shilling coin, a half-sovereign a ten-shilling coin. A crown was five shillings, half a crown 2/6, and the remaining coins were a florin (two shillings), sixpence, a groat (four pence), a threepenny bit (pronounced ‘thrup’ny’), twopence (pronounced ‘tuppence’), a penny, a halfpenny (pronounced hayp’ny), a farthing (a quarter of a penny) and a half a farthing (an eighth of a penny).

Relative values have altered so substantially that attempts to convert nineteenth-century prices into contemporary ones are usually futile. However, the website http://www.ex.ac.uk/~RDavies/arian/current/howmuch.html is a gateway to this complicated subject.

‘We are a trading community – a commercial people. Murder is, doubtless, a very shocking offence; nevertheless, as what is done is not to be undone, let us make our money out of it.’

‘Blood’, Punch, 1842

‘Pleasant it is, no doubt, to drink tea with your sweetheart, but most disagreeable to find her bubbling in the tea-urn.’ So wrote Thomas de Quincey in 1826, and indeed, it is hard to argue with him. But even more pleasant, he thought, was to read about someone else’s sweetheart bubbling in the tea urn, and that, too, is hard to argue with, for crime, especially murder, is very pleasant to think about in the abstract: it is like hearing blustery rain on the windowpane when sitting indoors. It reinforces a sense of safety, even of pleasure, to know that murder is possible, just not here. At the start of the nineteenth century, it was easy to think of murder that way. Capital convictions in the London area, including all the outlying villages, were running at a rate of one a year. In all of England and Wales in 1810, just fifteen people were convicted of murder out of a population of nearly ten million: 0.15 per 100,000 people. (For comparison purposes, in Canada in 2007–08 the homicide rate was 0.5 per 100,000 people, in the EU, 1.8 per 100,000, in the USA 2.79, while Moscow averaged 9.6 and Cape Town 62 per 100,000.)

Читать дальше