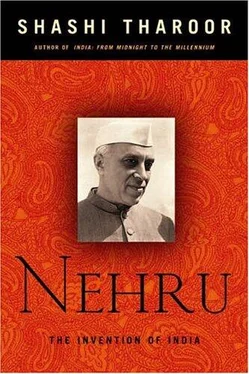

Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Motilal also generously funded his spendthrift son, rewarding him handsomely for every educational attainment, however modest. Every time he bridled at his son’s profligacy, Jawaharlal managed to win him round. (On one such occasion Motilal wrote: “You know as well as anyone else does that, whatever my shortcomings may be, and I know there are many, I cannot be guilty of either love of money or want of love for you.”) It was one of Motilal’s lavish gifts — a graduation present of a hundred pounds — that nearly ended Jawaharlal Nehru’s career. Urged by Motilal to spend the money visiting France and learning the language, Jawaharlal chose instead to go trekking in the Norwegian mountains with an unnamed English friend. Dipping into a stream, the young Nehru, numbed by the icy water, was swept away by a current toward a steep waterfall and would have drowned but for the pluck and enterprise of his traveling companion, who ran along the riverbank and caught him just in time, grasping a flailing leg and pulling him out of the water a few yards ahead of a four-hundred-foot drop.

This episode led a recent biographer, the American historian Stanley Wolpert, to suggest that Jawaharlal Nehru had had a homosexual relationship with his savior. Wolpert’s conclusions are based, however, on so elaborate a drawing out of the circumstances, and such extensive speculation (on grounds as flimsy as Jawaharlal’s tutor Brooks having been a disciple of a notorious pederast), that they are difficult to take seriously. Certainly there is no corroborating evidence, either in letters or the accounts of contemporaries, to substantiate Wolpert’s claim of homosexuality. It was quite common in those days for young men to travel in pairs on the Continent, and difficult to imagine that friends, family, and acquaintances would have made no reference to homosexual tendencies if Jawaharlal had indeed been inclined that way. Nor did any chroniclers of the adult Nehru, including enemies who would have used such a charge to wound him, ever allude to any rumors of adolescent homosexuality.

By the time he embarked for India in August 1912 after nearly seven years in England, Jawaharlal Nehru had little to show for the experience: he was, in his own words, “a bit of a prig with little to commend me.” Had he been better at taking exams, he might well have followed his father’s initial wishes and joined the Indian Civil Service, but his modest level of academic achievement made it clear he stood no chance of succeeding in the demanding ICS examinations. Had he joined the ICS, a career in the upper reaches of the civil service might have followed, rather than in the political fray. Officials did not become statesmen; it is one of the ironies of history that had Jawaharlal Nehru been a higher achiever in his youth, he might never have attained the political heights he did in adulthood.

But there had certainly been an intangible change in the young man, for all the modesty of his scholarly accomplishment. In a moving letter upon leaving his son at Harrow, Motilal had described his pain in being separated from “the dearest treasure we have in this world … for your own good”:

It is not a question of providing for you, as I can do that perhaps in one single year’s income. It is a question of making a real man of you. … It would be extremely selfish … to keep you with us and leave you a fortune in gold with little or no education.

Seven years later, the son confirmed that he had understood and fulfilled his father’s intent. “To my mind,” Jawaharlal wrote to his father four months before leaving England, in April 1912, “education does not consist of passing examinations or knowing English or mathematics. It is a mental state.” In his case this was the mental state of an educated Englishman of culture and means, a product of two of the finest institutions of learning in the Empire (the same two, he would later note with pride, that had produced Lord Byron), with the attitudes that such institutions instill in their alumnae. Jawaharlal Nehru may only have had a second-class degree, but in this sense he had had a first-class English education.

The foundations had been laid, however unwittingly, for the future nationalist leader. It would hardly be surprising that Jawaharlal Nehru, having imbibed a sense of the rights of Englishmen, would one day be outraged by the realization that these rights could not be his because he was not English enough to enjoy them under British rule in India.

2.“Greatness Is Being Thrust upon Me”: 1912–1921

The return home of the not-quite-prodigal, not-yet-prodigious Jawaharlal Nehru, B.A. (Cantab.), LL.B., was a major occasion for the Nehru family. When he stepped off the boat in Bombay, he was greeted by a relative; the family, with a retinue of some four dozen servants, awaited him at the hill station of Mussoorie, where his ailing mother had gone to escape the heat of the plains. Jawaharlal took a train to Dehra Dun, where he alighted into the warm embrace of a visibly moved Motilal. Both father and son then rode up to the huge mansion Motilal had rented for the occasion, and there was, if accounts of the moment are to be believed, something improbably heroic about the dashing young man cantering up the drive to reclaim his destiny. The excited women and girls rushed outside to greet him. Leaping out of the saddle and flinging the reins to a groom, Jawaharlal scarcely paused for breath as he ran to hug his mother, literally sweeping her off her feet in his joy. He was home.

He was soon put to work in his father’s chambers, where his first fee as a young lawyer was the then princely sum of five hundred rupees, offered by one of Motilal’s regular clients, the wealthy Rao Maharajsingh. “The first fee your father got,” Motilal noted wryly, “was Rs. 5 (five only). You are evidently a hundred times better than your father.” The older man must have understood perfectly well that his client’s gesture was aimed at Motilal himself; his pride in his son was well enough known that people assumed that kindness to the as yet untested son was a sure way to the father’s heart. As he had done at Harrow, Jawaharlal worked hard at his briefs, but his confidence faltered when he had to argue his cases in court, and he was not considered much of a success. It did not help that his interest in the law was at best tepid and that he found much of the work assigned to him “pointless and futile,” his cases “petty and rather dull.”

Jawaharlal sought to escape the tedium of his days by partying extravagantly at night, a habit encouraged by his father’s own penchant for lavish entertainment. He called on assorted members of Allahabad’s high society, leaving his card at various English homes. But he made no great mark upon what even his authorized biographer called “the vacuous, parasitic life of upper-middle-class society in Allahabad.” At his own home, Jawaharlal played the role of the dominant elder brother. He tormented his little sister Betty, startling her horse to teach her to hold her nerve, or throwing her into the deep end of the pool to force her to learn to swim. These lessons served more to instill fear than courage in the little girl. He took holidays in Kashmir, on one occasion going on a hunt and shooting an antelope that died at his feet, its “great big eyes full of tears” — a sight that would haunt Jawaharlal for years.

All told, however, there was little of note about Jawaharlal Nehru’s first few years back in India, until his marriage — arranged, of course, by his father — in February 1916. Father and son had dealt with the subject of marriage in their transcontinental correspondence, but Motilal had given short shrift to Jawaharlal’s mild demurrals whenever the matter was broached. In a letter to his mother Jawaharlal had even suggested he might prefer to remain unmarried rather than plight his troth to someone he did not like: “I accept that any girl selected by you and father would be good in all respects, but still, I may not be able to get along well with her.” But for all the romantic idealism in his epistolary descriptions of the ideal marriage, he gave in to his parents’ wishes. For his parents, there was no question of allowing the young man to choose his own bride; quite apart from the traditional practice of arranging marriages, Motilal took a particular interest in seeing that his son was well settled. “It is all right, my boy,” he wrote to Jawaharlal as early as 1907 on the subject. “You may leave your future happiness in my hands and rest assured that to secure that is the one object of my ambition.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.