Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

One other political movement deserves mention. Hindutva, literally “Hinduness,” is the cause advanced by Hindu zealots who harken back to atavistic pride in India’s Hindu heritage and seek to replace the country’s secular institutions with a Hindu state. Their forebears during the nationalist struggle were the Hindu Mahasabha, a party advancing Hindu communal interests neglected by the secular Congress, and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh(RSS), or National Volunteer Corps, modeled on the Italian Brown Shirts. Neither found much traction within the Congress, and the Hindu Mahasabha faded away, but the creation of Pakistan and the terrible communal bloodletting that accompanied partition provided Hindu zealots new sources of support. The Bharatiya Jana Sangh, or Indian People’s Party, was founded after independence as the principal vehicle for their political aspirations. The Sangh merged into the short-lived omnibus party, the Janata, in 1977, and reemerged in 1980 as the Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP. Today the principal votaries of Hindutva are a “family” of organizations collectively known as the Sangh Parivar, including the RSS, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (World Hindu Council), the Bajrang Dal, and a large portion of the Bharatiya Janata Party, which since 1998 heads a coalition government in New Delhi.

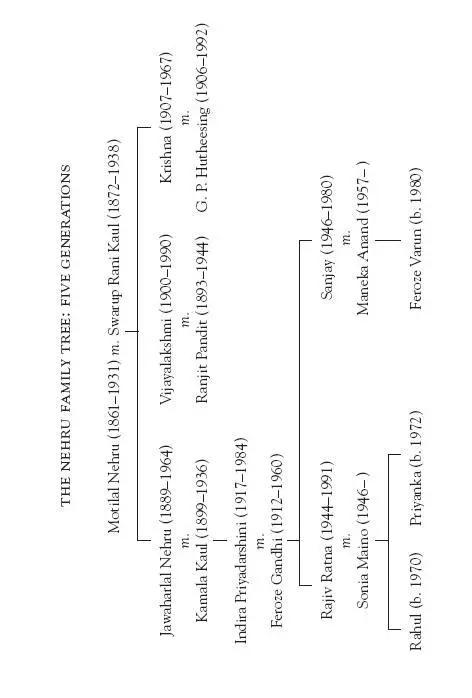

THE NEHRU FAMILY TREE: FIVE GENERATIONS

1.“With Little to Commend Me”: 1889–1912

In January 1889, or so the story goes, Motilal Nehru, a twenty-seven-year-old lawyer from the north Indian city of Allahabad, traveled to Rishikesh, a town holy to Hindus, up in the foothills of the Himalayas on the banks of the sacred river Ganga (Ganges). Motilal was weighed down by personal tragedy. Married as a teenager, in keeping with custom, he had soon been widowed, losing both his wife and his firstborn son in childbirth. In due course he had married again, an exquisitely beautiful woman named Swarup Rani Kaul. She soon blessed him with another son — but the boy died in infancy. Motilal’s own brother Nandlal Nehru then died at the age of forty-two, leaving to Motilal the care of his widow and seven children. The burden was one he was prepared to bear, but he desperately sought the compensatory joy of a son of his own. This, it seemed, was not to be.

Motilal and his two companions, young Brahmins of his acquaintance, visited a famous yogi renowned for the austerities he practiced while living in a tree. In the bitter cold of winter, the yogi undertook various penances, which, it was said, gave him great powers. One of the travelers, Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, informed the yogi that Motilal’s greatest desire in life was to have a son. The yogi asked Motilal to step forward, looked at him long and hard, and shook his head sadly: “You,” he declared, “will not have a son. It is not in your destiny.”

As a despairing Motilal stood crestfallen before him, the other man, the learned Pandit Din Dayal Shastri, argued respectfully with the yogi. The ancient Hindu shastras, he said, made it clear that there was nothing irreversible about such a fate; a great karmayogi like him could simply grant the unfortunate man a boon. Thus challenged, the yogi looked at the young men before him, and finally sighed. He reached into his brass pitcher and sprinkled water from it three times upon the wouldbe father. Motilal began to express his gratitude, but the yogi cut him short. “By doing this,” the yogi breathed, “I have sacrificed all the benefits of all the austerities I have conducted over many generations.”

The next day, as legend has it, the yogi passed away.

Ten months later, at 11:30 P.M. on November 14, 1889, Motilal Nehru’s wife, Swarup Rani, gave birth to a healthy baby boy. He was named Jawaharlal (“precious jewel”), and he would grow up to be one of the most remarkable men of the twentieth century.

Jawaharlal Nehru himself always disavowed the story as apocryphal, though it was attributed by many to two of the protagonists themselves — Motilal and Malaviya. Since neither left a firsthand account of the episode, the veracity of the tale can never be satisfactorily determined. Great men are often ascribed remarkable beginnings, and at the peak of Jawaharlal Nehru’s career there were many willing to promote a supernatural explanation for his greatness. His father, certainly, saw him from a very early age as a child of destiny, one made for extraordinary success; but as a rationalist himself, Motilal is unlikely to have based his faith in his son on a yogi’s blessing.

The child himself was slow to reveal any signs of potential greatness. He was the kind of student usually referred to as “indifferent.” He also luxuriated in the pampering of parents whose affluence grew with the mounting success of Motilal Nehru’s legal career. In a pattern well-known in traditional Indian life, where wives received very little companionship from their husbands and transferred their emotional attentions to their sons instead, Jawaharlal was smothered with affection by his mother, in whom he saw “Dresden china perfection.” Years later he would begin his autobiography with the confession: “An only son of prosperous parents is apt to be spoilt, especially so in India. And when that son happens to have been an only child for the first eleven years of his existence, there is little hope for him to escape this spoiling.”

The young Jawaharlal Nehru’s mind was shaped by two sets of parental influences that he never saw as contradictory — the traditional Hinduism of his mother and the other womenfolk of the Nehru household, and the modernist, secular cosmopolitanism of his father. The women (especially Swarup’s widowed sister Rajvati) told him tales from Hindu mythology, took him regularly to temples, and immersed him for baths in the holy river Ganga. Motilal, on the other hand, though he never disavowed the Hindu faith into which he was born, refused to undergo a “purification ceremony” in order to atone formally for having “crossed the black water” by traveling abroad, and in 1899 was formally excommunicated by the high-caste Hindu elders of Allahabad for his intransigence. The taint lingered, and Motilal’s family was socially boycotted by some of the purists, but the Nehrus typically rose above the ostracism through their own worldly success.

The Nehrus were Kashmiri Pandits, scions of a community of Brahmins from the northernmost reaches of the subcontinent who had made new lives for themselves across northern and central India since at least the eighteenth century. Kashmir itself had been largely converted to Islam in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but Kashmiri Muslims followed a syncretic version of the faith imbued with the gentle mysticism of Sufi preachers, and coexisted in harmony with their Hindu neighbors. Though the Pandits left Kashmir in significant numbers, they did so not as refugees fleeing Muslim depredation, but as educated and professionally skilled migrants in quest of better opportunities. Though the Kashmiri Pandits were as clannish a community as any in India — conscious that their origins, their modest numbers, their high social standing, and their pale, fine-featured looks all made them special — they were proud of their pan-Indian outlook. They had, after all, left their original homes behind in the place they still called their “motherland,” Kashmir; they had thrived in a state where Muslims outnumbered them thirteen to one; they had no history of casteist quarrels, since the non-Brahmin castes of Kashmir, and several of the Brahmins, had converted to Islam; they were comfortable with Muslim culture, with the Persian language, and even with the eating of meat (which most Indian Brahmins other than Kashmiris and Bengalis abjured). Secure in themselves and at ease with others, Kashmiri Pandits inclined instinctively toward the cosmopolitan. It was no accident, for instance, that Motilal’s chief household retainer was a Muslim, Munshi Mubarak Ali. Jawaharlal learned a great deal from him: “With his fine grey beard he seemed to my young eyes very ancient and full of old-time lore, and I used to snuggle up to him and listen, wide-eyed, by the hour to his innumerable stories.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.