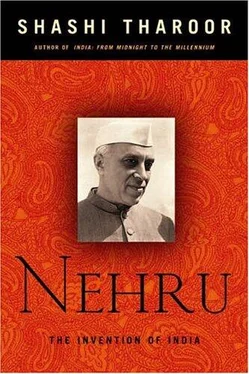

Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The family’s original name was Kaul. Jawaharlal Nehru’s ancestor Raj Kaul settled in Mughal Delhi in the eighteenth century and, perhaps because there were other Kauls of prominence in the city, assumed the hyphenated name of Kaul-Nehru, the suffix indicating the family’s residence on the edge of a canal, or nehar in Urdu. (It is also possible the name came from the village of Naru in the Badgam district of Kashmir, but this has never been conclusively established.) The Kaul-Nehrus moved to Agra in the mid-nineteenth century, where the compound form soon disappeared. It was simply as a Nehru that Motilal made his name at the Allahabad bar.

Along with the name and the money that came with his success as a lawyer, Motilal acquired the trappings of a Victorian gentleman of means — an elegant house (named Anand Bhavan, or “Abode of Bliss”) in a desirable residential area, with mostly British neighbors; a fancy carriage; a stable of Arabian steeds; and a wardrobe full of English suits, many tailored in Savile Row. Jawaharlal grew up surrounded by every imaginable creature comfort. Not only did he have electricity and running water in the house (both unheard-of luxuries for most of his compatriots), but the family home was equipped with such unusual perquisites as a private swimming pool and a tennis court, and his father ordered the latest toys for him from England, including the newly invented tricycle and bicycle. (Motilal himself owned Allahabad’s first car, imported in 1904.) Jawaharlal enjoyed lavish birthday parties, holidays in Kashmir, a plenitude of clothes — a classic Little Lord Fauntleroy upbringing.

The allusion is not too far-fetched. There is a studio photograph of Jawaharlal aged five in 1894, attired in a navy blue sailor suit, his hair neatly combed under a high stiff collar, his little hands firmly grasped between his knees, while the paterfamilias looms above, left arm cocked at his side, gold watch-chain at his waist, surveying the world with gimlet eyes above his handlebar moustache. Swarup Rani Nehru, seated to the side in an elaborate sari, seems almost marginal to this striking tableau of bourgeois Victorian male authority. (There is another photograph of mother and son: this time, Jawaharlal is in Indian clothes, and Motilal is absent.)

It was at about this time that an episode occurred that Jawaharlal would recall for decades afterward. His father had two fine pens in an inkstand atop his mahogany desk, which caught the young boy’s eye. Thinking that Motilal “could not require both at the same time,” Jawaharlal took one for his lessons. When Motilal found it missing, a furious search ensued. The frightened boy first hid the pen and then himself, but he was soon discovered by servants and turned in to his enraged father. What ensued was, in Jawaharlal’s recollection, “a tremendous thrashing. Almost blind with pain and mortification at my disgrace, I rushed to my mother, and for several days various creams and ointments were applied to my aching and quivering little body.” He learned much from this experience: not to cross his father, not to lay claim to what was not his, not to conceal evidence of his own wrongdoing, if ever he were to do wrong — and never to assume he could simply “get away with it.” It was a lesson which had much to do with the sense of responsibility that became a defining Nehru characteristic.

Motilal and Jawaharlal remained the only male Nehrus in the immediate family. A sister, Sarup Kumari (who would one day be known to the world as the glamorous Vijayalakshmi Pandit, the first woman president of the United Nations General Assembly), was born on August 18, 1900. On Jawaharlal’s sixteenth birthday, another ill-fated boy was born; he died within a month, the third of Motilal’s four sons to fail to outlive his infancy. Two years later, on November 2, 1907, the last of Jawaharlal Nehru’s siblings, another sister, Krishna, emerged. The older of the two girls was nicknamed “Nanhi,” or “little one” in Hindi, the younger “Beti,” or “daughter.” Their English governesses quickly transmuted these diminutives to “Nan” and “Betty” respectively, and it was the Anglicized versions of the nicknames that stuck, not the Hindi ones.

Indeed, Jawaharlal Nehru’s sailor suit in that early photograph was not just for posing. It embodied the Westernization of his early upbringing; he had two British governesses at home, and from 1901 to 1904 a private tutor, the Irish-French Ferdinand T. Brooks, who taught him English poetry and the rudiments of science from a lab he rigged up at home, and instilled in him a lifelong love of reading (the young Jawaharlal devoured Scott and Dickens, Conan Doyle and Twain). Motilal also engaged an eminent Sanskrit tutor, who reportedly had little success with his Anglophone charge. But Brooks, a follower of theosophy — a conflation of Hindu doctrines and Christian ethics that reached its peak of popularity in the last decades of the nineteenth century — obliged Jawaharlal to read the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita in English translation, and the young Nehru even briefly went through a formal conversion to theosophy at age thirteen (though this was soon forgotten by all concerned, including the convert himself). The woman who initiated Jawaharlal into theosophy, Annie Besant, a silver-tongued Englishwoman who had joined the struggle for Indian “home rule,” would remain a powerful influence in the years to come.

Meanwhile, the boy was doted on by his increasingly unwell mother, who superstitiously went to inordinate lengths to protect him from the “evil eye” — that malefic gaze, born of envy or even excessive admiration, which many Hindus believe brings disaster in its wake. She would admonish anyone who commented on his looks, his growth, his talents, or even his appetite (it is said she would give him a private snack before dinner so that he would not eat too hungrily before others and invite comment). Jawaharlal was frequently subjected to ritual attempts to ward off possible afflictions, including the placing of a black dot on the forehead to repel the evil eye, which of course was rubbed off before the lad posed for the studio photographs of the family with Motilal.

Motilal had little time for such distractions as religion or custom; the hereafter concerned him less than the here and now. A freethinking rationalist, he saw in Western science and English reasoning, rather than in Hindu religion or ritual, the real hope of progress for India. He sometimes took this conviction too far: at one point in the 1890s he decreed that no language other than English would be spoken at his home, having forgotten that none of the female Nehrus had been taught any English. Inevitably, when Jawaharlal was just fifteen, his father enrolled him at the prestigious British public school, Harrow.

By an intriguing coincidence, some fifteen years earlier the school had educated (and sent on to Sandhurst) a young man called Winston Spencer Churchill, who after stints in the colonies was already embarking upon a prodigious career in British public life. The two Harrovians would come to have diametrically opposed views of India — dismissive on Churchill’s part, proudly nationalist on Nehru’s. “India,” Churchill once barked, “is not a country or a nation. … It is merely a geographical expression. It is no more a single country than the Equator.” A more liberal-minded Harrovian of the previous century, Sir William Jones, had founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784, translated many Sanskrit classics, and greatly advanced Western appreciation of Indian culture and philosophy. But ironically, it was Churchill’s view of India that would one day make Jawaharlal Nehru’s “invention of India” necessary. “Such unity of sentiment as exists in India,” Churchill wrote, “arises entirely through the centralized British Government of India as expressed in the only common language of India — English.” Jawaharlal Nehru, as the product of the same elite British school as Churchill, would use that education and the English language to complete what he called “the discovery of India” and assert its right to be free of Churchill’s government.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.