Weston, as usual, sat with Marshal and Wren. They were armed with stacks of technical papers on the New Madrid Seismic Zone.

Atkins had taken a seat as far as possible from Marshal. He still didn’t know what to make of that screw-up with the explosives. It seemed impossible that Marshal could have accidentally fired the blasting machine. But he didn’t like thinking about the only other option. Until he had time to sort it out, he resolved to keep a close watch on Marshal.

Thompson, CD headphones draped around his neck, asked for the lights to be dimmed. He wore a pair of beautifully stitched blue and black cowboy boots and a green Western shirt with a white yoke. He’d let his raven hair hang down to his shoulders.

His first image was a two-dimensional view of what everyone was calling the Caruthersville Fault where it intersected with a previously known segment of the New Madrid Seismic Zone.

The fault appeared on the screen as if suspended on the grid—beautiful computer graphics.

The rupture was thirty kilometers deep and extended on a northeasterly line into western Kentucky. It started roughly at Caruthersville, ran across the western edge of Tennessee and up into Kentucky. The fault line ended near Elizabethtown, about thirty miles from Louisville. Lexington was sixty miles away; Cincinnati, 105.

“The total length appears to be about 180 miles,” Thompson said.

Atkins glanced at Elizabeth. That was longer than the original estimate.

When combined with the New Madrid Seismic Zone, the combined fault system reached into six states.

“This is huge,” Thompson observed. “Nothing in North America compares. Not San Andreas. Nothing. The seismic data from other stations in the upper Mississippi Valley indicate aftershock activity on almost every segment of the New Madrid system. Most of it remains concentrated along the Caruthersville Fault.”

A pall of silence followed. The scientists in the room were tired, wrung out. They’d been working for days in a city devastated by the earthquake, where the damage was all around them. Where dead bodies still lay in the streets. They were emotionally drained. It was hard for them to summon up the energy to respond to Thompson’s chilling data.

Atkins thought it might be among the largest intraplate fault systems in the world. Several in Asia were longer. He never would have considered anything like this possible in the continental United States. And all those fault lines were quivering with seismic energy.

It got worse.

Thompson’s next image was another two-dimensional close-up of the Caruthersville Fault, the point where it intersected with one of the older New Madrid segments. Radiating from both lines were literally hundreds of smaller ones, so many they looked like veins connected to major arteries.

“Those are stress fractures,” Thompson said. “In some places, they extend twenty miles or more. I’ve never seen such clear delineations. The seismic waves produced by the explosions slowed dramatically every time they hit one of these fractures.”

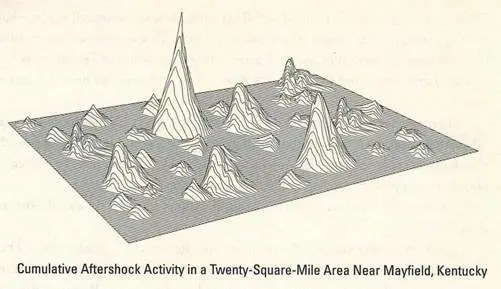

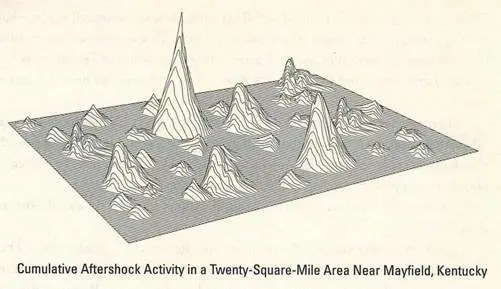

Another image, one of the most dramatic of all, showed a series of sharp peaks that rose up like a mountain chain from the new fault zone. The peaks illustrated cumulative aftershock activity in that area. Each of the taller peaks represented a minimum of twenty aftershocks that had occurred in roughly the same twenty-square-mile area. The proportional ratio was less for the smaller peaks.

As she listened, an oppressive gloom settled over Elizabeth. The complex network of faults and fractures indicated a large amount of strain energy was still in the ground.

“Can you tell us, estimate, how much energy’s been released?” she asked.

Thompson had been waiting for that question. He knew the answer was going to hit hard.

“Our analysis suggests the release of slightly less than 10 ergs of energy to the twenty-fourth power.” An erg was a standard unit of energy.

“Impossible!” Weston exploded.

It meant the 8.4 event had released about as much energy as the daily consumption rate for the entire United States or about as much as the stupendous volcanic eruption at Krakatau in 1883, which darkened the earth’s atmosphere for years with ash and dirt. Only the 1960 Chilean earthquake, a magnitude 8.6, had released more energy, but its range was much smaller. Several hundred miles compared with more than a thousand for New Madrid’s 8.4.

Thompson put it in perspective with another image he projected on the wall. “If the amount of energy released in a magnitude 3 earthquake were represented as a marble, the quake we just had would be a hot air balloon.”

“And the ground’s still shaking,” Elizabeth said, almost to herself. It was hard to understand how any energy could remain after such a massive earthquake and the chain of strong aftershocks.

Walt Jacobs pulled down a wall chart he’d used for lectures. It described, step by step, the chronology of the three great quakes of 1811-1812.

Atkins was distressed to see how much his friend had slipped physically. He looked like he’d lost weight, especially in his thin face. He hadn’t shaved for days, and the beard and dark, sunken eyes gave him a wild, unkempt look. He seemed to be moving in a fog. Just before the meeting, Atkins had found him sitting at a desk, staring into space. He asked whether he’d heard from his wife. Jacobs shook his head. He looked scared. Atkins knew he’d been waiting to hear. There was still no word.

“The first event, the one of December 16, 1811, was conservatively estimated to be in the magnitude 8.1 to 8.3 range,” Jacobs said. As soon as he began to talk, the fatigue seemed to fall off him. He was animated, well spoken. “We’ve estimated that single quake and related aftershocks released only half of the strain energy stored in the fault zone. Only half, ladies and gentlemen.”

Elizabeth whispered to Atkins, “I don’t know if I want to hear the rest of this.”

“Then the second big quake hit on January 23, 1812,” Jacobs continued. “Research indicates it was another magnitude 8-plus event. Like the first one, the shock waves were felt from the Rockies to the East Coast. We believe it released about sixteen percent of the available strain energy.”

So there was still a ton left in the ground, Atkins thought. It was almost unbelievable.

“Again, there was another flurry of severe aftershocks,” Jacobs said. “Then another big one hit. The last in the sequence. It struck at 3:45 on the morning of February 7. A dip slip rupture that radiated over the entire Reelfoot Rift. It’s been variously estimated as high as a magnitude 8.6 and as low as an 8.1.”

Jacobs looked out at the assembled faces. They were hanging on his every word. “The only point I’m trying to make is that plenty of seismic energy remained locked in the ground after the first quake in the sequence.”

Weston stood, shaking his head. “That’s very interesting, Walt. But the fact that we’ve got a lot of elastic strain energy stored in the ground isn’t proof we’re going to have another magnitude 8 earthquake. And that’s what you’re suggesting. Statistically, it’s a virtual impossibility. For all we know, there are structural barriers that will halt the progression no matter how much strain energy remains. There are too many variables. Too many unknowns. I’m not going to approve any public statement to the contrary.”

“You don’t think we should even warn people of the possibility of another major earthquake?” Atkins asked. They’d had this argument a few days earlier, without result.

Читать дальше