Thompson showed the new fault on a map projected on the wall. It appeared to intersect with another major fault segment, the hatchet-shaped top of the NMSZ.

Thompson’s voice had become calmer, almost detached. “The New Madrid Seismic Zone has increased from a series of connected faults roughly 125 miles long to a more complex system that extends for over 400 miles.”

Holleran looked at Atkins. Neither of them had experience with anything like this.

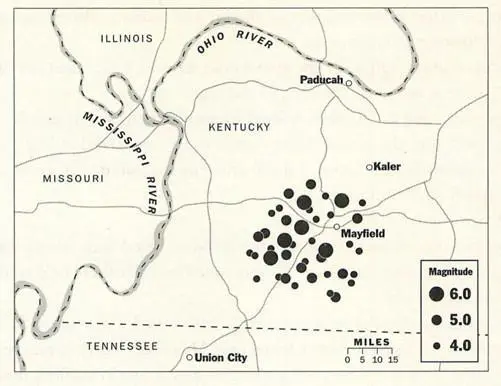

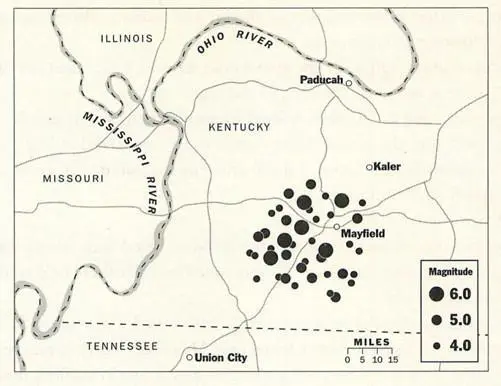

Thompson displayed another image, a map of southwestern Kentucky dappled with a series of dots. Each represented the location of major aftershocks along what Thompson had begun to call the “Caruthersville Fault.” Some were in the magnitude 6 range.

The aftershocks had been recorded by USGS seismic stations at Golden, Colorado; Reston, Virginia; and other locations. Seismographs as far away as Tokyo had also monitored them.

Thompson said, “We’ve been averaging about six hundred aftershocks a day. Most can’t be detected physically. The bigger ones have been bunched along the Caruthersville Fault.”

Holleran knew that Northridge, California, had experienced more than a thousand aftershocks a day for about a month, but they weren’t as strong as these, nowhere near it.

“You’ll note the bigger dots represent the magnitude 6 quakes,” Thompson said.

Holleran counted at least six of them.

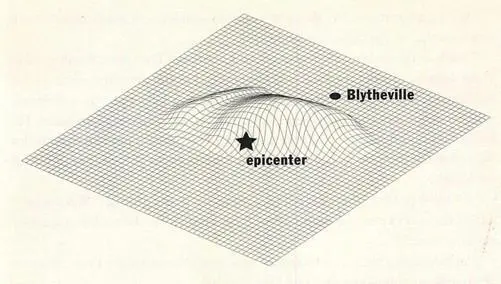

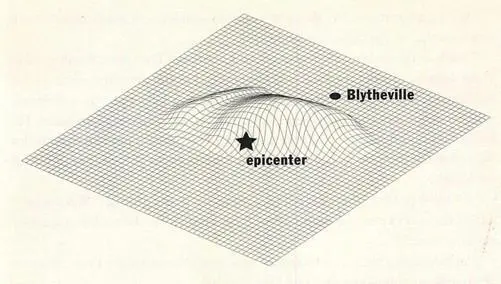

Thompson wasn’t finished with his disturbing sound-and-light show. He punched some keys on the laptop and projected a series of thirty color-enhanced images. The sequence showed how the slippage had radiated out from the quake’s epicenter near Blytheville. Each image represented a second of time.

“You’ll see that the rupture didn’t occur instantaneously or proceed uniformly across the entire fault plane,” Thompson said. “It traveled in a northeasterly direction at about four kilometers a second. Some parts of the plane showed major slippage. Other parts little or none.”

The areas where the most slippage had occurred were called “asperities.” Seismologists had long paid close attention to asperities as the source of energy pulses that reached the surface at different times and places as the earthquake progressed. More specifically, they were areas in a fault that contained the most slippage. The direction and manner in which a big quake ruptured across the fault greatly affected the intensity of the ground motion. The movement was never uniform or instantaneous.

The location and timing of the aftershocks showed, better than any other indicator, the true scope and breadth of the fault.

As he stared at these clusters, Atkins’ uneasiness increased. It was the second fault connected to the New Madrid system to be discovered in less than four days. The first one had revealed itself after the magnitude 7.1 event and extended south of Memphis.

And now this.

Thompson’s computerized images reemphasized for Atkins one of the major facts that distinguished the New Madrid zone from all others he’d studied: its incredible complexity.

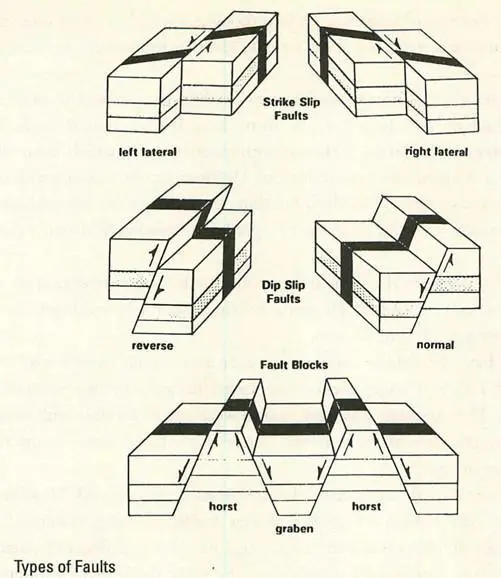

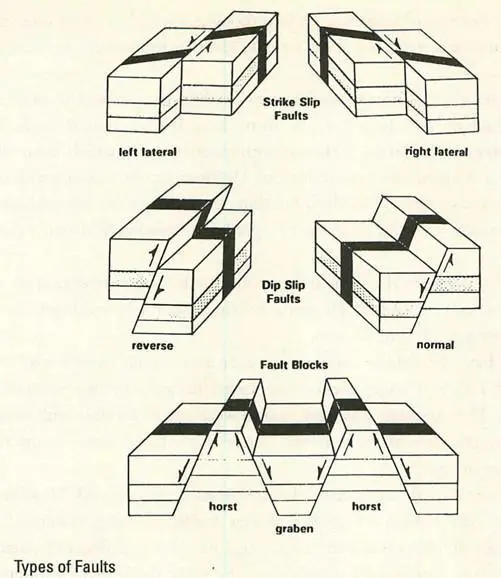

“We’re talking about a multiple event,” Atkins said. “If you try to break it down, you’ve got a seven-foot deformation. My God, I don’t think even Chile had anything like that.” The 1960 quake, the largest one in modern times, registered a magnitude 8.6 on the Richter. “Then you’ve got the dip slip and strike slip subevents on two different fault segments, both previously unknown. And both of them connected to the major fault system. I’ve never encountered that before.”

Thompson displayed an image that illustrated the kind of faults Atkins was talking about. Strike slip faults were primarily horizontal in their shearing movement. Dip slip faults moved down or upward. One of the images showed the distinctive horst and graben effect produced by the faulting process. A graben was a fault block that subsided or dropped down. A horst was one driven upward.

One detail continued to worry Atkins the most: the possibility that the big quakes were forming new faults deep in the earth or bringing old ones back to life.

“It’s not just the complexity and enigma of the events that scares me,” he said. “It’s the way these new faults have opened up. If there’s enough seismic energy left in the ground and one of them goes off, there’s no telling how far the damage will spread.” He reminded everyone of the duration of the 8.4 mainshock. “Over three minutes… I still have to take a deep swallow whenever I think about exactly how long that was.”

Thompson showed another slide, a map of the two new faults that had appeared during the magnitude 7.1 and 8.4 earthquakes and several other major faults that extended across portions of the Mississippi Valley.

“Notice how the 8.4 fault line extends up to the Shawneetown-Rough Creek System,” he said. The image showed how that fault, in turn, abutted two others—the Cottage Grove system, which cut across the bottom of southern Illinois, and the Wabash Valley Fault, running up along the Indiana-Illinois border. Branching off Cottage Grove was the long arm of the Ste. Genevieve Fault System, which started in eastern Missouri and followed the course of the Mississippi River down roughly to its juncture with the Ohio River.

“There it is, ladies and gentlemen,” Thompson said, stepping back to look at the screen. “I hope that worries you half as much as it does me.”

Stan Marshal immediately objected. “We don’t have any physical evidence that these faults are connected,” he said. “And we’re in no position to suggest that an earthquake on one would trigger one on another. That’s way too speculative.”

“The real issue is how much crustal shear strain is left in the ground,” said Mark Wren. “We don’t have enough data yet to run those kinds of projections.”

Wren seldom spoke at these sessions. He seemed like a competent geologist but was overly deferential to Weston, Atkins thought. He had to admit Wren was right. It all came back to getting more satellite readings to measure any new deformation.

Still, the data made him nervous. The new fault line was incredibly active.

Walt Jacobs had been largely silent up to then. It looked as if he hadn’t changed his denim shirt in days. He was withdrawn, moody, which wasn’t like him. Atkins was starting to worry about him. He knew Jacobs was sick with fear about his wife and daughter. He’d heard nothing from them since the quake, and he was still waiting for word from the two graduate students he’d sent to look for them.

“We need to consider the possibility we may be having a repetition of the 1811-1812 events,” Jacobs said. He spoke slowly, deliberately, and immediately drew a sharp response from Weston.

“We don’t have the data to support that even as a serious hypothesis,” Weston said with a flash of anger. He was supported immediately by several other seismologists. They knew he was right, and all were uncomfortable with raising the specter of the big quakes from the last century. There were shouts that Jacobs was out of line.

Continuing as though unaware of the interruption, Jacobs said, “It all happened before—the sudden emergence of new faults, lingering, violent aftershocks, a huge deformation over a vast region. The complicated pattern of ruptures, main shocks, and after shocks. The same thing that’s happening right now.”

Читать дальше