Tim, the chief reporter, rang to congratulate her. “Great job, Dawn. Would love to be a fly on the wall at the Taylors’ this morning.” He didn’t tell her that the editor was delirious or that the Herald ’s sales were up, as was the editor’s annual bonus.

THIRTY-FOUR

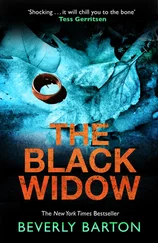

The Widow

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2008

I was shaking when we got into the lawyer’s. Not sure if it was anger or nerves—bit of both probably, and even Mr. Smoothy put his arm around me. “Bloody stunt merchants,” he said to Tom Payne. “We should report their behavior to the Press Council.”

I kept replaying it in my head from the moment I realized it was her. I should’ve recognized her straightaway. I’ve seen her enough times on the telly and in court. But it’s different when you see someone in the street where you’re not expecting them to be. You don’t really look at people’s faces, I think, just their outlines. ’Course, as soon as I really looked at her, I knew it was her. Dawn Elliott. The mother. Standing there with the idiots from the Herald egging her on, accusing my Glen when he’s been found not guilty. It’s not right. It’s not fair.

I suppose it was the shock that made me shout at her like that.

Glen was angry that I told her what I thought. “It’ll just keep everyone going, Jean. She’ll feel she has to defend herself and keep giving interviews. I told you to keep quiet.”

I said I was sorry, but I wasn’t. I meant every word I said to Dawn Elliott. I’ll do a phone-in tonight and say it again. It felt good to say it out loud, in public. People should know it’s all her fault. She was responsible for our little girl and she let her get taken.

They sat me down with a hot drink in the clerk’s room while they got on with the meeting. I wasn’t in the mood for legal stuff, anyway, so I sat quietly in a corner, replaying the row in the street in my head and sort of listening to the secretaries’ chatter. Invisible again.

It took ages for the meeting to end, and then we had to discuss how we were going to get out without the press seeing us. In the end, we went out the back, down an alleyway where they put the bins and bikes. “They won’t be hanging around now, but no point taking chances,” Tom said. “It’ll be on their website by now and all over the paper tomorrow. It’ll increase the damages—just keep thinking about the money.”

Glen shook Tom’s hand, and I just sort of waved. I didn’t want the money. I wanted it to stop.

He was extra nice to me when we got in, taking my coat off and making me sit with my feet up while he put the kettle on.

It was the anniversary today. I’d marked it in my diary with a dot. A little dot that could be a slip of the pen so no one else would know if they looked.

Two years since she was taken. They’d never find her now—the people who took her must have persuaded everyone by now that she was theirs and she must have accepted them as her mum and dad. She’s little, and she probably hardly remembers her real mother. I hope she’s happy and they love her as much as I would if she were here with me.

For a moment I could see her sitting on our stairs, bumping down on her bottom and laughing. Calling for me to come and watch her. She could’ve been here if Glen had brought her home to me.

Glen hadn’t said much since we got back. He’d got his computer on his knee and closed it quickly when I went to sit next to him. “What were you looking at, love?” I asked.

“Just flicking through the sports pages,” he said, and then went to put petrol in the car.

I picked up the computer and opened it. It said it was locked, and I sat and stared at the screen, at the photo of me Glen had put on it. There I was, locked like the computer.

When he came home, I tried to talk to him about the future. “Why don’t we move, Glen? Have the fresh start we keep talking about? We’re never going to escape this unless we do.”

“We’re not moving, Jean,” he snapped at me. “This is our home, and I won’t be driven out of it. We’re going to weather this. Together. The press will forget about us in the end and move on to some other poor sod.”

“They won’t,” I wanted to say. Every anniversary of Bella’s disappearance, every time a child goes missing, every time there is a quiet news day, they’ll come back. And we’ll just be sitting here, waiting.

“There are so many nice places to live, Glen. We’ve talked about living by the sea one day. We could do that now. We could even move abroad.”

“Abroad? What the hell are you talking about? I don’t want to live somewhere I can’t speak the language. I’m staying put.”

So we did. We might as well have moved to a desert island in the end, as we were completely isolated in our little house. Just the sharks circling occasionally. We kept each other company, doing the crossword together in the kitchen—him reading out the clues and writing the answers in while I was still guessing, watching films together in the living room, me learning to knit, him chewing his nails. Like an old retired couple. I’m not even forty yet.

“I think the Mannings’ poodle must’ve died. It’s been weeks since any dog shit has been left on the doorstep,” Glen said conversationally. “It was very old.”

The graffiti persisted. That paint is terrible to get off, and neither of us wanted to stand there in full view, scrubbing at it, so it stayed. “Scum” and “Peedofile” in big red letters on the garden wall. “Kids,” Glen said. “From the local comprehensive, if the spelling’s anything to go by.”

There were letters from the “hate mail brigade” most weeks, but we’d started putting them straight in the bin. You could tell them a mile off. I never saw those tiny envelopes or the green pens they used for sale—the poisonous people must have had their own source of them and the rough, lined notepaper they preferred. I supposed it must be cheap.

I used to look at the handwriting to try to guess what sort of person had sent it. Some were all loops and swirls—the sort of writing on a wedding invitation—and I thought they must have been written by old people. No one else wrote like that anymore.

They were not all anonymous. Some wrote their address in spidery writing on the top—lovely names like “Rose Cottage” or “The Willows”—and then spewed out their bile underneath. I was so tempted to write back and tell them what I thought of them—to give them a dose of their own medicine. I wrote the replies in my head when I was pretending to watch the television, but I didn’t take it any further. It would’ve caused trouble.

“They’re just sick, Jeanie,” Glen said each time one plopped through the letter box. “We should feel sorry for them, really.”

Sometimes I wondered who they were, and then I thought they were probably people like me and Glen. Lonely people. People on the edge of things. Prisoners in their own homes.

I bought a big jigsaw puzzle at the local charity shop. It was a picture of a beach with cliffs and seagulls. It would give me something to do in the afternoons. It was going to be a long winter.

THIRTY-FIVE

The Reporter

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 18, 2009

It’d been a quietish week—Christmas, fast approaching, had filled the paper with festive nonsense and warming stories of adversity overcome. Kate flicked through her notebook more from habit than hope, but there was nothing to pick at. The paper was already full of Saturday reads—long features, shrieking columnists, pages of elaborate Christmas fare and postfestivity diets. Terry looked happy, anyway.

Unlike the crime man, who, passing her desk on his way to the Gents, paused to vent his anger. “My Christmas anniversary piece has been chucked out,” he said.

Читать дальше