That should, perhaps, have reassured her that whoever had cut Lyn’s hair was long gone. But she found it hard to accept. She had been left so completely unnerved. It made no sense at all, and every time she thought of how he must have entered the house while she was so innocently naked and exposed in the shower, she wanted to curl up in a foetal ball and simply shut out the world. If only it was possible to pretend that none of this had happened, that in another moment she would turn over and wake up looking at the digital display on her bedside clock, daylight seeping in around the edges of her curtains.

But she knew that there was no such easy escape, and so she sat, rigid with tension and cold, and waited.

Across the room, the shorn head watched her in the dark, almost scornfully. Amy didn’t know what fear was. Amy was still alive. Amy had hope, Amy had a future.

The telephone rang, and it so startled her that she nearly screamed. She grabbed the receiver. At last!

‘Jack!’

‘Sorry to disappoint. It’s only Tom.’ But she was disappointed. The momentary relief which had flooded her senses receded immediately, leaving her edgy and tense. And in spite of his attempt at flippancy, she detected something strangely off-key in Tom’s tone.

‘What do you want, Tom?’ She hadn’t meant to be so terse.

‘I want you to come down to the lab,’ he said evenly.

‘Why?’

‘I don’t want to go into it on the phone. I just need you here now. As soon as possible.’

‘Tom, have you any idea what time it is?’

‘About three, I should think.’

‘Well, what can you possibly want me there for at three in the morning?’

‘I need you to bring the head and the skull.’

Amy’s feeling of danger momentarily deserted her, to be replaced by consternation. ‘I don’t understand.’

‘You don’t have to understand, Amy.’ Tom’s self-control was deserting him. He sounded tetchy now. ‘Just do it. Please.’

‘Tom...’

‘Amy!’ he nearly shouted. ‘Just do it.’

She almost recoiled from the phone. They’d had their rows over the years, but he had never spoken to her like this. And he seemed, immediately, to regret it.

‘Amy, I’m sorry.’ He was pleading now. ‘I didn’t mean to shout at you. It’s just... this is really important. Just come. Please.’ He paused. ‘Trust me.’

Trust me . How could she not? They had been friends for so long, and he had been with her all the way to hell and back. They were the two words most guaranteed to invoke all the friendship and gratitude she owed him. Trust me . Of course she trusted him. And for all her misgivings, there was no way she could refuse him.

‘It’ll take me forty, maybe fifty minutes.’

The relief in his voice was nearly palpable. ‘Thanks, Amy.’

The phone call had banished the sense of imminent danger in the apartment. And she began to wonder just how much her imagination had played a role in it. She turned on the light again and wheeled across the room to lift the child’s head from the table. She removed the wig before carefully wrapping the head in soft wadding and slipping it into an old hat box that she kept for transporting her heads. She dropped the wig in on top of it and replaced the lid.

As the stair lift droned slowly down to the first landing, her sense of acute vulnerability returned. She still clutched the kitchen knife on top of the hat box. But there was nobody there. Nobody in the bedroom or the bathroom, or in the coat cupboard when she retrieved the thick winter cape she used to drape over her shoulders.

The tiny hall at the foot of the final flight was deserted, cold and unadorned in the harsh yellow lamplight, and the smell of the skull rose up to greet her, through all its layers of plastic. A reminder, if she needed one, that the child was dead, and that they were still in the business of trying to find her killer.

She opened the door, and the night breathed its cold breath in her face. She pulled it shut behind her and motored down the ramp into the deserted square of granite cobbles. A tear opened up suddenly in the cloud overhead, and the briefest glimpse of silver light spilled across the courtyard, vanishing again in an instant. There was not a living soul to be seen, and Amy wondered if she had ever felt more alone. She turned her wheelchair and headed for Gainsford Street and the multi-storey car park.

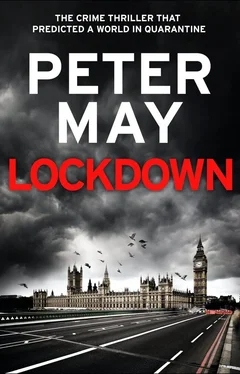

There were times when it was almost possible to believe that the millions of people who had once lived in this great city had simply packed up and left it. In this darkest of the small hours, when there were no vehicles on the road, no lights in any of the windows amongst the rows of silent houses they drove past, it felt abandoned. Lost.

Dr Castelli had left her car at Wandsworth, opting to stay with MacNeil, somewhere on the wrong side of the law. For his part he was glad of the company. The presence in the passenger seat beside him of this odd little lady, in her sensible housebreaking shoes and tweed suit, was comforting in a peculiar sort of way. Human contact. A voice to drown out the one in his head.

And she did like to talk. Perhaps it was nerves. A need to drive out her own demons.

She was talking now about H5N1. ‘Of course, you’ve heard of antigenic shift?’ she said, as if it might have been a topic of everyday conversation.

‘No.’

‘It’s what we call an abrupt, major change in an influenza-A virus. Doesn’t happen that often, but when it does, it creates a new influenza-A subtype, producing new hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins that infect humans. Most of us have little or no protection again them.’

‘And H5N1 is an A virus?’

‘It is. And it’s probably been around for a very long time, in one form or another.’

‘Before it shifted?’

‘Exactly. And when it did that, it became lethal, not only to birds, but to humans as well. Of course, it still had to find an efficient way of transmitting itself from human to human, while retaining its remarkable propensity for killing us. They’ll do that, you know, viruses. Real little bastards! Almost as though they’re pre-programmed to find the best way of killing everything else. A virus only has one raison d’être , you know. To multiply exponentially. And once it starts, it’s a hell of a hard thing to stop.’

‘So what happened to make it transmit so efficiently from human to human?’

‘Oh, recombination. Almost certainly.’

‘Which is what?’

‘Put simply, one virus meets another, they exchange genetic material, and effectively create a third virus. Pure chance whether or not it turns out to be something worse. A kind of little Frankenstein’s monster of the virus world.’

‘But that’s what happened to the bird flu?’

‘Oh, sure. On its travels, H5N1 probably encountered a human flu virus in one of its victims. They got together, swapped the worst, or best, of each of them, and created the nasty little SOB that’s killing everyone now.’

They cruised past the flower market at the junction of Nine Elms Lane and Wandsworth Road, and MacNeil stared thoughtfully downriver towards the floodlit Houses of Parliament, and the unmistakable tower of Big Ben. ‘Could something like that be done, you know, in a lab?’

‘Well, of course.’ Dr Castelli was warming to her subject. ‘With genetic manipulation you could quite easily create an efficiently transmittable version of H5N1. Swap a human receptor binding domain from a human flu virus into an H5 backbone and you’d improve transmission efficiency enormously. The last couple of years, they’ve been doing that in labs all over the world to try to anticipate what a human transmissible H5N1 would look like.’

Читать дальше