Langdon eyed the strange icon.

Rarely did Langdon see a symbol he could not identify. In this case, the symbol was the Greek letter lambda — which, in his experience, did not occur in Christian symbolism. The lambda was a scientific symbol, common in the fields of evolution, particle physics, and cosmology. Stranger still, sprouting upward out of the top of this particular lambda was a Christian cross.

Religion supported by science? Langdon had never seen anything quite like it.

“Puzzled by the symbol?” Beña inquired, arriving beside Langdon. “You’re not alone. Many ask about it. It’s nothing more than a uniquely modernist interpretation of a cross on a mountaintop.”

Langdon inched forward, now seeing three faint gilded stars accompanying the symbol.

Three stars in that position , Langdon thought, recognizing it at once. The cross atop Mount Carmel. “It’s a Carmelite cross.”

“Correct. Gaudí’s body lies beneath the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel.”

“Was Gaudí a Carmelite?” Langdon found it hard to imagine the modernist architect adhering to the twelfth-century brotherhood’s strict interpretation of Catholicism.

“Most certainly not,” Beña replied with a laugh. “But his caregivers were. A group of Carmelite nuns lived with Gaudí and tended to him during his final years. They believed he would appreciate being watched over in death as well, and they made the generous gift of this chapel.”

“Thoughtful,” Langdon said, chiding himself for misinterpreting such an innocent symbol. Apparently, all the conspiracy theories circulating tonight had caused even Langdon to start conjuring phantoms out of thin air.

“Is that Edmond’s book?” Ambra declared suddenly.

Both men turned to see her motioning into the shadows to the right of Gaudí’s tomb.

“Yes,” Beña replied. “I’m sorry the light is so poor.”

Ambra hurried toward a display case, and Langdon followed, seeing that the book had been relegated to a dark region of the crypt, shaded by a massive pillar to the right of Gaudí’s tomb.

“We normally display informational pamphlets there,” Beña said, “but I moved them elsewhere to make room for Mr. Kirsch’s book. Nobody seems to have noticed.”

Langdon quickly joined Ambra at a hutch-like case that had a slanted glass top. Inside, propped open to page 163, barely visible in the dim light, sat a massive bound edition of The Complete Works of William Blake.

As Beña had informed them, the page in question was not a poem at all, but rather a Blake illustration. Langdon had wondered which of Blake’s images of God to expect, but it most certainly was not this one.

The Ancient of Days , Langdon thought, squinting through the darkness at Blake’s famous 1794 watercolor etching.

Langdon was surprised that Father Beña had called this “an image of God.” Admittedly, the illustration appeared to depict the archetypal Christian God — a bearded, wizened old man with white hair, perched in the clouds and reaching down from the heavens — and yet a bit of research on Beña’s part would have revealed something quite different. The figure was not, in fact, the Christian God but rather a deity called Urizen — a god conjured from Blake’s own visionary imagination — depicted here measuring the heavens with a huge geometer’s compass, paying homage to the scientific laws of the universe.

The piece was so futuristic in style that, centuries later, the renowned physicist and atheist Stephen Hawking had selected it as the jacket art for his book God Created the Integers. In addition, Blake’s timeless demiurge watched over New York City’s Rockefeller Center, where the ancient geometer gazed down from an Art Deco sculpture titled Wisdom, Light, and Sound.

Langdon eyed the Blake book, again wondering why Edmond had gone to such lengths to have it displayed here. Was it pure vindictiveness? A slap in the face to the Christian Church?

Edmond’s war against religion never wanes , Langdon thought, glancing at Blake’s Urizen. Wealth had given Edmond the ability to do whatever he pleased in life, even if it meant displaying blasphemous art in the heart of a Christian church.

Anger and spite , Langdon thought. Maybe it’s just that simple. Edmond, whether fairly or not, had always blamed his mother’s death on organized religion.

“Of course, I’m fully aware,” Beña said, “that this painting is not the Christian God.”

Langdon turned to the old priest in surprise. “Oh?”

“Yes, Edmond was quite up front about it, although he didn’t need to be — I’m familiar with Blake’s ideas.”

“And yet you have no problem displaying the book?”

“Professor,” the priest whispered, smiling softly. “This is Sagrada Família. Within these walls, Gaudí blended God, science, and nature. The theme of this painting is nothing new to us.” His eyes twinkled cryptically. “Not all of our clergy are as progressive as I am, but as you know, for all of us, Christianity remains a work in progress.” He smiled gently, nodding back to the book. “I’m just glad Mr. Kirsch agreed not to display his title card with the book. Considering his reputation, I’m not sure how I would have explained that, especially after his presentation tonight.” Beña paused, his face somber. “Do I sense, however, that this image is not what you had hoped to find?”

“You’re right. We’re looking for a line of Blake’s poetry.”

“‘Tyger Tyger, burning bright’?” Beña offered. “‘In the forests of the night’?”

Langdon smiled, impressed that Beña knew the first line of Blake’s most famous poem — a six-stanza religious query that asked if the same God who had designed the fearsome tiger had also designed the docile lamb.

“Father Beña?” Ambra asked, crouching down and peering intently through the glass. “Do you happen to have a phone or a flashlight with you?”

“No, I’m sorry. Shall I borrow a lantern from Antoni’s tomb?”

“Would you, please?” Ambra asked. “That would be helpful.”

Beña hurried off.

The instant he left, she whispered urgently to Langdon, “Robert! Edmond didn’t choose page one sixty-three because of the painting!”

“What do you mean?” There’s nothing else on page 163.

“It’s a clever decoy.”

“You’ve lost me,” Langdon said, eyeing the painting.

“Edmond chose page one sixty-three because it’s impossible to display that page without simultaneously displaying the page next to it — page one sixty-two!”

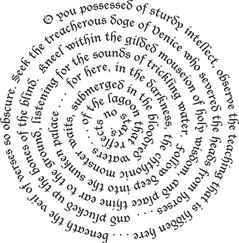

Langdon shifted his gaze to the left, examining the folio preceding The Ancient of Days. In the dim light, he could not make out much on the page, except that it appeared to consist entirely of tiny handwritten text.

Beña returned with a lantern and handed it to Ambra, who held it up over the book. As the soft glow spread out across the open tome, Langdon drew a startled breath.

The facing page was indeed text — handwritten, as were all of Blake’s original manuscripts — its margins embellished with drawings, frames, and various figures. Most significantly, however, the text on the page appeared to be designed in elegant stanzas of poetry.

Directly overhead in the main sanctuary, Agent Díaz paced in the darkness, wondering where his partner was.

Читать дальше