"I think you could work it out," I said. I braced the paddle across the gunwhales and clambered into the canoe. I remembered what Anna had said about emotional commitments: they've made one, I thought, they hate each other; that must be almost as absorbing as love. The barometer couple in their wooden house, enshrined in their niche on Paul's front porch, my ideal; except they were glued there, condemned to oscillate back and forth, sun and rain, without escape. When he saw her next there would be no recantations, no elaborate reconciliation or forgiveness, they were beyond that. Neither of them would mention it, they had reached a balance almost like peace. Our mother and father at the sawhorse behind the cabin, mother holding the tree, white birch, father sawing, sun through the branches lighting their hair, grace.

The canoe pivoted. "Hey," he said, "where you off to?"

"Oh…" I gestured towards the lake.

"Want a stern paddler?" he said. "I'm great, I've had lots of practice by now."

He sounded wistful, as though he needed company, but I didn't want him with me, I'd have to explain what I was doing and he wouldn't be able to help. "No," I said, "thanks just the same." I knelt, slanting the canoe to one side.

"Okay," he said, "see you later, alligator." He unwound his legs and stood up and strolled off the dock towards the cabin, his striped T-shirt flashing between the slats of the trees, receding behind me as I glided from the bay into the open water.

I moved toward the cliff. The sun sloped, it was morning still, the light not yellow but clear white. Overhead a plane, so far up I could hardly hear it, threading the cities together with its trail of smoke; an x in the sky, unsacred crucifix. The shape of the heron flying above us the first evening we fished, legs and neck stretched, wings outspread, a bluegrey cross, and the other heron or was it the same one, hanging wrecked from the tree. Whether it died willingly, consented, whether Christ died willingly, anything that suffers and dies instead of us is Christ; if they didn't kill birds and fish they would have killed us. The animals die that we may live, they are substitute people, hunters in the fall killing the deer, that is Christ also. And we eat them, out of cans or otherwise; we are eaters of death, dead Christ-flesh resurrecting inside us, granting us life. Canned Spam, canned Jesus, even the plants must be Christ. But we refuse to worship; the body worships with blood and muscle but the thing in the knob head will not, wills not to, the head is greedy, it consumes but does not give thanks.

I reached the cliff, there were no Americans. I edged along it, estimating the best place to dive: it faced east, the sun was on it, it was the right time of day; I would start at the left-hand side. Diving by myself was hazardous, there ought to be another person. But I thought I remembered how: we took the canoes or we built rafts from strayed logs and board ends, they would often snap their ropes and escape in the spring when the ice went out; sometimes we would come across them again later, drifting loose like pieces broken from a glacier.

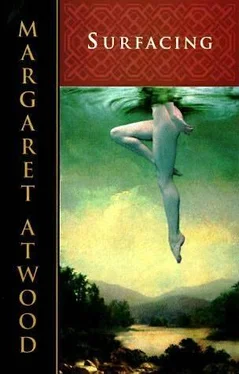

I shipped the paddle and took off my sweatshirt. I would dive several feet out from the rockface and then swim down and in: otherwise I'd risk hitting my head, the drop looked sheer but there might be a ledge underwater. I knelt, facing backwards with both knees on the stern seat, then put a foot on each gunwale and stood up slowly. I bent my knees and straightened, the canoe teetered like a springboard. My other shape was in the water, not my reflection but my shadow, foreshortened, outline blurred, rays streaming out from around the head.

My spine whipped, I hit the water and kicked myself down, sliding through the lake strata, grey to darker grey, cool to cold. I arched sideways and the rockface loomed up, grey pink brown; I worked along it, touching it with my fingers, snail touch on slimesurface, the water unfocusing my eyes. Then my lungs began to clutch and I curled and rose, letting out air like a frog, my hair swirling over my face, towards the canoe, where it hung split between water and air, mediator and liferaft. I canted it with my weight and rolled into it over the side and rested; I hadn't seen anything. My arms ached from the day before and the new effort, my body stumbled, it remembered the motions only imperfectly, like learning to walk after illness.

I waited a few minutes, then moved the canoe further along and dived again, my eyes straining, not knowing what shape to expect, handprint or animal, the lizard body with horns and tail and front-facing head, bird or canoe with stick paddlers; or a small thing, an abstraction, a circle, a moon; or a long distorted figure, stiff and childish, a human. Air gave out, I broke surface. Not here, it must be further along or deeper down; I was convinced it was there, he would not have marked and numbered the map so methodically for nothing, that would not be consistent, he always observed his own rules, axioms.

On the next try I thought I saw it, a blotch, a shadow, just as I turned to go up. I was dizzy, my vision was beginning to cloud, while I rested my ribs panted, I ought to pause, half an hour at least; but I was elated, it was down there, I would find it. Reckless I balanced and plunged.

Pale green, then darkness, layer after layer, deeper than before, seabottom; the water seemed to have thickened, in it pinprick lights flicked and darted, red and blue, yellow and white, and I saw they were fish, the chasm-dwellers, fins lined with phosphorescent sparks, teeth neon. It was wonderful that I was down so far, I watched the fish, they swam like patterns on closed eyes, my legs and arms were weightless, free-floating; I almost forgot to look for the cliff and the shape.

It was there but it wasn't a painting, it wasn't on the rock. It was below me, drifting towards me from the furthest level where there was no life, a dark oval trailing limbs. It was blurred but it had eyes, they were open, it was something I knew about, a dead thing, it was dead.

I turned, fear gushing out of my mouth in silver, panic closing my throat, the scream kept in and choking me. The green canoe was far above me, sunlight radiating around it, a beacon, safety.

But there was not one canoe, there were two, the canoe had twinned or I was seeing double. My hand came out of the water and I gripped the gunwale, then my head; water ran from my nose, I gulped breath, stomach and lungs contracting, my hair sticky like weeds, the lake was horrible, it was filled with death, it was touching me.

Joe was in the other canoe. "He told me you went over this way," he said. He must have been almost there before I dived but I hadn't seen him. I couldn't say anything, my lungs were urgent, my arms would hardly pull me into the canoe.

"What the hell are you doing?" he said.

I lay on the bottom of the canoe and closed my eyes; I wanted him not to be there. It formed again in my head: at first I thought it was my drowned brother, hair floating around the face, image I'd kept from before I was born; but it couldn't be him, he had not drowned after all, he was elsewhere. Then I recognized it: it wasn't ever my brother I'd been remembering, that had been a disguise.

I knew when it was, it was in a bottle curled up, staring out at me like a cat pickled; it had huge jelly eyes and fins instead of hands, fish gills, I couldn't let it out, it was dead already, it had drowned in air. It was there when I woke up, suspended in the air above me like a chalice, an evil grail and I thought, Whatever it is, part of myself or a separate creature, I killed it. It wasn't a child but it could have been one, I didn't allow it.

Water was dripping from me into the canoe, I lay in a puddle. I had been furious with them, I knocked it off the table, my life on the floor, glass egg and shattered blood, nothing could be done.

Читать дальше