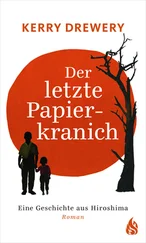

“I still need to be sure,” says Takeda. “That’s why I’ve decided to bring in Reizo Shiga. Thanks to Yori I now know where the Suicide Club is.” Listen to yourself, he thinks. Inside I’m breaking down at a rate of knots, but on the outside I’m still the perfect Japanese cop.

“Why did you tell me the whole story?”

“You put me on the spot,” says Takeda dryly. “You have a good eye for… eh… details.”

She laughs and touches his arm for an instant in a gesture of reconciliation and consolation.

“I hope I didn’t hurt you.”

“You know how proud the average Japanese man can be.”

“You aren’t the average Japanese man, inspector.” Was she flirting with him? Maybe she was still suffering from shock after everything that had happened. Takeda’s police work has taught him that people are much more vulnerable than they like to think. This German woman’s slender, stringy build and delicate joints makes her appear fragile, but he’s convinced in the meantime that she’s capable of more than she would probably admit.

“What a day,” says Beate. She gestures with her head in the direction of the police doctor’s apartment. The setting sun casts a halo of light around her head. “But if I understood her right, Yori’s days are always hectic. I couldn’t live like that. Or perhaps…” She laughs. “There’s this sense of excitement, d’you understand?” She sees the look in his eyes and blushes. “Yori inspires me.”

Takeda wants to leave. What’s holding him back? Inspiration can wait.

Instead he asks: “Why do you think Yori is innocent?”

Beate blinks, feels cornered, but pulls a stubborn face: “My gut tells me. But you wouldn’t understand that, would you, inspector. You’re a man of facts, if I’m not mistaken?”

The word “no” is on the tip of Takeda’s tongue, but he backs down and agrees.

“I often see images when I look at people,” says the photographer. “There’s probably something wrong with me.” The inspector has the impression that he can taste her loneliness. Or is it his own? He can’t help noticing yet again how driven and focussed he feels when he takes risks, when he goes against his training, pushes his position to one side, ignores his innate docility. He’s curious to know what images the photographer sees when she looks at him.

“What do you make of Yori?”

The German hesitates for a moment. “She stumbled into my hotel room in a state, sobbing, confused. She reminded me of the young mother in one of my father’s books, the same tears in her eyes. I was flicking through it only yesterday; a bizarre photo of the corpse of a baby taken here in the city in 1945 by Satsuo Nakata, just after the bomb. My father and Nakata were friends. He put together a penetrating collage of the incident based on pictures taken in the still burning embers of the city. The mother, badly burned, then the corpse, misshapen and bloated, like a lump of putty in the charred rubble, then a close-up of a chrysanthemum painted on the child’s left heel. The father, a young artist, had painted the flower on his little son’s body as an indictment against the emperor. In Japan, the chrysanthemum is the symbol of your emperor’s ‘divinity’, inspector. Where I come from they’re associated with cemeteries.” The photographer makes a dismissive gesture. “I don’t know why that image came to mind. Perhaps it has to do with a photo I saw on the front cover of one of your magazines, just two days ago, a photo of a deformed dead baby. I was struck by the similarity between the two photos although there’s fifty years between them. I remember my father telling me that the father of the dead baby in Nakata’s collage had made a clay replica of his dead son in 1958, with the same chrysanthemum on his heel, and placed it at the foot of the Peace Monument. Little was made of what he did. People preferred to sweep that kind of thing under the carpet back then, because it was still seen as pointing the finger at the imperial family. Perhaps someone heard about it and left this new dead baby as a reminder of the incident. My photography is based on signs , inspector. That’s why I’d like to take a picture of Yori under the monument with a replica of such a baby in her arms. But perhaps I shouldn’t be telling you this. Just like my father you’ll probably think I’m too eager to mimic reality and call the result art.”

Beate Becht takes a step back when Takeda scowls, opens the car door and returns in great haste to Adachi’s apartment.

Hiroshima – Funairi Hospital – Xavier Douterloigne – evening, March 14 th1995

“How’s the patient doing, doctor?”

“I think we need to keep him in a coma for a couple of days more. He’s not out of the woods, but there’s hope. He mumbled a few words earlier, in Dutch I guess. If you ask me he’ll pull through. Whether the poison from the Irukandji has affected his brain is another matter. But, let’s say I’m optimistic.”

“Why?”

“When he was talking there were tears in his eyes. Sadness is one the mind’s higher expressions, honourable colleague.”

* * *

So what happened exactly? Month after month the same question, from friends, acquaintances. Compassion from some, others suspicious. Xavier Douterloigne couldn’t answer them. He wanted to, but something was standing in the way.

What was there to say? That it was his fault his sister Anna had ended up in a wheelchair and committed suicide six months later?

His parents had urged him not to think such thoughts. It was fate, there was nothing else to it. It was sheer accident that Xavier was there when it happened.

They wanted to protect him, their darling son, he was sure of that.

But for him the decision was made: he was to blame. His parents didn’t want to tell him how she had died. It only made him more determined to find out. He started by calling Den Ommeloop , the home where Anna had been staying since the accident. He made an appointment and met up with one of her counsellors, a bearded young man with glasses and an oily voice. Xavier came straight to the point and asked how Anna had committed suicide. The counsellor blinked at the word. He told him that Anna had been having trouble moving her arms in the last few weeks before her death as a result of her damaged nervous system. She could no longer get out of the wheelchair by herself, in spite of the fact that she had even been able to walk a little at the beginning, albeit with difficulty and a lot of assistance. But she hadn’t been unhappy, the counsellor told him. She had made friends in the home. Xavier listened patiently, but had to bite his lip when the man told him that they weren’t certain Anna’s death was suicide. “We think it may have been a simple household accident,” he added. Xavier asked him to explain. The counsellor responded with another question: “Didn’t your parents tell you it was probably an accident?” Xavier informed the man that his parents were thoughtful and considerate people and that they had wanted to spare him in spite of their own pain, but he still insisted on knowing how Anna had ended her life. They pussyfooted around the topic for a while. “Do I have to force my parents to tell me? Is that what you want?” said Xavier finally. “They’ve been through enough. It’s your duty to tell me what happened.” The man stared at him and his defensive wall slowly but visibly melted. He nodded. His voice sounded flat, as if his vocal cords where under pressure. “There was a birthday party. It was busy, lots of people milling around. There was a deep fat fryer in the kitchen, industrial size. Everyone was wearing party hats and singing, clapping, that sort of thing. Anna disappeared into the kitchen without anyone noticing. The fryer… hot oil everywhere… no one saw it happen.”

Читать дальше