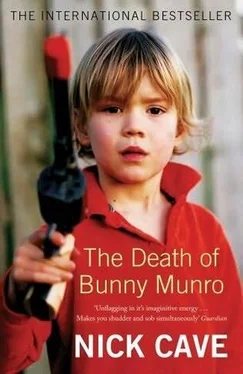

The crowd hoot and stomp their feet as the little man shuffles around the stage making suggestive movements with his tiny, gloved hands and grinding his child-like hips.

Bunny feels a thread of perspiration wind its way down the side of his face and he pulls a handkerchief from the pocket of his jacket and presses it against his forehead. The musician looks at Bunny with an expression of concern or sympathy or something.

‘What are you doing here, man?’ he asks.

‘I’m just trying to put things right, you know,’ says Bunny.

‘Uh-huh, I hear you,’ says the musician. ‘We’ve got to love one another or die, brother.’

‘Yeah, I heard that,’ says Bunny, and again a swell of regret blooms within him and he puts his hand up to his heart.

‘It’s super-glue, baby,’ says the musician, and blows softly into his saxophone. ‘It keeps the heart of the world pumping.’

Bunny peers around the curtain again, and the mirrorball that hangs from the ceiling of the ballroom has begun to revolve and splinters of silver light dance across the faces of the crowd and Bunny sees Georgia, standing in the front row, a thing of certain beauty, proud-looking, almost regal, in a cream chiffon evening dress with scarlet sequins sewn across its bodice like a spray of arterial blood. Her yellow hair hangs in loose ringlets around her lavender eyes and she sways, back and forth, to some inner song, a content smile upon her face. Zoë and Amanda stand each side of Georgia dressed in identical indigo trouser suits. Bunny notices that Zoë now has the same candy-coloured hair extensions as Amanda, and they look happy.

Standing nearby, Bunny sees the Tae Kwon Do black belt, Charlotte Parnovar, dressed in a Mexican peasant skirt and a white embroidered blouse, and as Bunny unconsciously traces his fingers along the lumped bridge of his nose he sees that her face looks softer, less severe, all evidence of the unsightly cyst on her forehead gone.

Bunny sees Pamela Stokes (Poodle’s ‘gift’) with her arm around the waist of the cuckolded Mylene Huq from Rottingdean, both smiling and stealing shy and coquettish glances at one another.

Bunny recognises Emily, the cashier from McDonald’s, dressed in a snug yellow top and tight red trousers, her skin glowing, gazing about the Empress Ballroom as though she has never seen anything so beautiful in her life and applauding enthusiastically as the strange little MC, with the pink toupee, raises his hand to quieten the crowd.

‘But seriously, folks, before the fun begins, we’ve got a gentleman who has come along tonight and wants to say a few words to you.’

Bunny wipes his face with his handkerchief and says to the musician with the saxophone and the moustache, ‘I guess this is me.’

‘Knock ’em dead, brother,’ says the musician, and he pats Bunny on the back. ‘Knock ’em dead.’

Bunny takes a final, firing-squad suck of his Lambert & Butler and grinds it out on the floor. Then he pulls the curtain aside, pats at his lovelock and walks onto the stage as the MC executes a dainty little two-step, throws out his arms and says, ‘So without further ado-da-do, could we have a big round of applause for Mr Bunny Munro!’

Bunny walks onstage to blind and uproarious applause. He enters an apron of red light that spills across the stage like splashed ink. He registers the foot stomps and cheers and whistles, and for a brief moment Bunny feels the air of compacted dread loosen around his heart and thinks that, all things considered, his plan may not be so foolhardy as he had previously thought and sending out the invitations to these women was perhaps not such a dumb idea after all. But as he stretches out his hand and sees the blood-coloured light pool in his palm like a cup of gore, he understands that nothing in this world is ever that easy. Why would it be? He walks closer to the lip of the stage, plants his feet firmly on the floorboards and peers into the audience.

He sees, with a shamed stricture of the heart, the old blind lady, Mrs Brooks, in dark glasses and pink lipstick, seated in a wheelchair. Her skin looks considerably younger, Bunny notices, and as she performs her metronomic rocking and claps her ringed hands together, she appears sprightly and newly energised. Behind her, a pretty young carer stands, one hand resting affectionately on the old lady’s shoulder.

To one side of her, Bunny sees, dressed in a dazzling mulberry taffeta cocktail dress, the young girl from The Babylon Lounge in Hove that Bunny date-raped. She is sharing a joke and laughing together with a dark-eyed beauty in sateen drainpipes and gold pumps that he had a similar thing with after a night at The Funky Buddha. Bunny feels a shamed flush of blood to the throat.

He sees a girl with long, ironed hair and crazy kohled eyes and cupid-bow lips, and he recognises her as the Avril Lavigne look-alike from the bungalow in Newhaven. Beside her stands Mushroom Dave, tapping his foot and dressed in a black suit and tie, his arm thrown protectively around her shoulders, a lit cigarette dangling from his mouth. He whispers something to the girl and they look at each other and smile.

And so it goes, Bunny looks over there and looks over here and looks somewhere in the middle and sees someone from this place and then someone from that place and someone from some other place altogether. On and on it goes, faces rising from the mossy depths of his memory, each with their burning attendant shame – Sabrina Cantrell, and Rebecca Beresford, and Rebecca Beresford’s beautiful young daughter – and over there, caught in the roaming spotlight, he sees Libby’s mother, Mrs Pennington, who is smiling now, smiling and rubbing the shoulders of her stricken, chair-bound husband.

More and more he sees them, standing at the front of the stage, swaying on the dance floor, standing on tiptoes at the back of the hall, waving from the little ornamental balconies – all of them and all the others, in every shape and form and incarnation, some half-recalled and some half-forgotten and some barely a smudged fingerprint on his memory – but all looking glorious and radiant and altogether perfect.

From this council estate and this broken-down apartment and this one-bedroom flat and this down-at-heel hotel, from this dying seaside town and from that dying seaside town, Bunny sees them all coming towards him, from down the days and months and dreadful years of his life, the great teeming parade of the sorrowful, the grieving, the wounded and the shamed – but look! Look at their faces! – all happy now and happy and altogether happy in the eternally beautiful Empress Ballroom at Butlins Holiday Camp in Bognor Regis.

Then, as Bunny steps, squinting, into the spotlight and taps the microphone twice with his index finger, he sees, at the very front of the stage, River the waitress from the breakfast room of the Grenville Hotel – looking more lovely than he can imagine anyone could ever look – stepping angrily from the crowd and thrusting forth her arm and extending one purple finger and screaming through her teeth, ‘ My God, it’s him! ’

Suddenly the atmosphere undergoes a momentous change. The applause, like an inverted roar, is sucked from the room and there is a whirl of confusion and all the furious light bulbs of recognition ignite at the same time. Then follows a howl of outrage that breaks across Bunny with such force that he is propelled backward and almost knocked off his feet.

Bunny steps back to the microphone, leans in and says, into the purgatorial storm, ‘My name is Bunny Munro. I sell beauty products. I ask you for one minute of your time.’

Bunny stares down at the audience and begins his testimony.

Bunny tells the crowd how he was involved in a head-on collision with a concrete mixer truck. He tells them how he was struck by lightning. He explains how his nine-year-old son was almost killed. He talks, to the audience, in terms of a miracle or a wonderment, and he puts forward the question as to why he was spared.

Читать дальше