Vicki Mackenzie

Cave in the snow

A western woman’s quest for enlightenment

For my mother, Rene Mackenzie (1919-1998), the first spiritual woman in my life; with deep gratitude for her unfailing love, wisdom and support.

In retrospect, it was a curious place to meet her. The time was midsummer, the place Pomaia, a little town perched among the magnificent hills of Tuscany about an hour’s drive from Pisa. It was late afternoon and the air was filled with the aroma of dry heat and the scent of pine needles. The once-grand mansion with its ochre-coloured walls, high arched doorways, and castellated roof shimmered in the August sun and only the sound of the cicadas broke the silence of the siesta. In a few hours’ time the town down the road would come alive for the evening. The small shops selling that odd assortment of salami, biscotti and sandals would open and the old men would gather in the square to discuss municipal business and the affairs of the regional Communist party. The sheer lusciousness of Italy, where all things seem to conspire to bring pleasure to the senses, could not have contrasted more radically with the world that she had come from.

The first time I saw her she was standing in the grounds of the mansion under the shade of a copse of trees – a somewhat frail-looking woman in early middle age, with fair skin and a rather rounded back. She was dressed in the maroon and gold robes of an ordained Buddhist nun and her hair was cropped short in the traditional manner. Standing all around her was a group of women. You could see at a glance that the conversation was animated, the atmosphere intimate. It was an arresting scene, but on a month-long Buddhist meditation course not particularly unusual.

I and about fifty others had gathered there, drawn from all over the world, to attend the course. These events had become a regular and welcome part of my life ever since I had stumbled upon the lamas in Nepal back in 1976 and discovered the richness of their message. Lively discussions, such as those I was witnessing, were a welcome break from the long hours of sitting cross-legged listening to the words of the Buddha or attempting the arduous business of meditation.

Later that night, eating dinner under the stars, mopping up the olive oil with large chunks of bread, the man sitting next to me drew my attention to the woman again. She was sitting at a table, once more surrounded by people, talking enthusiastically to them.

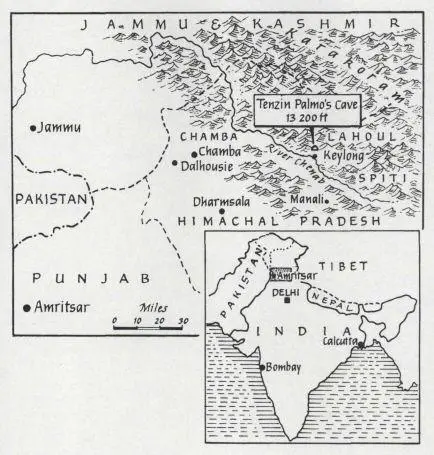

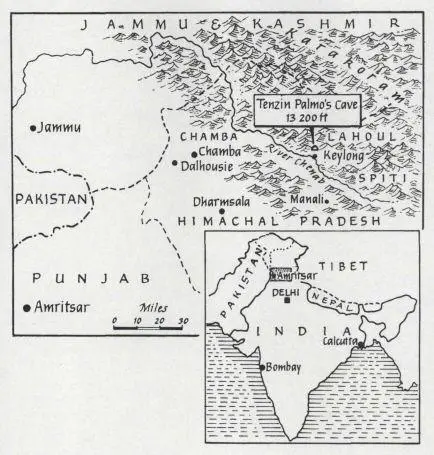

’That’s Tenzin Palmo, the Englishwoman who has spent twelve years meditating in a cave over 13,000 feet up in the Himalayas. For most of that time she was totally alone. She has only just come out,’ he said.

The glance now was more than cursory.

Over the years, I had certainly read about such characters the great yogis from Tibet, India and China who forsook all worldly comfort to wander off to some remote cave to engage in profound meditation for years on end. These were the spiritual virtuosi, their path the hardest and loneliest of all. All alone, I read, dressed in a simple robe or flimsy loincloth, they faced the fiercest of elements – howling gales, raging blizzards, freezing cold. Their bodies became horribly emaciated, their hair grew matted and long to their waists. They faced wild animals and gangs of robbers who, having no regard for their sanctity, beat them into bloody pulp and left them for dead. But all this was nothing compared to facing the vagaries of their own minds. Here, cut off from the distractions of ordinary life, all the demons lying just beneath the surface began to rise up and taunt. The anger, the paranoia, the longings, the lust (especially the lust). They too had to be overcome if the victory was to be won. Still they persevered. What they were after was the most glittering prize of all – Enlightenment, a mind blown wide open to encompass universal reality. A state in which the unknowable was made known. Omniscience, no less. And accompanying it a sublime happiness and an inconceivable peace. It was the highest state of evolution humankind could ever achieve.

So I had read. I never thought I would actually meet such a person but here in Pomaia, Italy, was a character who had seemingly stepped out of the pages of myth and legend and who was now sitting casually among us as though she had done nothing more momentous than just got off a bus from a shopping trip. Furthermore this was not an Eastern yogi, as the tales had told, but a contemporary Westerner. More astonishing still, a woman.

The mind buzzed with myriad questions. What had driven a modern Englishwoman to live in a dank, dark hole in a mountainside like a latter-day cavewoman? How did she survive in that extreme cold? What did she do for food, a bath, a bed, a telephone? How did she exist without the warmth of human companionship for all those years? What had she gained? And, more curiously, how had she emerged from that excessive silence and solitude as chatty as a woman at a cocktail party?

The immediate rush of curiosity, however, was quickly followed by unabashed admiration and a little awe. This woman had ventured where I knew I would never tread.

Her thirst for knowing, unlike mine, had pushed her beyond the safe confines of a four-week meditation course with its exit clause guaranteeing a speedy return to ordinary life. Retreat, I knew from pitifully small experience, was infinitely hard work involving endless repetition of the same prayers, the same mantras, the same visualizations, the same meditations – day in, day out. You sat on the same cushion, in the same place, seeing the same people, in the same location. For someone steeped in the modern ethos of constant stimulation and rapid change, the tedium was excruciating. Only the tiniest shimmer of awareness, and the unaccustomed feeling of deep calm, made it worthwhile. Ultimately retreat was a test of endurance, courage and faith in the final goal.

The next day I saw her again in the garden, this time sitting alone, and seeing my chance I approached. Did she mind if I joined her for a little while? The smile stretched from ear to ear in greeting and a pair of the most penetrating blue eyes gazed steadily into mine. There was calmness there, and kindness, laughter too, but the most outstanding quality was an unmistakable luminosity. The woman virtually glowed. In fact she was a most interesting-looking person – she had sharp features, a long pointed nose and small neat ears. Maybe it was her cropped hair and lack of make-up but there was also something decidedly androgynous about her, as though a sensitive male were lodging within.

We began to chat. She told me that she was now living in Assisi in a small house in the garden of a friend’s place, and was enjoying it immensely. She had been called there, she said, when her time in the cave had come to an end. It seemed a natural place to go. I learnt that she had been ordained back in 1964, when she was just twenty-one, long before most of us even knew Tibetan Buddhism existed. That made her, I reckoned, the most senior Tibetan Buddhist nun in the Western world. Thirty years of celibacy, however, was a long time. Hadn’t she ever wished for a partner, marriage or children in all those years?

’That would have been a disaster. It wasn’t my path at all,’ she replied, throwing back her head and laughing. I hadn’t expected such animation after twelve years in a cave.

What had led her there, to that cave, I asked.

‘My life has been like a river, it has flowed steadily in one direction,’ she replied, and then added after a pause, ‘The purpose of life is to realize our spiritual nature. And to do that one has to go away and practise, to reap the fruits of the path, otherwise you have nothing to give anyone else.’

Читать дальше