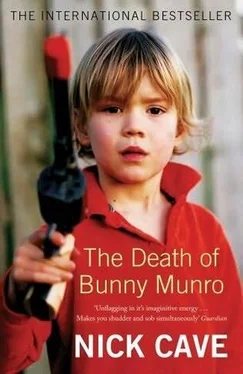

‘I thought that’s what you were doing,’ says Bunny.

‘He needs to be in hospital, Mr Munro.’

Miss Lumley takes a step forward and presses the keys into Bunny’s hand and looks him up and down.

‘What happened to you?’ she asks.

‘He won’t go into hospital, you know that,’ says Bunny, leaning against the wall for support, the weight of the last few days hanging across his shoulders like bags of cement.

‘Perhaps you could both go in,’ says Miss Lumley, reaching up and gently touching the side of Bunny’s nose. ‘You look worse than he does.’

‘You don’t look too hot yourself,’ says Bunny, and smiles and reaches into his jacket pocket and pulls out his flask of Scotch.

‘Drink?’

Miss Lumley smiles back. ‘It’s not been easy. I am a patient woman, Mr Munro. I have tried my best. I simply will not subject myself to the level of abuse I have been receiving. I’m sure you understand. Your father is a very sick man,’ she says, placing her hand on her chest. ‘Here,’ she says, then taps her head, ‘… and here.’

Bunny takes a hit from the flask, sticks a Lambert & Butler in his mouth and Zippos it as Miss Lumley looks down at Bunny Junior.

‘Hey, darling,’ she says.

Bunny Junior waggles his Darth Vader figurine.

‘I got hit in the ear,’ he says.

Miss Lumley bends down and, pushing her spectacles up the bridge of her nose, examines the boy’s tiny wound.

‘I’ve got something for that,’ she says and opens her satchel and produces a small tube of antiseptic cream and a box of plasters. She dabs a small amount of the cream on the tip of his ear and covers it with a tiny circular, flesh-toned plaster.

‘You have been in the wars,’ says Miss Lumley, closing her satchel.

‘You should see the other guy,’ says Bunny Junior, and looks up at his dad and smiles.

Miss Lumley turns to Bunny.

‘He’s a sweetheart,’ she says.

Bunny sucks on his Lambert & Butler, his hand trembling, an electrified nerve jumping under his right eye, a rivulet of perspiration trailing down the side of his face.

‘Seriously, Mr Munro, are you OK?’

‘Hey,’ says Bunny, ‘it’s visiting day.’

‘I understand your pain,’ says Miss Lumley, placing her hand on his arm. She picks up her satchel. ‘Get your father to a hospital, Mr Munro,’ and she disappears down the stairs.

Bunny jiggles the bunch of keys in his hand, wraps his fingers around them and looks at Bunny Junior.

‘Oh, man,’ he says. ‘Here we go.’

The boy looks back at him with his dismantled smile, his head angled to the side, and then together – father and son – they mount the final set of stairs.

Bunny tucks in his shirt and rearranges his hair and straightens his tie and drains the remainder of his flask of Scotch and sucks the last gasp out of the Lambert & Butler and turns to Bunny Junior and says, ‘How do I look?’ and without waiting for an answer knocks three times on the door of Flat 17 and takes a precautionary step backward.

‘Piss off, you bitch!’ comes a roar, from inside. ‘I’m busy!’

Bunny leans close to the door and says, ‘Dad! It’s me! Bunny!’

Bunny hears a terrible hacking from within. There is a clacking sound and scrape of furniture, a chain of raw expletives and the door opens and Bunny Munro the First stands in the doorway, small and bent, dressed in a brown Argyll jumper with snowflakes and a white polar bear on the front, a nicotine-coloured shirt and a mangled pair of brown corduroy slippers. The zipper gapes open in his trousers and faded blue tattoos peek from the sleeves of his jumper and the open neck of his shirt. The skin on his face is as grey as pulped newspaper and the gums of his dentures are stained a florid purple, the teeth bulky and brown. A sullage of colourless hair spills down the back of his egg-shaped skull, like chicken gravy. He brings with him an overpowering stench of stale urine and medicinal ointment. In one hand he holds a heavy cleated walking stick and in the other, a grimly unpleasant handkerchief. He looks at Bunny and clacks his dentures.

‘Like I said, piss off! ’ He slams the door in Bunny’s face.

‘Oh, man,’ says Bunny, putting the key in the door and turning it. ‘Just don’t say anything,’ he says to Bunny Junior out of the side of his mouth, and together they enter the room.

The bedsit is small and unventilated and filled with a layer of stale cigarette smoke. The storm hammers at the windows behind lace curtains yellow with age, and in a tiny kitchen to the side, a kettle shrieks. The old man has sat himself in a sole leather armchair in front of the TV, his walking stick resting across his knees. Behind him a mahogany standard lamp with a tasselled shade casts a fierce light on the back of the old man’s elongated skull. On the TV, a pornographic video involving a teenage girl and a black rubber dildo plays out in colour-saturated reds and greens. The old man pushes his gnarled fist into the lap of his rancid grey trousers, claws at his crotch and proclaims, ‘The fucking thing don’t work!’

The old man looks up from his chair and rubs at his jaw and out of one shrewd eye he scrutinises Bunny’s unfortunate demeanour. He sucks air through his psychedelic dentures, points at Bunny’s red rosette nose and says, ‘How did you get that? Raping an old lady?’

Bunny touches Mrs Brooks’ rings in his jacket pocket and with a twinge of shame or something says, ‘What you need is a nice cup of tea, Dad,’ and walks into the kitchen and turns the screaming kettle off.

‘No, I don’t,’ says the old man. ‘What I need is to get my fucking rocks off!’ and he scrabbles at the flies of his trousers again.

Bunny crosses the room and hits the switch on the TV.

‘Perhaps we can turn this off, Dad,’ he says.

‘Give us a fag, then,’ snorts the old man and wipes at the foam in the corners of his mouth. ‘That fucking bitch stole mine.’

Bunny crosses the room and hands his father his pack of Lambert & Butlers and the old man sticks one between his lips and puts the pack in the top pocket of his shirt. Bunny lights his father’s cigarette as Bunny Junior walks across the room to a little birdcage sitting on an antique Sutherland end-table by the window. Inside it, on a perch threaded with ivy, sits a tiny mechanical bird with red and blue wings. Bunny Junior runs his fingers along the gilded bars of the cage and the little automata rocks on its perch.

‘Come on, Dad, let’s make you a nice cup of tea,’ says Bunny.

‘I don’t want a nice cup of tea ,’ sneers the old man and drags on his cigarette, then presses his handkerchief to his mouth and embarks on a seemingly endless bout of coughing that bends his old body double and brings dark, yellow tears to his eyes.

‘Are you all right, Dad?’ asks Bunny.

‘Eighty fucking years old and I go and get lung cancer,’ he says and spits something unspeakable into his handkerchief. ‘Yeah, I’m just fucking great.’

‘Is there anything I can do, Dad?’ says Bunny.

‘Do? You? You must be fucking joking,’ says the old man.

Bunny Junior turns the gold key in the front of the bird cage and the automata jumps to life and sings a song in a series of short sweet notes, its beak clacking open and shut, its red and blue wings lifting and falling. A look of immense pleasure passes across the boy’s face.

‘Don’t break that thing. It’s worth a bloody fortune,’ says the old man who is attempting to pull the zipper up on his flies, working at it with his twisted fingers.

‘Sorry, Granddad,’ says the boy.

The old man stops what he is doing and looks up at Bunny, the cigarette clamped between his dentures, threads of skin like worn rubber bands looping at his throat.

Читать дальше