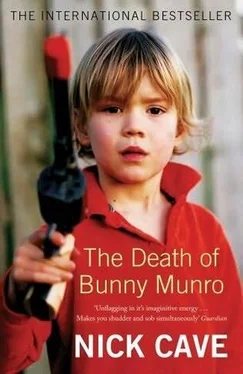

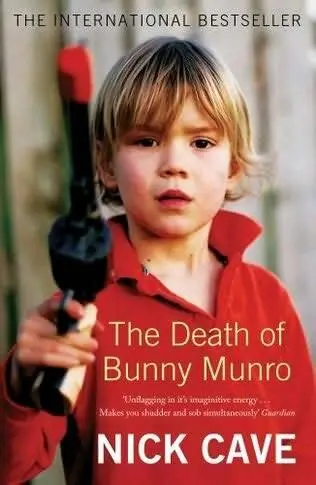

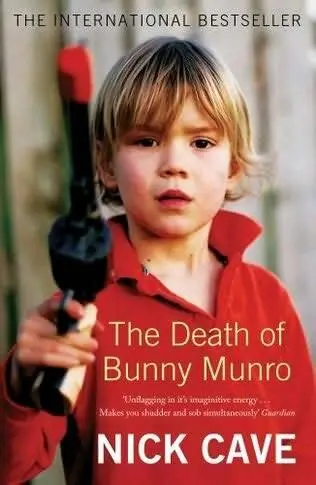

Nick Cave

The Death of Bunny Munro

© 2009

‘I am damned,’ thinks Bunny Munro in a sudden moment of self-awareness reserved for those who are soon to die. He feels that somewhere down the line he has made a grave mistake, but this realisation passes in a dreadful heartbeat, and is gone – leaving him in a room at the Grenville Hotel, in his underwear, with nothing but himself and his appetites. He closes his eyes and pictures a random vagina, then sits on the edge of the hotel bed and, in slow motion, leans back against the quilted headboard. He clamps the mobile phone under his chin and with his teeth breaks the seal on a miniature bottle of brandy. He empties the bottle down his throat, lobs it across the room, then shudders and gags and says into the phone, ‘Don’t worry, love, everything’s going to be all right.’

‘I’m scared, Bunny,’ says his wife, Libby.

‘What are you scared of? You got nothing to be scared of.’

‘Everything, I’m scared of everything ,’ she says.

But Bunny realises that something has changed in his wife’s voice, the soft cellos have gone and a high rasping violin has been added, played by an escaped ape or something. He registers it but has yet to understand exactly what this means.

‘Don’t talk like that. You know that gets you nowhere,’ says Bunny, and like an act of love he sucks deep on a Lambert & Butler. It is in that instance that it hits him – the baboon on the violin, the inconsolable downward spiral of her drift – and he says, ‘Fuck!’ and blows two furious tusks of smoke from his nostrils.

‘Are you off your Tegretol? Libby, tell me you’ve been taking your Tegretol!’

There is silence on the other end of the line then a broken, faraway sob.

‘Your father called again. I don’t know what to say to him. I don’t know what he wants. He shouts at me. He raves,’ she says.

‘For Christ’s sake, Libby, you know what the doctor said. If you don’t take your Tegretol, you get depressed. As you well know, it’s dangerous for you to get depressed. How many fucking times do we have to go through this?’

The sob doubles on itself, then doubles again, till it becomes gentle, wretched crying and it reminds Bunny of their first night together – Libby lying in his arms, in the throes of some inexplicable crying jag, in a down-at-heel hotel room in Eastbourne. He remembers her looking up at him and saying, ‘I’m sorry, I get a little emotional sometimes’ or something like that, and Bunny pushes the heel of his hand into his crotch and squeezes, releasing a pulse of pleasure into his lower spine.

‘Just take the fucking Tegretol,’ he says, softening.

‘I’m scared, Bun. There’s this guy running around attacking women.’

‘What guy?’

‘He paints his face red and wears plastic devil’s horns.’

‘What?’

‘Up north. It’s on the telly.’

Bunny picks up the remote off the bedside table and with a series of parries and ripostes turns on the television set that sits on top of the mini-bar. With the mute button on, he moves through the channels till he finds some black-and-white CCTV footage taken at a shopping mall in Newcastle. A man, bare-chested and wearing tracksuit bottoms, weaves through a crowd of terrified shoppers. His mouth is open in a soundless scream. He appears to be wearing devil’s horns and waves what looks like a big, black stick.

Bunny curses under his breath and in that moment all energy, sexual or otherwise, deserts him. He thrusts the remote at the TV and in a fizz of static it goes out and Bunny lets his head loll back. He focuses on a water stain on the ceiling shaped like a small bell or a woman’s breast.

Somewhere in the outer reaches of his consciousness he becomes aware of a manic twittering sound, a tinnitus of enraged protest, electronic-sounding and horrible, but Bunny does not recognise this, rather he hears his wife say, ‘Bunny? Are you there?’

‘Libby. Where are you?’

‘In bed.’

Bunny looks at his watch, trombones his hand, but cannot focus.

‘For Christ’s sake. Where is Bunny Junior?’

‘In his room, I guess.’

‘Look, Libby, if my dad calls again…’

‘He carries a trident,’ says his wife.

‘What?’

‘A garden fork.’

‘What? Who?’

‘The guy, up north.’

Bunny realises then that the screaming, cheeping sound is coming from outside. He hears it now above the bombination of the air conditioner and it is sufficiently apocalyptic to almost arouse his curiosity. But not quite.

The watermark on the ceiling is growing, changing shape – a bigger breast, a buttock, a sexy female knee – and a droplet forms, elongates and trembles, detaches itself from the ceiling, freefalls and explodes on Bunny’s chest. Bunny pats at it as if he were in a dream and says, ‘Libby, baby, where do we live?’

‘Brighton.’

‘And where is Brighton?’ he says, running a finger along the row of miniature bottles of liquor arranged on the bedside table and choosing a Smirnoff.

‘Down south.’

‘Which is about as far away from “up north” as you can get without falling into the bloody sea. Now, sweetie, turn off the TV, take your Tegretol, take a sleeping tablet – shit, take two sleeping tablets – and I’ll be back tomorrow. Early.’

‘The pier is burning down,’ says Libby.

‘What?’

‘The West Pier, it’s burning down. I can smell the smoke from here.’

‘The West Pier?’

Bunny empties the tiny bottle of vodka down his throat, lights another cigarette, and rises from the bed. The room heaves as Bunny is hit by the realisation that he is very drunk. With arms held out to the side and on tiptoe, Bunny moonwalks across the room to the window. He lurches, stumbles and Tarzans the faded chintz curtains until he finds his balance and steadies himself. He draws them open extravagantly and vulcanised daylight and the screaming of birds deranges the room. Bunny’s pupils contract painfully as he grimaces through the window, into the light. He sees a dark cloud of starlings, twittering madly over the flaming, smoking hulk of the West Pier that stands, helpless, in the sea across from the hotel. He wonders why he hadn’t seen this before and then wonders how long he has been in this room, then remembers his wife and hears her say, ‘Bunny, are you there?’

‘Yeah,’ says Bunny, transfixed by the sight of the burning pier and the thousand screaming birds.

‘The starlings have gone mad. It’s such a horrible thing. Their little babies burning in their nests. I can’t bear it, Bun,’ says Libby, the high violin rising.

Bunny moves back to the bed and can hear his wife crying on the end of the phone. Ten years, he thinks, ten years and those tears still get him – those turquoise eyes, that joyful pussy, ah man, and that unfathomable sob stuff – and he lays back against the headboard and bats, ape-like, at his genitals and says, ‘I’ll be back tomorrow, babe, early.’

‘Do you love me, Bun?’ says Libby.

‘You know I do.’

‘Do you swear on your life?’

‘Upon Christ and all his saints. Right down to your little shoes, baby.’

‘Can’t you get home tonight?’

‘I would if I could,’ says Bunny, groping around on the bed for his cigarettes, ‘but I’m miles away.’

‘Oh, Bunny… you fucking liar…’

The line goes dead and Bunny says, ‘Libby? Lib?’

Читать дальше