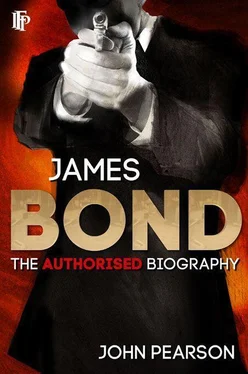

John Pearson - James Bond - The Authorised Biography

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Pearson - James Bond - The Authorised Biography» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, ISBN: 2008, Издательство: Random House, Жанр: Шпионский детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:James Bond: The Authorised Biography

- Автор:

- Издательство:Random House

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:9780099502920

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

James Bond: The Authorised Biography: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «James Bond: The Authorised Biography»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

James Bond: The Authorised Biography — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «James Bond: The Authorised Biography», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But Urquhart had found out about her. She was attractive. Bond had slept with her. And Urquhart discovered something that Bond didn't know. The demure Miss Michel had literary ambitions; and she was more than willing to tell all. The result was that oddity among the James Bond books – The Spy Who Loved Me . Bond says it is the one book he regards with real distaste. Indeed, he feels that he was treated badly over it, and blames Urquhart for getting Fleming involved in the book at a time when he was obviously far from well. (Ian Fleming finally appeared as ‘co-author’ with Vivienne Michel.) Bond says that he was ‘hideously embarrassed by the whole enterprise’.

Certainly one has to sympathize with Bond. Miss Michel's womens’-magazine style revelations would have worried any self-respecting male. For somebody as reticent as Bond these ‘true confession’ type descriptions of the night he spent with the ardent Miss Michel in the Shady Pines Motel must have made quite horrifying reading. Bond says he ‘hit the roof’ when he was finally allowed to see the proofs of the book, but there was nothing he could do except complain to M., and M. dismissed the whole affair as ‘just not worth discussing’. Urquhart had cleverly kept the text away from Bond as long as possible, and as Bond says resignedly, ‘What can one do about that sort of woman?’

In July M. went on holiday. He was no better when he got back – in fact he was quite intolerable, snappy, bad-tempered, getting on everybody's nerves. Even the glacial Miss Moneypenny seemed to be finding him impossible. Bond found her in a state of near prostration after one afternoon non-stop with M. and took her out to dinner. She came gratefully and Bond took her to Alvaro's in the Kings Road, where he thought the pasta was the best in London. Over the spaghetti alle vongole Moneypenny told him all her troubles.

‘I'm really worried for him, James,’ she said. ‘I know he's difficult, but he's never been like this before.’

‘Like what?’ said Bond.

‘Actually losing all control. He's been nagging on at me, and then this afternoon he flew into a rage.’

That cool naval presence in a rage? Bond hadn't thought it possible.

‘What was he like?’ he asked.

‘Terrifying. He started shouting and shoved all the papers off his desk. I simply fled.’

Bond tried hard not to smile at the thought of the stately Moneypenny in precipitate retreat.

‘Perhaps it's the male menopause,’ he said.

‘He should have got over that by now. No, James, the odd thing is that this should have happened after his holiday. He was all right before he went, a little tense and snappy but nothing at all like this.’

‘Any idea what happened on this holiday of his. I don't remember hearing where he went.’

She shook her head. ‘That's the strange thing about it. He was most anxious nobody should know where he was going, and told me to keep it to myself. In fact the forwarding address he left was for a Greek island called Spirellos.’

‘A bit different from his usual fishing trip to the Test,’ said Bond.

‘Perhaps he's in love?’ said Moneypenny, looking suddenly quite gentle.

‘Perhaps he is,’ said Bond. ‘For all our sakes I hope so and the lady soon says yes.’

The idea of M. in love gained credence in the section. It explained everything, and everybody started to make allowances for M.

But as Bond said to Mary Goodnight, ‘She really must be putting the old boy through the hoops. He's getting worse and worse.’

Indeed he was. Bond heard that he was drinking heavily at Blades. And then, the next day, there was a worried telephone call from a friend in the Ministry of Defence.

‘What's the matter with your boss?’

‘What do you mean?’ asked Bond.

‘Yesterday he blew his top at the Joint Chiefs of Staff conference. Nobody knew why. It was most embarrassing. They were discussing possible subversion in the Secret Service, and he suddenly seemed to go berserk. Quite between the two of us, the Chief of G.S. asked me to have a word with you to see if there is anything on the old boy's mind. And could you just keep an eye on him?’

‘You've been pushing him too hard too long,’ Bond replied loyally.

‘Point taken. But that makes it all the more important that there shouldn't be anything unfortunate. We couldn't have the man crack up.’

M. cracking up! The idea was unthinkable. And yet the more Bond thought about it, the more possible it seemed. But what to do? M. was not the sort of man one could invite out for a drink and ask to share his troubles. He was a guarded unforthcoming man and Bond had no idea what went on behind that lined, distinguished-looking face. Nor had he any more idea about his private life. M. kept it rigidly apart from his work. Indeed, the more Bond started thinking about him, the more he realized just how little he knew about this man who ruled his life.

Bond knew he had a house at Windsor, but at that time hadn't been invited there (nor for that matter had anyone else inside the section – M. made no pretence of being hospitable). Nor did Bond know about his friends. He'd never heard of any. It was almost as if M.'s life stopped entirely once his old black Silver Wraith slid away from the Regent's Park Headquarters in the evening. And as Bond realized, he really didn't want to know about M.'s private life.

Fortunately Bill Tanner was now back from hospital (but off all alcohol and almost all the food the canteen had to offer). When Bond discussed the situation with him, he was emphatic that something must be done. But they both realized the problem – how can you start investigating the Head of the Secret Service?

Bond tried to make a start next day. M.'s servant, Chief Petty Officer Hammond was in the office, and Bond made a point of talking to him over coffee in the downstairs canteen. Bond knew he was devoted to M. and was not surprised at the suspicion on his ruddy face as soon as he asked about him.

‘Sir Miles well? I'd say he has his ups and downs like all of us.’

Bond said of course, but recently he'd felt that he was under some sort of quite unusual strain.

‘I couldn't say, Commander Bond. That's not my business.’

Clearly Bond wasn't getting anything from him, but he did his best to tell the Chief Petty Officer that if he did feel anything was wrong with M. he could always get in touch with him or with the Chief of Staff.

‘Thank you, Commander Bond,’ said Hammond loyally.

That same evening, Bond rang Sir James Molony.

‘Trouble with M? No, I've heard nothing, but I hope to God you're wrong. M. is the one man in Britain I'd not take on as a patient if you paid ten times my normal fee.’

Bill Tanner also made inquiries – just as fruitlessly. But Moneypenny was thinking of applying for a transfer, and two days later there was another worried query from Bond's contact in the Ministry of Defence. And then, that evening, Hammond rang Bond at home. He and Mrs Hammond wanted to see him urgently. Bond arranged to meet them in a Windsor tea-shop early next afternoon.

Mrs Hammond was the sort of wife who did the talking. She was a forthright little woman who began by telling the waitress exactly what she thought of her scones and strawberry jam.

‘Now, Commander Bond,’ she said as she condescended to accept a slice of cherry cake, ‘me and my husband are agreed that we should talk to you about Sir Miles, but on condition that not a word of this gets back to him.’

Bond solemnly agreed.

‘For some time now, Sir Miles just hasn't been himself. He's off his food, and he's so snappy with us both.’

Bond made sympathetic noises.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «James Bond: The Authorised Biography»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «James Bond: The Authorised Biography» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «James Bond: The Authorised Biography» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.