The Authorised Biography

Now with updated material by John Battersby

Title Page

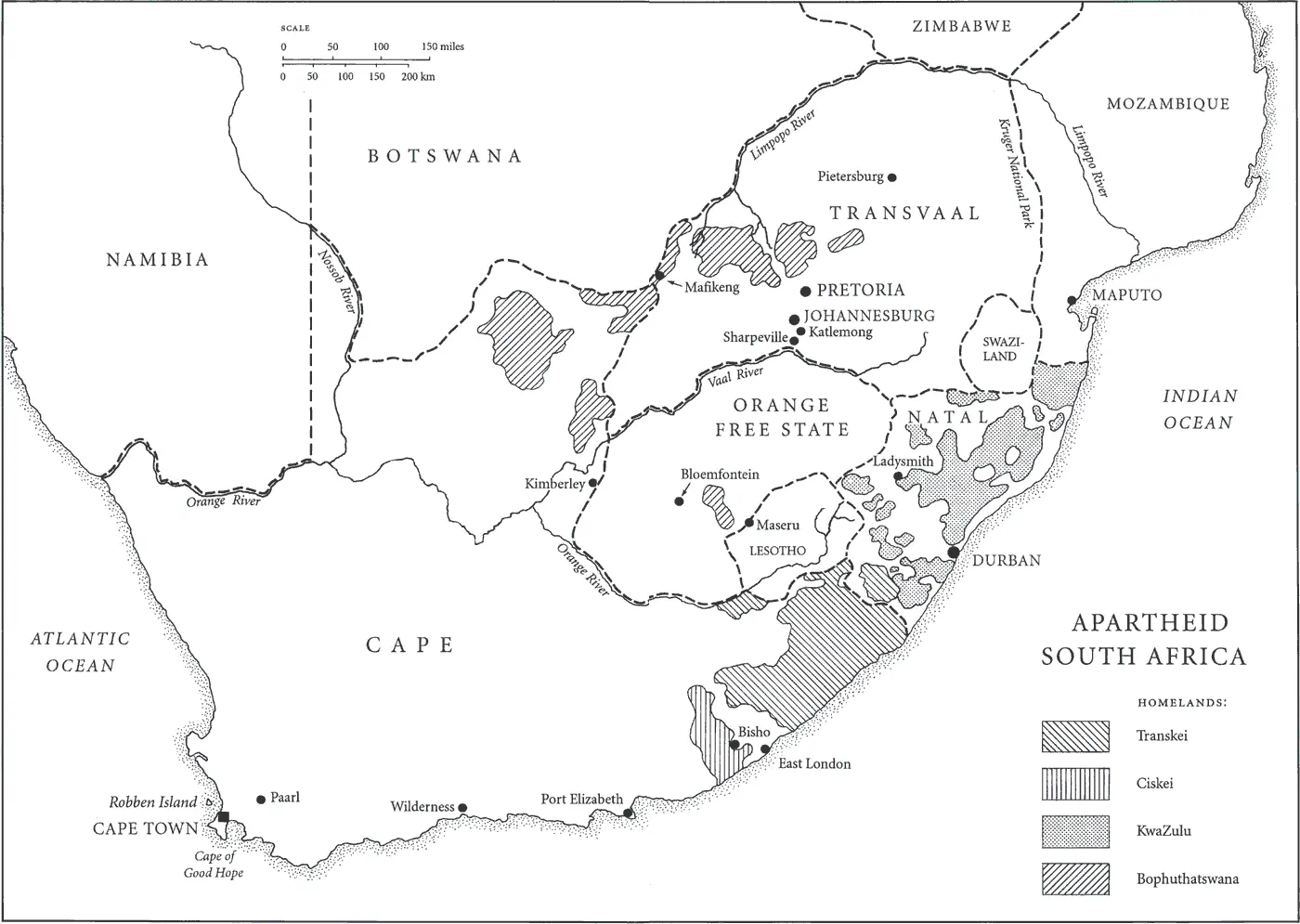

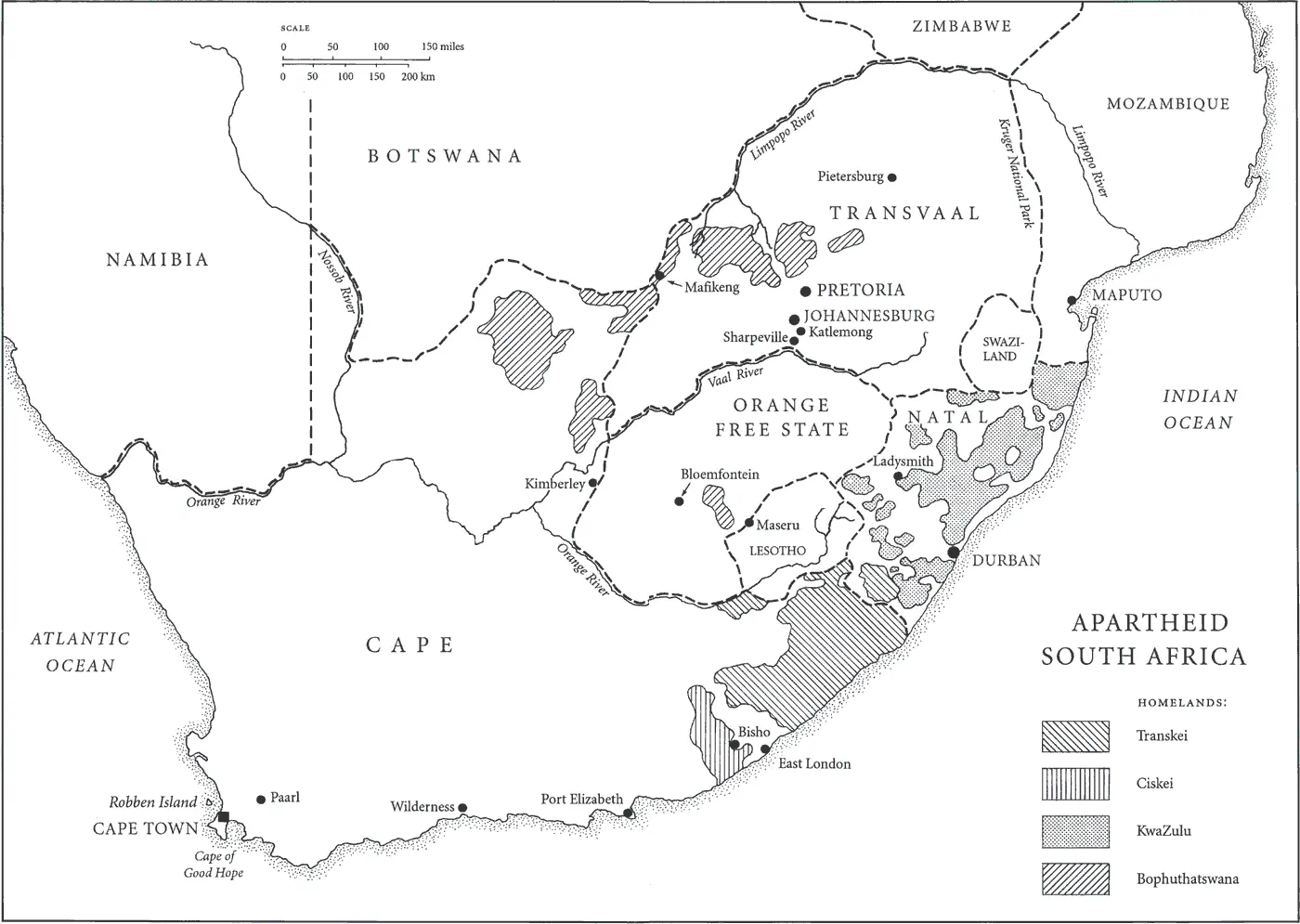

Map: Apartheid South Africa

Introduction

Prologue: The Last Hero

Part I: 1918–1964

1 Country Boy: 1918–1934

2 Mission Boy: 1934–1940

3 Big City: 1941–1945

4 Afrikaners v. Africans: 1946–1949

5 Nationalists v. Communists: 1950–1951

6 Defiance: 1952

7 Lawyer and Revolutionary: 1952–1954

8 The Meaning of Freedom: 1953–1956

9 Treason and Winnie: 1956–1957

10 Dazzling Contender: 1957–1959

11 The Revolution that Wasn’t: 1960

12 Violence: 1961

13 Last Fling: 1962

14 Crime and Punishment: 1963–1964

Part II: 1964–1990

15 Master of my Fate: 1964–1971

16 Steeled and Hardened: 1971–1976

17 Lady into Amazon: 1962–1976

18 The Shadowy Presence: 1964–1976

19 Black Consciousness: 1976–1978

20 Prison Charisma: 1976–1982

21 A Family Apart: 1977–1980

22 Prison Within a Prison: 1978–1982

23 Insurrection: 1982–1985

24 Ungovernability: 1986–1988

25 The Lost Leader: 1983–1988

26 ‘Something Horribly Wrong’: 1987–1989

27 Prisoner v. President: 1989–1990

Part III: 1990–1999

28 Myth and Man

29 Revolution to Cooperation

30 Third Force

31 Exit Winnie

32 Negotiating

33 Election

34 Governing

35 The Glorified Perch

36 Forgiving

37 Withdrawing

38 Graca

39 Mandela’s World

40 Mandela’s Country

41 Image and Reality

Afterword: Living Legend, Living Statue

Source Notes

Select Bibliography

Searchable Terms

About the Author

Praise

Other Books by Anthony Sampson

Copyright

About the Publisher

I am conscious of both the unusual opportunity and the responsibility in undertaking this book. When I wrote to President Mandela in 1995 suggesting an authorised biography he invited me to breakfast in his house in Johannesburg, and told me he would like me to write it because of our long friendship – ‘Provided,’ he joked, ‘that you don’t mention that we first met in a shebeen.’ He reminded me that he had read my book Anatomy of Britain when he was awaiting trial in 1962. He promised to discuss critical questions with me, to try to ensure that the facts were accurate, and to let me see relevant letters and documents. But he would leave me free to make my own judgements and criticisms: it was important, he said, for the movement to learn from mistakes; and, he insisted, ‘I’m no angel.’

It had been my good luck to have first known Mandela in Johannesburg in 1951, and to have seen him at several decisive moments over the next decade before he went to prison. I first encountered him after I had come out to South Africa to edit the black magazine Drum, which opened all doors into the vibrant and exciting world of black writers, musicians and politicians in the Johannesburg in which Mandela moved, and gave me a front seat from which to observe the mounting black opposition to the apartheid government which had come to power in 1948. I attended the ANC conference which approved the Defiance Campaign of 1952; I watched Mandela organising the first volunteers, and mobilising resistance in 1954 to the destruction of Sophiatown, the multi-racial slum where I had spent many happy evenings. In 1957 I saw him frequently at the Treason Trial, about which I later wrote a book; and in 1960, as a correspondent of the Observer, I covered the Sharpeville crisis and interviewed Mandela in Soweto just after the massacre. My last, poignant sight of him was in 1964, when I was observing the Rivonia trial in Pretoria, which gave me a chance to see the final speech he was then preparing (see pp. 192–3). As a journalist I could not see Mandela during his twenty-seven years in prison, but I revisited black South Africa and kept in touch with exiles in London and elsewhere. In the mid-1980s, when the conflict was escalating, I saw much of Oliver Tambo, the ANC President, in London, and arranged meetings for him with British businessmen. I also talked often to Winnie Mandela by telephone. I returned to Johannesburg for the crises of 1985 and 1986, preparing a book about black politics and business, Black and Gold, before the South African government in 1986 banned me from returning. My ban was temporarily lifted just in time for me to return before Mandela’s release from jail in February 1990; later, I visited him twice a week in his Soweto house. Over the next four years I saw him many times, both in London – where he asked me to introduce him at fund-raising receptions – and in Johannesburg, to which I often returned, and where I watched the elections of April 1994.

Since beginning this book I have made several journeys through South Africa with my wife Sally, trying to piece together the jigsaw of Mandela’s varied life, while immersing myself in the fast-changing contemporary scene. I have seen President Mandela in contrasted settings: in his offices and mansions in Pretoria and Cape Town, in his own house in Houghton, on Robben Island, at banquets and conferences, in Parliament in Cape Town, at the UN in New York or at state occasions in London. I have travelled to the Great Place where he was brought up in the Transkei, and to his new house in Qunu. I have talked to scores of his old friends and colleagues, but also to his former opponents, whether warders, officials or political leaders – including ex-President P.W. Botha in Wilderness, ex-President F.W. de Klerk in Cape Town, and the former Foreign Minister Pik Botha in the Transvaal.

Mandela’s moving autobiography Long Walk to Freedom, published in 1994, has provided his own invaluable record of his political development; I have had generous advice from his collaborator Richard Stengel, whose recorded interviews with Mandela have also been useful. I have also been given access to the unpublished memoir which Mandela wrote in jail, and have seen the original manuscript in his own hand. But Mandela’s own autobiography, published when he had first become President, with political discretion and modesty, leaves all the more scope for a many-sided picture which can describe him as others saw him, show how he interacted with friends and enemies, and put his life into a global context.

In writing this book I have tried to show the harsh realities of Mandela’s long and adventurous life as they appeared to him and to his friends at the time, stripped of the gloss of mythology and romance; but also to trace how the glittering image of Mandela was magnified while he was in jail, acquiring its own power and influence across the world; and to show how the prisoner was able to relate the image to reality.

I have given special emphasis to the long years in prison, with the help of extensive interviews, unpublished letters and documents; for Mandela’s prison story has unique value to a biographer, with its human intensity and tests of character, providing an intimate play rather than a wide-ranging pageant; and Mandela’s relationships with his friends and warders became a universal drama, with a significance that transcended African politics. The prison years are often portrayed as a long hiatus in the midst of Mandela’s political career; but I see them as the key to his development, transforming the headstrong activist into the reflective and self-disciplined world statesman.

Читать дальше

![Мик Уолл - Когда титаны ступали по Земле - биография Led Zeppelin[When Giants Walked the Earth - A Biography of Led Zeppelin]](/books/79443/mik-uoll-kogda-titany-stupali-po-zemle-biografiya-thumb.webp)