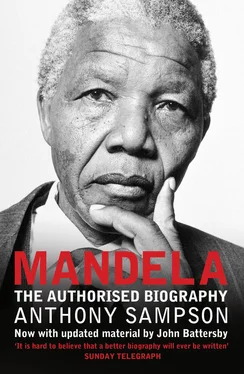

The Regent, Jongintaba, otherwise known as David Dalindyebo, became Mandela’s new father-figure. He was a handsome man, always very well-dressed; Mandela lovingly pressed his trousers, inspiring his lifelong respect for clothes. Jongintaba was a committed Methodist – though he enjoyed his drink – and prayed every day at the nearby church run by his relative the Reverend Matyolo. His son Justice, four years Mandela’s elder, was to be his role model for the next decade, the ideal of worldly prowess and elegance, as sportsman, dandy and ladies’ man. Justice was an all-rounder, excelling in team sports like cricket, soccer and rugby. Mandela, less well co-ordinated, made his mark in more rugged and individual sports like boxing and long-distance running. A photograph shows Justice as bright-eyed, confident and combative, while the young Mandela was less assertive, and strove to acquire Justice’s assurance. Justice was after all the heir to the chieftaincy, while Mandela depended on the Regent’s favours.

Mandela loved the country pleasures at Mqhekezweni, which were more numerous in those days than they are now, and included riding horses and dancing to the tribal songs of Xhosa girls (how different, he reflected in jail, from his later delight in Miriam Makeba, Eartha Kitt or Margot Fonteyn). But Mandela was also more serious and harder-working than the other boys. He thrived at the local mission school, where he began to learn English from Chambers’ English Reader, writing on a slate and speaking the words carefully, with a slow formality and the local accent which never left him.

Whites were hardly visible at Mqhekezweni, except for occasional passers-by. Mandela’s sister Mabel remembers being impressed when he and his schoolfriends met a white man who needed help because his motorbike had broken down, and Mandela was able to speak to him in English. 11But Mabel could also be quite frightened of Mandela: ‘He didn’t like to be provoked. If you provoked him he would tell you directly … He had no time to fool around. We could see he had leadership qualities.’ 12

A crucial part of Mandela’s education lay in observing the Regent. He was fascinated by Jongintaba’s exercise of his kingship at the periodic tribal meetings, to which Tembu people would travel scores of miles on foot or on horseback. Mandela loved to watch the tribesmen, whether labourers or landowners, as they complained candidly and often fiercely to the Regent, who listened for hours impassively and silently, until finally at sunset he tried to produce a consensus from the contrasting views. Later, in jail, Mandela would reflect:

One of the marks of a great chief is the ability to keep together all sections of his people, the traditionalists and reformers, conservatives and liberals, and on major questions there are sometimes sharp differences of opinion. The Mqhekezweni court was particularly strong, and the Regent was able to carry the whole community because the court was representative of all shades of opinion. 13

As President, Mandela would seek to reach the same kind of consensus in cabinet; and he would always remember Jongintaba’s advice that a leader should be like a shepherd, directing his flock from behind by skilful persuasion: ‘If one or two animals stray, you go out and draw them back to the flock,’ he would say. ‘That’s an important lesson in politics.’ 14

Mandela was brought up with the African notion of human brotherhood, or ‘ubuntu’, which described a quality of mutual responsibility and compassion. He often quoted the proverb ‘Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu,’ which he would translate as ‘A person is a person because of other people,’ or ‘You can do nothing if you don’t get the support of other people.’ This was a concept common to other rural communities around the world, but Africans would define it more sharply as a contrast to the individualism and restlessness of whites, and over the following decades ubuntu would loom large in black politics. As Archbishop Tutu defined it in 1986: ‘It refers to gentleness, to compassion, to hospitality, to openness to others, to vulnerability, to be available to others and to know that you are bound up with them in the bundle of life.’ 15

Mandela regarded ubuntu as part of the general philosophy of serving one’s fellow men. From his adolescence, he recalled, he was viewed as being unusually ready to see the best in others. To him this was a natural inheritance: ‘People like ourselves brought up in a rural atmosphere get used to interacting with people at an early age.’ But he conceded that, ‘It may be a combination of instinct and deliberate planning.’ In any case, it was to become a prevailing principle throughout his political career: ‘People are human beings, produced by the society in which they live. You encourage people by seeing good in them.’ 16

Mandela’s admiration for tribal traditions and democracy was reinforced by the Xhosa history that he picked up from visiting old chiefs and headmen. Many of them were illiterate, but they were masters of the oral tradition, declaiming the epics of past battles like Homeric bards. The most vivid story-teller, Chief Joyi, like Mandela a descendant of the great King Ngubengcuka, described how the unity and peace of the Xhosa people had been broken by the coming of the white men, who had divided them, dispossessed them and undermined their ubuntu. 17Mandela would often look back to this idealised picture of African tribal society. He described it in a long speech in 1962, shortly before he began his prison sentence:

Then our people lived peacefully, under the democratic rule of their kings and their amapakati, and moved freely and confidently up and down the country without let or hindrance. Then the country was ours, in our own name and right. We occupied the land, the forests, the rivers; we extracted the mineral wealth below the soil and all the riches of this beautiful country. We set up and operated our own government, we controlled our own armies and we organised our own trade and commerce.

It was, in his eyes, a golden age without classes, exploitation or inequality, in which the tribal council was a model of democracy:

The council was so completely democratic that all members of the tribe could participate in its deliberations. Chief and subject, warrior and medicine man, all took part and endeavoured to influence its decisions. It was so weighty and influential a body that no step of any importance could ever be taken by the tribe without reference to it. 18

The history of the Xhosas was very much alive when Mandela was a child, and old men could remember the time when they were still undefeated. The pride and autonomy of the Transkei and its Xhosa-speaking tribes – the Tembus, the Pondos, the Fingoes and the Xhosas themselves – had survived despite the humiliations of conquest and subjection over the previous century. Some Xhosas had intermarried with other peoples, including the Khoikhoi (called ‘Hottentots’ by white settlers), which helped to give a wide variety to their physical features: Mandela’s own distinctive face, with his narrow eyes and strong cheekbones, has sometimes been explained by Khoikhoi blood. 19But the Xhosas retained their distinctive culture and language. Many white colonists who first encountered them in the late eighteenth century were impressed by their physique, their light skin and sensitive faces, and their democratic system of debate and government: ‘They are equal to any English lawyers in discussing questions which relate to their own laws and customs,’ wrote the missionary William Holden in 1866. In the 1830s the British Commander Harry Smith called the Xhosa King Hintsa ‘the very image of poor dear George IV’. 20But, over the course of a hundred years and nine Xhosa wars, the British forces moving east from the Cape gradually deprived the Xhosas of their independence and their land. By 1835 Harry Smith had crossed the river Kei to begin the subjugation of the Transkei. By 1848 he had imposed his own English system on the Xhosa chiefs, informing them that their land ‘shall be divided into counties, towns and villages, bearing English names. You shall all learn to speak English at the schools which I shall establish for you … You may no longer be naked and wicked barbarians which you will ever be unless you labour and become industrious.’ 21In the eighth Xhosa war in 1850 the British Army – after setbacks which strained it to its limit and atrocities committed by both sides – drove the Xhosa chiefs out of their mountain fastnesses and firmly occupied ‘British Kaffraria’, later called the Ciskei. The Tembu chiefs who ruled the southern part of the Transkei had been relatively unscathed by the earlier wars, but now they were subjugated and sent to the terrible prison on Robben Island, just off the coast from Cape Town, which became notorious in Xhosa folklore.

Читать дальше

![Мик Уолл - Когда титаны ступали по Земле - биография Led Zeppelin[When Giants Walked the Earth - A Biography of Led Zeppelin]](/books/79443/mik-uoll-kogda-titany-stupali-po-zemle-biografiya-thumb.webp)