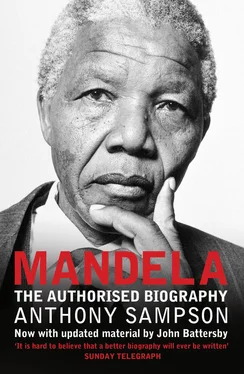

After this humiliation and impoverishment, in 1856 the Xhosas accomplished their own self-destruction. A young prophetess, Nongqawuse, told them to kill all their cattle and to prepare for a resurrection. As a result, over half the population of the Ciskei starved to death. By the end of the ninth Xhosa war in 1878 the two chief houses of the Xhosa people, the Ngqika and the Gcaleka, had been subjugated and were forced into a new exodus across the Kei. Successive leaders were sent to Robben Island, in keeping with the order of Sir George Grey, the Governor of the Cape, ‘for the submission of every chief of consequence; or his disgrace if he were obdurate’. 22

It was not till 1894 that Pondoland, in the northern part of the Transkei, came under the Cape administration. But after the Union of South Africa came into being in 1910, the Xhosas faced growing controls by white magistrates. The whites, as Mandela came to see it, captured the institution of the chieftaincy, and ‘used it to suppress the aspirations of their own tribesmen. So they almost destroyed the chieftaincy.’ 23

In the later nineteenth century the Zulus, the other major tribal power to the north, became more famous among whites and foreigners as ruthless fighters than the Xhosas, particularly the Zulu warrior-king Shaka, who had set out to conquer and unify all the southern tribes in the 1820s. The Zulus attracted the admiration of many British churchmen, including the dissident Bishop John William Colenso of Natal; but they acquired unique military fame in January 1879 when the British provoked a war with Shaka’s successor Cetewayo, whose army completely destroyed a British force of 1,200 at the battle of Isandhlwana. When the British sent out reinforcements they included the Prince Imperial, son of Louis Napoleon, who was ambushed and speared to death by Zulu assegais. (‘A very remarkable people the Zulus,’ said Disraeli. ‘They defeat our generals, they convert our bishops, they have settled the fate of a great European dynasty.’ 24) The humiliation of Isandhlwana was finally avenged in July when the British crushed Cetewayo at the battle of Ulundi and subjugated the Zulus; but their reputation for fighting spirit remained.

The Xhosa chiefs appeared less martial and intransigent than the Zulus, and after the Xhosa wars they seemed defeated and demoralised – sometimes with the help of alcohol. But out of the desolation of the Xhosa wars another tradition was growing up, that of mission schools and Christian culture, which gradually produced a new Xhosa elite of disciplined, well-educated young men and women. While embracing Western ideas, they still aspired to restore the rights and dignity of their own people. The British liberal tradition was reasserting itself in the Cape, with the expansion of the mission stations and the introduction of a qualified vote for blacks. Educated young Xhosas were exploiting the aptitude for legal argument, analysis and debate which early white visitors had observed. It was a route that would in time lead some of them into the political campaigns of the black opposition in the 1960s – sometimes called the tenth Xhosa war – and, like their predecessors, to Robben Island; but they would win their battle, and not through military might, but through their skills in argument and reasoning.

Like other conquered peoples such as the Scots or the American Indians, the Xhosas retained their own version of history which, being largely oral, was easily ignored by the outside world. ‘The European insisted that we accept his version of the past,’ said Z.K. Matthews, the African professor who would teach Mandela. But ‘it was utterly impossible to accept his judgements on the actions and behaviour of Africans, of our own grandfathers in our own lands’. 25Mandela, despite all his Western education, would always champion oral historians, and would continue to be inspired by the spoken stories of the Xhosas which he had heard from his elders: ‘I knew that our society had produced black heroes and this filled me with pride: I did not know how to channel it, but I carried this raw material with me when I went to college.’ 26While most white historians regarded the Xhosa rebellions as firmly placed in the past, overlaid by the relentless logic of Western conquest and technology, Mandela, like other educated Xhosas, saw the white occupation as a recent interlude, and would never forget that his great-grandfather ruled a whole region a century before he was born.

1934–1940

IN 1934, when he was sixteen, Mandela went with twenty-five other Tembu boys, led by the Regent’s son Justice, to an isolated valley on the banks of the Bashee river, the traditional setting for the circumcision of future Tembu kings. No rural Xhosa could take office without this ritual. Mandela would vividly remember the ceremony which marked the coming of manhood: the days spent beforehand with the other boys in the ‘seclusion lodges’; singing and dancing with local women on the night before the ceremony; bathing in the river at dawn; parading in blankets before the elders and the Regent himself, who watched the boys to see that they behaved with courage.

The old circumcisor (incibi) appeared with his assegai, and when their turn came the boys had to cry out ‘I am a man!’ 1Mandela was tense and anxious, and when the assegai cut off his foreskin he remembered it as feeling like molten lead flowing through his veins. He briefly forgot his words as he pressed his head into the grass, before he too shouted out, ‘I am a man!’ But he was conscious that he was not naturally brave: ‘I was not as forthright and strong as the other boys.’ 2

After the ceremony was over, when they had buried their foreskins, covered their faces in white ochre and then washed it off in the river, Mandela was proud of his new status as a man, with a new name – Dalibunga, meaning the founder of the council – who could walk tall and face the challenges of life. He still felt himself to be part of a proud tribe, and was shocked when Chief Meligqili told the boys that they would never really be men because they were a conquered people who were slaves in their own country. 3It was not until ten years later that Mandela would recognise that chief as the forerunner of brave politicians like Alfred Xuma and Yusuf Dadoo, James Phillips and Michael Harmel. In the meantime he would take great pride in his circumcised manliness and the superiority it implied; at university he was shocked to learn that one of his friends had not been circumcised. Only when he later became immersed in politics in Johannesburg did he, as he put it, ‘crawl out of the prejudice of my youth and accept all people as equals’. 4

Mandela soon had to make a more fundamental social transition – into the midst of a rigorous missionary schooling. The Regent was determined to have him properly educated, as a prospective counsellor to Sabata, the future king, so he sent him to board at the great Methodist institution of Clarkebury, across the Bashee river, which had educated both the Regent and his son Justice, and would educate Sabata. For the Tembu royal family Clarkebury had a special resonance: it was founded in 1825, when King Ngubengcuka, Mandela’s great-grandfather, had met the pioneering Methodist William Shaw and promised to give him land to set up a mission. 5The station was duly founded by the Reverend Richard Haddy, some miles from the king’s Great Place, and named in honour of a distinguished British theologian, Dr Adam Clarke.

The Methodists were the most adventurous and influential of the missionaries who had penetrated the Eastern Cape at the same time as the British armies – sometimes in league with them, sometimes at odds. To many Xhosa patriots missionaries were essentially the agents of British governments, who used them to divide and disarm the rival chiefs: the Trotskyist writer ‘Nosipho Majeke’ wrote in 1952 that the Wesleyan missions were ‘ready at all times to co-operate with the Government’, and were able to surround the great King Hintsa, turning other chiefs against him. 6But the mission teachers were frequently in opposition to white administrations, and played an independent role in the development of the Xhosa people. By 1935 the mission schools throughout South Africa registered 342,181 African pupils, and as the historian Leonard Thompson records, they ‘reached into every African reserve community’. 7

Читать дальше

![Мик Уолл - Когда титаны ступали по Земле - биография Led Zeppelin[When Giants Walked the Earth - A Biography of Led Zeppelin]](/books/79443/mik-uoll-kogda-titany-stupali-po-zemle-biografiya-thumb.webp)