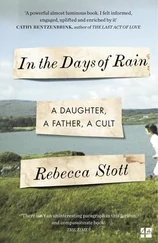

1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...21 The Methodism of Healdtown and Clarkebury did not make a deep religious impact on Mandela. He would never be a true believer, although many of his later friends, including his present wife, were educated by Methodists. But he would always be influenced by the schools’ puritanical atmosphere, the strict discipline and mental training, the Wesleyan emphasis on paring down ideas to their bare essentials, avoiding frills and distractions. He would always disapprove of heavy drinking or swearing; and the self-reliance in these boarding-school surroundings would add to his fortitude.

Mandela was immersed not just in Methodism, but in British history and geography. ‘As a teenager in the countryside I knew about London and Glasgow as much as I knew about Cape Town and Johannesburg,’ he would recall from jail fifty years later, writing to the Provost of Glasgow and mentioning Scots patriots like William Wallace, Robert the Bruce and the Earl of Argyll. 25But he was resistant to becoming a ‘black Englishman’, and took great pride in his own Xhosa culture, encouraged by his history teacher, the much-liked Weaver Newana, who added his own oral history to the accounts of the Xhosa wars already familiar to the boy. Mandela won the prize for the best Xhosa essay in 1938; and he was thrilled when the famous Xhosa poet Krune Mkwayi visited the college, appearing in a kaross of hide, with two spears, to recite his dramatic poems in praise of the Xhosas.

Mandela made close friendships with several Xhosa boys who subsequently joined the ANC, including Jimmy Njongwe, with whom he later ‘starved and suffered in Johannesburg’, and who became a doctor and later a key organiser of the Defiance Campaign. 26He also made friends outside his tribe among Sotho-speakers like Zachariah Molete, who later befriended him in Alexandra township in Johannesburg, and the zoology teacher Frank Lebentlele. 27Mandela was much impressed by another Sotho-speaker, his housemaster the Reverend Seth Mokitimi, who later became the first black president of the Methodist Church; Mokitimi pushed through reforms to give students more freedom and better food. 28

The white teachers at Healdtown kept aloof from the black teachers, eating separately: one even had to resign after other teachers complained that he was fraternising with blacks. ‘What a racist place Healdtown was and continued to be!’ wrote Phyllis Ntantala, who was a student till 1935, and whose son Pallo Jordan would later join Mandela’s cabinet. 29A few of the younger white teachers, though, were beginning to make friends with black colleagues and some students. 30Like Clarkebury, the school was co-educational, but girls and boys were strictly separated outside the schoolrooms, and could be expelled for talking to each other. By 1935, however, the Reverend Mokitimi had instituted mixed dinners every Sunday, where girls and boys sat together wearing their best clothes. The more sophisticated and prosperous students loved to show off: as Phyllis Ntantala wrote, ‘They went to those dinners dressed to kill.’ 31But for those from simpler homes the European etiquette of knives and forks was a strain. Mandela recalled: ‘We left the table hungry and depressed.’ 32

The Duke and his white staff had little sense that they were educating future black leaders. They were exasperated by the students’ periodic protests and strikes, usually starting over the poor food, but which they suspected were really based on conflicts between tribes, or between town and country. In 1936 there were more serious political protests when the government’s new ‘Hertzog Bills’ removed blacks from the common voters’ roll and abolished the title deeds of the local Fingo people, who were in turn disillusioned by the failure of the missionary staff to defend their interests. 33But Mandela was only vaguely aware of black politics. At Healdtown he first heard about the African National Congress, which was set up in 1912; the Tembu king had paid thirty cattle to enrol his own tribe in it. Yet to Mandela ‘it was something vague located in the distant past’. 34The mission teachers were inclined to ascribe any political protests to ‘agitators’ stirred up by communism, and most saw themselves as educating a small elite who were quite different from ordinary blacks: as one envious government official explained to them, they were dealing with the layer of fertile soil on top, while he dealt with the hard rock which was impervious to change. 35

Mandela was still torn between the two aspects of the British presence in South Africa: the brutal military subjugation of the Xhosas and the enlightened influence of liberal English education. This contradiction had been summed up in a poem, ‘The Prince of Britain’, by Mandela’s favourite poet Mkwayi, written to celebrate the visit of the Prince of Wales to the Ciskei in 1925:

You sent us the truth, denied us the truth;

You sent us the life, deprived us of life;

You sent us the light, we sit in the dark,

Shivering, benighted in the bright noonday sun. 36

Mandela graduated from Healdtown in 1938, and the next year went on to the university at Fort Hare, a few miles from Healdtown and a mile from the great missionary school of Lovedale, to which it was linked. The Regent bought him a three-piece suit: ‘We thought there could never be anyone smarter than him at Fort Hare,’ said Mandela’s cousin Ntombizodwa. 37

The ‘South African Native College’ at Fort Hare was a tiny black university, the only one in South Africa, but it was destined to be a seedbed of the revolution that followed. In 1939 it was only twenty-three years old, having been set up, surprisingly, in the midst of the First World War, and opened by the Prime Minister Louis Botha himself. The first principal, Alexander Kerr, suspected that Botha had regarded it as a sop, a gesture to the blacks in wartime, when the whites feared ‘native trouble’. But after white governments hardened their attitudes to blacks in the 1920s, the anomaly of its existence was even more remarkable. 38The later Prime Minister General Jan Smuts worried little about its revolutionary potential; he viewed Fort Hare in the context of his policy of trusteeship. When he addressed the university’s graduates in 1938, the year before Mandela arrived, he argued: ‘The Europeans have come here as the bearers of the higher culture. They have been in some sense a missionary race, but if salvation is ever to come to the native peoples of South Africa it will finally have to come from themselves.’ 39

The university’s start had been very modest, with twenty students preparing for matriculation (the first four candidates all failed). 40When Mandela arrived there were still fewer than two hundred students (of whom sixty-seven were Xhosa-speaking), including ten Indians and sixteen Coloureds. 41But the influence of Fort Hare already went far beyond its student numbers. Supported by the surrounding schools, it had become the focus for the intellectual elite of black South Africans. Its student body was both aristocratic and meritocratic, bringing together royal and mission families. It had been founded not only by white missionaries but by black educationalists from pioneering mission families, including the Jabavus, the Makiwanes and the Bokwes, all of whom were linked by marriage. The great teacher John Tengo Jabavu, editor of the black newspaper Imvo, was a promoter of Fort Hare: his son ‘Jili’ was its first black professor, and married the daughter of the Reverend Tennyson Makiwane. Jili Jabavu was later joined as professor by Z.K. Matthews, the son of a Kimberley miner, who had become the first graduate of Fort Hare; he called himself ‘a new specimen in the zoo of African mankind’. 42Matthews in turn married Frieda Bokwe, the sister of his college friend Rosebery Bokwe, from another prominent mission family.

Читать дальше

![Мик Уолл - Когда титаны ступали по Земле - биография Led Zeppelin[When Giants Walked the Earth - A Biography of Led Zeppelin]](/books/79443/mik-uoll-kogda-titany-stupali-po-zemle-biografiya-thumb.webp)