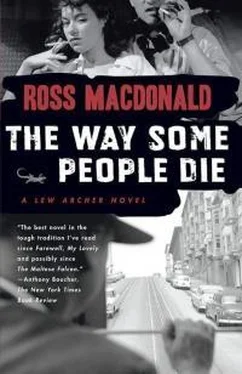

Росс Макдональд - The Way Some People Die

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Росс Макдональд - The Way Some People Die» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Way Some People Die

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Way Some People Die: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Way Some People Die»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The third Lew Archer mystery, in which a missing-persons search takes him "through slum alleys to the luxury of a Palm Springs resort, to a San Francisco drug-peddler's shabby room. Some of the people were dead when he reached them. Some were broken. Some were vicious babes lost in an urban wilderness.

The Way Some People Die — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Way Some People Die», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“That’s Joe,” he said finally. “Was there any doubt about it?”

“We like to have a relative, just to make it legal.” Callahan had removed his hat and assumed an expression of solemnity.

Mrs. Tarantine had been silent, her broad face almost impassive. She cried out now, as if the fact had sunk through layers of flesh to her quick: “Yes! It is my son, my Guiseppe. Dead in his sins. Yes!” Her great dark eyes were focused for distance. She saw the dead man lying far down in hell.

Mario glanced at Callahan in embarrassment, and jerked at his mother’s arm. “Be quiet, Mama.”

“Look at him!” she cried out scornfully. “Too smart to go to Mass. For many years no confession. Now look at my boy, my Guiseppe. Look at him, Mario.”

“I already did,” he said between his teeth. He pulled at her roughly. “Come away now.”

She laid one arm across the dead man’s waist to anchor herself. “I will stay here, with Guiseppe. Poor baby.” She spoke in Italian to the dead man, and he answered her with silence.

“You can’t do that, Mrs. Tarantine.” Callahan rocked in pain from one foot to the other. “The doctor’s going to perform an autopsy, you wouldn’t want to see it. You don’t object, do you?”

“Naw, she don’t object. Come on, Mama, you get yourself all dirty.”

She allowed herself to be drawn towards the door. Mario paused in front of me: “What do you want?”

“I’ll drive you home if you like.”

“We’re riding with the chief deputy. He wants to ask me some questions, he says.”

The mother looked at me as if I was a shadow on the wall. There was a stillness in her to match the stillness of the dead.

“Answer a couple for me.”

“Why should I?”

I moved up close to him: “You want me to tell you in Mexican?”

His attempt to smile when he got it was grotesque. He shot a nervous glance at Callahan, who was crossing the room towards us. “Okay, Mr. Archer. Shoot.”

“When did you see your brother last?”

“Friday night, like I told you.”

“Are those the clothes he was wearing?”

“Friday night, you mean? Yeah, those are the same clothes. I wouldn’t be sure it was him if it wasn’t for the clothes.”

Callahan spoke up behind him: “There’s no question of identification. You recognize your son, don’t you, Mrs. Tarantine?”

“Yes,” she said in a deep voice. “I know him. I ought to know him, the boy I nursed from a little baby.” Her hands moved on her black silk expanse of bosom.

“That’s fine – I mean, thank you very much. We appreciate you coming down here and all.” With a disapproving glance at me, Callahan ushered them out.

He turned to me when they were out of earshot: “What’s eating you? I knew the guy, knew him well enough not to grieve over him. His mother and his brother certainly knew him.”

“Just an idea I had. I like to be sure.”

“Trouble with you private dicks,” he grumbled, “you’re always looking for an angle, trying to find a twist in a perfectly straight case.”

Chapter 32

An inner door opened, and a plump coatless man in a striped shirt appeared in the opening. “Telephone for you,” he said to Callahan. “It’s your office calling.” He had an undertaker’s soft omniscient smile.

“Thanks,” Callahan said as he passed him in the doorway.

The man in the striped shirt moved like a wingless moth toward the lighted table. His bright black boots hissed on the concrete floor.

“Well,” he said to the dead man, “you aren’t as pretty as you might be, are you? When doctor’s through with you, you won’t be pretty in the least. However, we’ll fix you up, I give you my word.” His voice dripped in the stillness like syrup made from highly refined sugar.

I stepped outside and closed the door and lit a cigarette. It was half burned down when Callahan reappeared. He was bright-eyed, and his cheeks had a rosy shine.

“What have you been doing, drinking embalming fluid?”

“Teletype from Los Angeles. Keep it to yourself, and I’ll let you in on it.” I couldn’t have prevented him from telling me. “They raided the Dowser mob – Treasury agents and D. A.’s men. Caught them with enough heroin to give the whole city a jag.”

“Any casualties?” I was thinking of Colton.

“Not a one. They came in quiet as lambs. And get this: Tarantine worked for the corporation, he fronted for Dowser down at the Arena right here in town. You were looking for an angle, weren’t you? There it is.”

“Fascinating,” I said.

A car came up the driveway, turned the corner of the building and parked beyond the canopy. A slope-shouldered man with a medical bag climbed out.

“Sorry I’m so late,” he said to Callahan. “It was a slow delivery, and then I snatched some supper.”

“The customer’s still waiting.” He turned to me. “This is Dr. McCutcheon. Mr. Archer.”

“How long will it take?” I asked the doctor.

“For what?”

“To determine the cause of death.”

“An hour or two. Depends on the indications.” He glanced inquiringly at Callahan: “I understand he was drowned.”

“Yah, we thought so. Could be a gang murder, though,” Callahan added knowingly. “He ran with the Dowser gang.”

“Take a good look for anything else that might have caused his death,” I said. “If you don’t mind my shoving an oar in.”

He shook his tousled gray head impatiently. “Such as?”

“I wouldn’t know. Blunt instrument, hypo, even a bullet wound.”

“I always make a thorough examination,” McCutcheon stated. Hint ended the conversation.

I left my car parked in front of (he mortuary and walked the two blocks to the main street. I was hungry in spite of the odors that seemed to have soaked into my clothes, of fish and kelp and disinfected death. In spite of the questions asking themselves like a quiz program tuned in to my back fillings, with personal comments on the side.

Callahan had recommended a place called George’s Cafe . It turned out to be a restaurant-bar, lower-middle-class and middle-aged. A bar ran down one side, with a white-capped short-order cook at a gas grill that crowded the front window. There were booths along the other side, and a row of tables covered with red-checked tablecloths down the center. Three or four ceiling fans turned languidly, mixing the smoky air into a uniform blue-gray blur. Everything in the place, including the customers phalanxed at the bar, had the air of having been there for a long time.

As soon as I sat down in one of the empty booths, I felt that way myself. The place had a cozy subterranean quality, like a time capsule buried deep beyond the reach of change and violence. The fairly white-coated waiters, old and young, had a quick slack economy of movement surviving from a dead regretted decade. The potato chips that came with my sizzling steak tasted exactly the same as the chips I ate out of greasy newspaper wrappings when I was in grade school in Oakland in 1920. The scenic photographs that decorated the walls – Route of the Union Pacific – reminded me of a stereopticon I had found in my mother’s great-aunt’s attic. The rush and whirl of bar conversation sounded like history.

I was finishing my second bottle of beer when I caught sight of Galley through the foam-etched side of the glass. She was standing just inside the door, poised on high heels. She had on a black coat, a black hat, black gloves. For an instant she looked unreal, a ghost from the present. Then she saw me and moved toward me, and it was everything else that seemed unreal. Her vitality blew her along like a strong wind. Yet her face was haggard, as if her vitality was something separate from her, feeding on her body.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Way Some People Die»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Way Some People Die» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Way Some People Die» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.