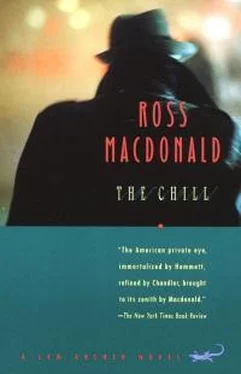

Ross Macdonald

THE CHILL

1964

The people and institutions in this novel are all imaginary, and do not refer to any actual people or institutions.

R. M.

The heavy red-figured drapes over the courtroom windows were incompletely closed against the sun. Yellow daylight leaked in and dimmed the electric bulbs in the high ceiling. It picked out random details in the room: the glass water cooler standing against the paneled wall opposite the jury box, the court reporter’s carmine-tipped fingers playing over her stenotype machine, Mrs. Perrine’s experienced eyes watching me across the defense table.

It was nearly noon on the second and last day of her trial. I was the final witness for the defense. Her attorney had finished questioning me. The deputy D.A. waived cross-examination, and several of the jurors looked at him with puzzled frowns. The judge said I could go.

From my place on the witness stand I’d noticed the young man sitting in the front row of spectators. He wasn’t one of the regular trial-watchers, housewives and pensioners filling an empty morning with other people’s troubles. This one had troubles of his own. His brooding blue gaze stayed on my face, and I had the uncomfortable feeling that he might be willing to share his troubles with me.

He rose from his seat as I stepped down and intercepted me at the door. “Mr. Archer, may I talk to you?”

“All right.”

The bailiff opened the door and gestured urgently. “Outside, gentlemen. Court is still in session.”

We moved out into the corridor. The young man scowled at the automatically closing door. “I don’t like being pushed around.”

“I’d hardly describe that as being pushed around. What’s eating you, friend?”

I shouldn’t have asked him. I should have walked briskly out to my car and driven back to Los Angeles. But he had that clean, crewcut All-American look, and that blur of pain in his eyes.

“I just got thrown out of the Sheriff’s office. It came on top of a couple of other brushoffs from the local authorities, and I’m not used to that kind of treatment.”

“They don’t mean it personally.”

“You’ve had a lot of detective experience, haven’t you? I gathered that from what you said on the witness stand. Incidentally, you did a wonderful job for Mrs. Perrine. I’m sure the jury will acquit her.”

“We’ll see. Never bet on a jury.” I distrusted his compliment, which probably meant he wanted something more substantial from me. The trial in which I had just testified marked the end of a long uninteresting case, and I was planning a fishing trip to La Paz. “Is that all you wanted to say to me?”

“I have a lot to say, if you’ll only listen. I mean, I’ve got this problem about my wife. She left me.”

“I don’t ordinarily do divorce work, if that’s what you have in mind.”

“Divorce?” Without making a sound, he went through the motions of laughing hollowly, once. “I was only married one day – less than one day. Everybody including my father keeps telling me I should get an annulment. But I don’t want an annulment or a divorce. I want her back.”

“Where is your wife now?”

“I don’t know.” He lit a cigarette with unsteady hands. “Dolly left in the middle of our honeymoon weekend, the day after we were married. She may have met with foul play.”

“Or she may have decided she didn’t want to be married, or not to you. It happens all the time.”

“That’s what the police keep saying: it happens all the time. As if that’s any comfort! Anyway, I know that wasn’t the case. Dolly loved me, and I loved – I love her.”

He said this very intensely, with the entire force of his nature behind the words. I didn’t know his nature but there was sensitivity and feeling there, more feeling than he could handle easily.

“You haven’t told me your name.”

“I’m sorry. My name is Kincaid. Alex Kincaid.”

“What do you do for a living?”

“I haven’t been doing much lately, since Dolly – since this thing happened. Theoretically I work for the Channel Oil Corporation. My father is in charge of their Long Beach office. You may have heard of him. Frederick Kincaid?”

I hadn’t. The bailiff opened the door of the courtroom, and held it open. Court had adjourned for lunch, and the jurors filed out past him. Their movements were solemn, part of the ritual of the trial. Alex Kincaid watched them as if they were going out to sit in judgment on him.

“We can’t talk here,” he said. “Let me buy you lunch.”

“I’ll have lunch with you. Dutch.” I didn’t want to owe him anything, at least till I’d heard his story.

There was a restaurant across the street. Its main room was filled with smoke and the roar of conversation. The red-checkered tables were all occupied, mainly with courthouse people, lawyers and sheriff’s men and probation officers. Though Pacific Point was fifty miles south of my normal beat, I recognized ten or a dozen of them.

Alex and I went into the bar and found a couple of stools in a dim corner. He ordered a double scotch on the rocks. I went along with it. He drank his down like medicine and tried to order a second round immediately.

“You set quite a pace. Slow down.”

“Are you telling me what to do?” he said distinctly and unpleasantly.

“I’m willing to listen to your story. I want you to be able to tell it.”

“You think I’m an alcoholic or something?”

“I think you’re a bundle of nerves. Pour alcohol on a bundle of nerves and it generally turns into a can of worms. While I’m making suggestions you might as well get rid of those chips you’re wearing on both shoulders. Somebody’s liable to knock them off and take a piece of you with them.”

He sat for a while with his head down. His face had an almost fluorescent pallor, and a faint humming tremor went through him.

“I’m not my usual self, I admit that. I didn’t know things like this could happen to people.”

“It’s about time you told me what did happen. Why not start at the beginning?”

“You mean when she left the hotel?”

“All right. Start with the hotel.”

“We were staying at the Surf House,” he said, “right here in Pacific Point. I couldn’t really afford it but Dolly wanted the experience of staying there – she never had. I figured a threeday weekend wouldn’t break me. It was the Labor Day weekend. I’d already used my vacation time, and we got married that Saturday so that we could have at least a three-day honeymoon.”

“Where were you married?”

“In Long Beach, by a judge.”

“It sounds like one of these spur-of-the-moment weddings.”

“I suppose it was, in a way. We hadn’t known each other too long. Dolly was the one, really, who wanted to get married right now. Don’t think I wasn’t eager. I was. But my parents thought we should wait a bit, until we could find a house and have it furnished and so on. They would have liked a church wedding. But Dolly wanted to be married by a judge.”

“What about her parents?”

“They’re dead. She has no living relatives.” He turned his head slowly and met my eyes. “Or so she claims.”

“You seem to have your doubts about it.”

“Not really. It’s just that she got so upset when I asked her about her parents. I naturally wanted to meet them, but she treated my request as though I was prying. Finally she told me her entire family was dead, wiped out in an auto accident.”

“Where?”

“I don’t know where. When it comes right down to it, I don’t know too much about my wife. Except that she’s a wonderful girl,” he added in a rush of loyal feeling slightly flavored with whisky. “She’s beautiful and intelligent and good and I know she loves me.” He was almost chanting, as though by wishful thinking or sheer incantation he could bend reality back into shape around him.

Читать дальше