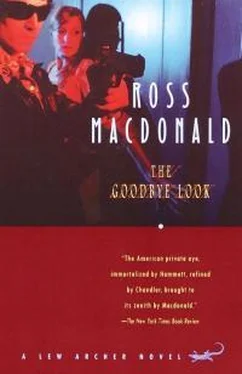

Ross Macdonald

THE GOODBYE LOOK

1969

The lawyer, whose name was John Truttwell, kept me waiting in the outer room of his offices. It gave the room a chance to work me over gently. The armchair I was sitting in was covered in soft green leather. Oil paintings of the region, landscapes and seascapes, hung on the walls around me like subtle advertisements.

The young pink-haired receptionist turned from the switchboard. The heavy dark lines accenting her eyes made her look like a prisoner peering out through bars.

“I’m sorry Mr. Truttwell’s running so late. It’s that daughter of his,” the girl said rather obscurely. “He should let her go ahead and make her own mistakes. The way I have.”

“Oh?”

“I’m really a model. I’m just filling in at this job because my second husband ran out on me. Are you really a detective?”

I said I was.

“My husband is a photographer. I’d give a good deal to know who – where he’s living.”

“Forget it. It wouldn’t be worth it.”

“You could be right. He’s a lousy photographer. Some very good judges told me that his pictures never did me justice.”

It was mercy she needed, I thought.

A tall man in his late fifties appeared in the open doorway. High-shouldered and elegantly dressed, he was handsome and seemed to know it. His thick white hair was carefully arranged on his head, as carefully arranged as his expression.

“Mr. Archer? I’m John Truttwell.” He shook my hand with restrained enthusiasm and moved me along the corridor to his office. “I have to thank you for coming down from Los Angeles so promptly, and I apologize for keeping you waiting. Here I’m supposed to be semi-retired but I’ve never had so many things on my mind.”

Truttwell wasn’t as disorganized as he sounded. Through the flow of language his rather sad cold eyes were looking me over carefully. He ushered me into his office and placed me in a brown-leather chair facing him across his desk.

A little sunlight filtered through the heavily draped windows, but the room was lit by artificial light. In its diffused whiteness Truttwell himself looked rather artificial, like a carefully made wax image wired for sound. On a wall shelf above his right shoulder was a framed picture of a clear-eyed blonde girl who I supposed was his daughter.

“On the phone you mentioned a Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence Chalmers.”

“So I did.”

“What’s their problem?”

“I’ll get to that in a minute or two,” Truttwell said. “I want to make it clear at the beginning that Larry and Irene Chalmers are friends of mine. We live across from each other on Pacific Street. I’ve known Larry all my life, and so did our parents before us. I learned a good deal of my law from Larry’s father, the judge. And my late wife was very close to Larry’s mother.”

Truttwell seemed proud of the connection in a slightly unreal way. His left hand drifted softly over his side hair, as if he was fingering an heirloom. His eyes and voice were faintly drowsy with the past.

“The point I’m making,” he said, “is that the Chalmerses are valuable people – personally valuable to me. I want you to handle them with great care.”

The atmosphere of the office was teeming with social pressures. I tried to dispel one or two of them. “Like antiques?”

“Somewhat, but they’re not old. I think of the two of them as objects of art, the point of which is that they don’t have to be useful.” Truttwell paused, and then went on as if struck by a new thought. “The fact is Larry hasn’t accomplished much since the war. Of course he’s made a great deal of money, but even that was handed to him on a silver platter. His mother left him a substantial nest egg, and the bull market blew it up into millions.”

There was an undertone of envy in Truttwell’s voice, suggesting that his feelings about the Chalmers couple were complicated and not entirely worshipful. I let myself react to the nagging undertone:

“Am I supposed to be impressed?”

Truttwell gave me a startled look, as if I’d made an obscene noise, or allowed myself to hear one. “I can see I haven’t succeeded in making my point. Larry Chalmers’s grandfather fought in the Civil War, then came to California and married a Spanish land-grant heiress. Larry was a war hero himself, but he doesn’t talk about it. In our instant society that makes him the closest thing we have to an aristocrat.” He listened to the sound of the sentence as though he had used it before.

“What about Mrs. Chalmers?”

“Nobody would describe Irene as an aristocrat. But,” he added with unexpected zest, “she’s a hell of a good-looking woman. Which is all a woman really has to be.”

“You still haven’t mentioned what their problem is.”

“That’s partly because it’s not entirely clear to me.” Truttwell picked up a sheet of yellow foolscap from his desk and frowned over the scrawlings on it. “I’m hoping they’ll speak more freely to a stranger. As Irene laid out the situation to me, they had a burglary at their house while they were away on a long weekend in Palm Springs. It was a rather peculiar burglary. According to her, only one thing of value was taken – an old gold box that was kept in the study safe. I’ve seen that safe – Judge Chalmers had it put in back in the twenties – and it would be hard to crack.”

“Have Mr. and Mrs. Chalmers notified the police?”

“No, and they don’t plan to.”

“Do they have servants?”

“They have a Spanish houseman who lives out. But they’ve had the same man for over twenty years. Besides, he drove them to Palm Springs.” He paused, and shook his white head. “Still it does have the feel of an inside job, doesn’t it?”

“Do you suspect the servant, Mr. Truttwell?”

“I’d rather not tell you whom or what I suspect. You’ll work better without too many preconceptions. Well as I know Irene and Larry, they’re very private people, and I don’t pretend to understand their lives.”

“Have they any children?”

“One son, Nicholas,” he said in a neutral tone.

“How old is he?”

“Twenty-three or four. He’s due to graduate from the university this month.”

“In January?”

“That’s right. Nick missed a semester in his freshman year. He left school without telling anyone, and dropped out of sight completely for several months.”

“Are his parents having trouble with him now?”

“I wouldn’t put it that strongly.”

“Could he have done this burglary?”

Truttwell was slow in replying. Judging by the changes in his eyes, he was trying out various answers mentally: they ranged from prosecution to defense.

“Nick could have done it,” he said finally. “But he’d have no reason to steal a gold box from his mother.”

“I can think of several possible reasons. Is he interested in women?”

Truttwell said rather stiffly: “Yes, he is. He happens to be engaged to my daughter Betty.”

“Sorry.”

“Not at all. You could hardly be expected to know that. But do be careful what you say to the Chalmerses. They’re accustomed to leading a very quiet life, and I’m afraid this business has really upset them. The way they feel about their precious house, it’s as if a temple had been violated.”

He crumpled the yellow foolscap in his hands and threw it into a wastebasket. The impatient gesture gave the impression that he would be glad to be rid of Mr. and Mrs. Chalmers and their problems, including their son.

Pacific Street rose like a slope in purgatory from the poor lower town to a hilltop section of fine old homes. The Chalmerses’ California Spanish mansion must have been fifty or sixty years old, but its white walls were immaculate in the late-morning sun.

Читать дальше