“I haven’t finished.” For the first time she was impatient, carried along by her story. “It was Thursday noon when I met them in the restaurant. I saw the old convertible again on Friday night. It was parked in front of the Chalmerses’ house. We live diagonally across the street and I can see their house from the window of my workroom. Just to make sure that it was Mr. Harrow’s car, I went over there to check on the registration. This was about nine o’clock Friday night.

“It was his, all right. He must have heard me close the car door. He came rushing out of the Chalmerses’ house and asked me what I was doing there. I asked him what he was doing. Then he slapped my face and started to twist my arm. I must have let out some kind of a noise, because Nick came out of the house and knocked Mr. Harrow down. Mr. Harrow got a revolver out of his car and I thought for a minute he was going to shoot Nick. They had a funny look on both their faces, as if they were both going to die. As if they really wanted to kill each other and be killed.”

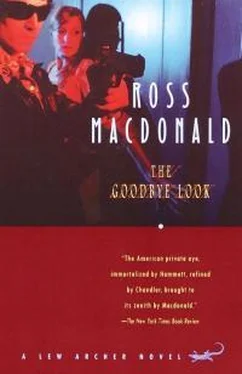

I knew that goodbye look. I had seen it in the war, and too many times since the war.

“But the woman,” the girl said, “came out of the house and stopped them. She told Mr. Harrow to get into his car. Then she got in and they drove away. Nick said that he was sorry, but he couldn’t talk to me right then. He went into the house and closed the door and locked it.”

“How do you know he locked it?”

“I tried to get in. His parents were away, in Palm Springs, and he was terribly upset. Don’t ask me why. I don’t understand it at all, except that that woman is after him.”

“Do you know that?”

“She’s that kind of woman. She’s a phony blonde with a big red sloppy mouth and poisonous eyes. I can’t understand why he would flip over her.”

“What makes you think he has?”

“The way she talked to him, as if she owned him.”

“Have you told your father about this woman?”

She shook her head. “He knows I’m having trouble with Nick. But I can’t tell him what it is. It makes Nick look so bad.”

“And you want to marry Nick.”

“I’ve waited for a long time.” She turned and faced me. I could feel the pressure of her cool insistence, like water against a dam. “I intend to marry him, whether my father wants me to or not. I’d naturally prefer to have his approval.”

“But he’s opposed to Nick?”

Her face thinned. “He’d be opposed to any man whom I wanted to marry. My mother was killed in 1945. She was younger then than I am now,” she added in faint surprise. “Father never remarried, for my sake. I wish for my sake he had.”

She spoke with the measured emphasis of a young woman who had suffered. “How old are you, Betty?”

“Twenty-five.”

“How long is it since you’ve seen Nick?”

“Not since Friday night, at his house.”

“And you’ve been waiting for him here since then?”

“Part of the time. Dad would worry himself sick if I didn’t come home at night. Incidentally, Nick hasn’t slept in his own bed since I started waiting for him here.”

“When was that?”

“Saturday afternoon.” She added with a seasick look: “If he wants to sleep with her, let him.”

At this point the telephone rang. She rose quickly and answered it. After listening for a moment she spoke rather grimly into the receiver:

“This is Mr. Chalmers’ answering service … No, I don’t know where he is … Mr. Chalmers does not provide me with that information.”

She listened again. From where I sat I could hear a woman’s emotional voice on the line, but I couldn’t make out her words. Betty repeated them: “ ‘Mr. Chalmers is to stay away from the Montevista Inn.’ I see. Your husband has followed you there. Shall I tell him that? … All right.”

She put the receiver down, very gently, as if it was packed with high explosives. The blood mounted from her neck and suffused her face in a flush of pure emotion.

“That was Mrs. Trask.”

“I was wondering. I gather she’s at the Montevista Inn.”

“Yes. So is her husband.”

“I may pay them a visit.”

She rose abruptly. “I’m going home. I’m not going to wait here any longer. It’s humiliating.”

We went down together in the elevator. In its automatic intimacy she said:

“I’ve spilled all my secrets. How do you make people do it?”

“I don’t. People like to talk about what’s hurting them. It takes the edge off the pain sometimes.”

“May I ask you one more painful question?”

“This seems to be the day for them.”

“How was your mother killed?”

“By a car, right in front of our house on Pacific Street.”

“Who was driving?”

“Nobody knows, least of all me. I was just a small baby.”

“Hit-run?”

She nodded. The doors slid open at the ground floor, terminating our intimacy. We went out together to the parking lot. I watched her drive off in a red two-seater, burning rubber as she turned into the street.

Montevista lay on the sea just south of Pacific Point. It was a rustic residential community for woodland types who could afford to live anywhere.

I left the freeway and drove up an oak-grown hill to the Montevista Inn. From its parking lot the rooftops below seemed to be floating in a flood of greenery. I asked the young man in the office for Mrs. Trask. He directed me to Cottage Seven, on the far side of the pool.

A bronze dolphin spouted water at one end of the big old-fashioned pool. Beyond it a flagstone path meandered through live oaks toward a white stucco cottage. A red-shafted flicker took off from one of the trees and crossed a span of sky, wings opening and closing like a fan lined with vivid red.

It was a nice place to be, except for the sound of the voices from the cottage. The woman’s voice was mocking. The man’s was sad and monotonous. He was saying:

“It isn’t so funny, Jean. You can wreck your life just so many times. And my life, it’s my life, too. Finally you reach a point where you can’t put it back together. You should learn a lesson from what happened to your father.”

“Leave my father out of this.”

“How can I? I called your mother in Pasadena last night, and she says you’re still looking for him. It’s a wild-goose chase, Jean. He’s probably been dead for years.”

“No! Daddy’s alive. And this time I’m going to find him.”

“So he can ditch you again?”

“He never ditched me.”

“That’s the way I heard it from your mother. He ditched you both and took off with a piece of skirt.”

“He did not.” Her voice was rising. “You mustn’t say such things about my father.”

“I can say them if they’re true.”

“I won’t listen!” she cried. “Get out of here. Leave me alone.”

“I will not. You’re coming home to San Diego with me and put up a decent front. You owe me that much after twenty years.”

The woman was silent for a moment. The sounds of the place lapped in like gentle waves: a towhee foraging in the underbrush, a kinglet rattling. Her voice, when she spoke again, was calmer and more serious:

“I’m sorry, George, I truly am, but you might as well give up. I’ve heard everything you’re saying so often, it just goes by like wind.”

“You always came back before,” he said with a note of hopefulness in his voice.

“This time I’m not.”

“You have to, Jean.”

His voice had thinned. Its hopefulness had twisted into a kind of threat. I began to move around the side of the cottage.

“Don’t you dare touch me,” she said.

“I have a legal right to. You’re my wife.”

Читать дальше