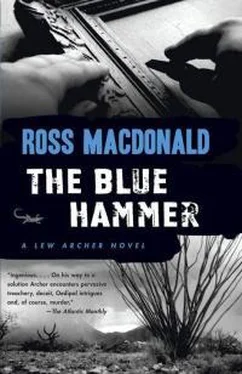

Ross Macdonald

THE BLUE HAMMER

1976

To William Campbell Gault

I drove up to the house on a private road that widened at the summit into a parking apron. When I got out of my car I could look back over the city and see the towers of the mission and the courthouse half submerged in smog. The channel lay on the other side of the ridge, partly enclosed by its broken girdle of islands.

The only sound I could hear, apart from the hum of the freeway that I had just left, was the noise of a tennis ball being hit back and forth. The court was at the side of the house, enclosed by high wire mesh. A thick-bodied man in shorts and a linen hat was playing against an agile blond woman. Something about the trapped intensity of their game reminded me of prisoners in an exercise yard.

The man lost several points in a row and decided to notice my presence. Turning his back on the woman and the game, he came toward the fence.

“Are you Lew Archer?”

I said I was.

“You’re late for our appointment.”

“I had some trouble finding your road.”

“You could have asked anybody in town. Everybody knows where Jack Biemeyer lives. Even the planes coming in use my home as a landmark.”

I could see why. The house was a sprawling pile of white stucco and red tile, set on the highest point in Santa Teresa. The only things higher were the mountains standing behind the city and a red-tailed hawk circling in the bright October sky.

The woman came up behind Biemeyer. She looked much younger than he did. Both her narrow blond head and her pared-down middle-aged body seemed to be hyperconscious of my eyes. Biemeyer didn’t introduce us. I told her who I was.

“I’m Ruth Biemeyer. You must be thirsty, Mr. Archer. I know I am.”

“We won’t go into the hospitality routine,” Biemeyer said. “This man is here on business.”

“I know that. It was my picture that was stolen.”

“I’ll do the talking, Ruth, if you don’t mind.”

He took me into the house, his wife following us at a little distance. The air was pleasantly cool inside, though I could feel the weight of the structure surrounding and hanging over me. It was more like a public building than a house – the kind of place where you go to pay your taxes or get a divorce.

We trekked to the far side of a big central room. Biemeyer pointed at a white wall, empty except for a pair of hooks on which he said the picture had been hung.

I got out my notebook and ball-point pen. “When was it taken?”

“Yesterday.”

“That was when I first noticed that it was missing,” the woman said. “But I don’t come into this room every day.”

“Is the picture insured?”

“Not specifically,” Biemeyer said. “Of course everything in the house is covered by some insurance.”

“Just how valuable is the picture?”

“It’s worth a couple of thousand, maybe.”

“It’s worth a lot more than that,” the woman said. “Five or six times that, anyway. Chantry’s prices have been appreciating.”

“I didn’t know you’d been keeping track of them,” Biemeyer said in a suspicious tone. “Ten or twelve thousand? Is that what you paid for that picture?”

“I’m not telling you what I paid for it. I bought it with my own money.”

“Did you have to do it without consulting me? I thought you’d gotten over being hipped on the subject of Chantry.”

She became very still. “That’s an uncalled-for remark. I haven’t seen Richard Chantry in thirty years. He had nothing to do with my purchase of the picture.”

“I hear you saying so, anyway.”

Ruth Biemeyer gave her husband a quick bright look, as if she had taken a point from him in a harder game than tennis. “You’re jealous of a dead man.”

He let out a mirthless laugh. “That’s ridiculous on two counts. I know bloody well I’m not jealous, and I don’t believe he’s dead.”

The Biemeyers were talking as though they had forgotten me, but I suspected they hadn’t. I was an unwilling referee who let them speak out on their old trouble without the danger that it would lead to something more immediate, like violence. In spite of his age Biemeyer looked and talked like a violent man, and I was getting tired of my passive role.

“Who is Richard Chantry?”

The woman looked at me in surprise. “You mean you’ve never heard of him?”

“Most of the world’s population have never heard of him,” Biemeyer said.

“That simply isn’t true. He was already famous before he disappeared, and he wasn’t even out of his twenties.”

Her tone was nostalgic and affectionate. I looked at her husband’s face. It was red with anger, and his eyes were confused. I edged between them, facing his wife.

“Where did Richard Chantry disappear from?”

“From here,” she said. “From Santa Teresa.”

“Recently?”

“No. It was over twenty-five years ago. He simply decided to walk away from it all. He was in search of new horizons, as he said in his farewell statement.”

“Did he make the statement to you, Mrs. Biemeyer?”

“Not to me, no. He left a letter that his wife made public. I never saw Richard Chantry again after our early days in Arizona.”

“It’s not for want of trying,” her husband said. “You wanted me to retire here because this was Chantry’s town. You got me to build a house right next to his house.”

“That isn’t true, Jack. It was your idea to build here. I simply went along with it, and you know it.”

His face lost its flush and became suddenly pale. There was a stricken look in his eyes, as he realized that his mind had slipped a notch.

“I don’t know anything any more,” he said in an old man’s voice, and left the room.

His wife started after him and then turned back, pausing beside a window. Her face was hard with thought.

“My husband is a terribly jealous man.”

“Is that why he sent for me?”

“He sent for you because I asked him to. I want my picture back. It’s the only thing I have of Richard Chantry’s.”

I sat on the arm of a deep chair and reopened my notebook. “Describe it for me, will you?”

“It’s a portrait of a youngish woman, rather conventionalized. The colors are simple and bright, Indian colors. She has yellow hair, a red and black serape. Richard was very much influenced by Indian art in his early period.”

“Was this an early painting?”

“I don’t really know. The man I bought it from couldn’t date it.”

“How do you know it’s genuine?”

“I think I can tell by looking at it. And the dealer vouched for its authenticity. He was close to Richard back in the Arizona days. He only recently came here to Santa Teresa. His name is Paul Grimes.”

“Do you have a photograph of the painting?”

“I haven’t, but Mr. Grimes has. I’m sure he’d let you have a look at it. He has a small gallery in the lower town.”

“I better talk to him first. May I use your phone?”

She led me into a room where her husband was sitting at an old rolltop desk. The scarred oak sides of the desk contrasted with the fine teakwood paneling that lined the walls. Biemeyer didn’t look around. He was studying an aerial photograph that hung above the desk. It was a picture of the biggest hole in the ground I’d ever seen.

He said with nostalgic pride, “That was my copper mine.”

“I’ve always hated that picture,” his wife said. “I wish you’d take it down.”

“It bought you this house, Ruth.”

“Lucky me. Do you mind if Mr. Archer uses the phone?”

“Yes. I do mind. There ought to be some place in a four-hundred-thousand-dollar building where a man can sit down in peace.”

Читать дальше