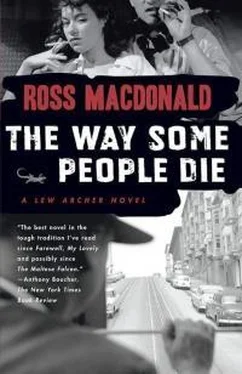

Росс Макдональд - The Way Some People Die

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Росс Макдональд - The Way Some People Die» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Way Some People Die

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Way Some People Die: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Way Some People Die»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The third Lew Archer mystery, in which a missing-persons search takes him "through slum alleys to the luxury of a Palm Springs resort, to a San Francisco drug-peddler's shabby room. Some of the people were dead when he reached them. Some were broken. Some were vicious babes lost in an urban wilderness.

The Way Some People Die — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Way Some People Die», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She stirred sleepily at her end of the bed. “You’ve been dead to the world for two hours. It isn’t very flattering. Besides, you snore.”

“Sorry. I missed my sleep last night.”

“I didn’t mind, really. You sounded like my father. My father was quite a guy. He died when I was eight.”

“And you remember what his snoring sounded like?”

“I have an excellent memory.” She stretched and yawned. “Do you suppose they’ll ever let us out of here?”

“Your guess is as good as mine.” I threw aside the spread and stood up. “Nice of you to tuck me in.”

“Professional training. Which reminds me, now that Joe is gone, I suppose I’ll have to get myself a job. He didn’t leave me anything but my clothes.”

I remembered the condition of the clothes in the Casa Loma apartment, and kept quiet on the subject. “You’re giving him up pretty easily, aren’t you?”

“He won’t be back,” she said flatly. “If he does come back, he won’t survive. And even if he did, I wouldn’t take him back. Not after what he said to me last night.”

I looked my question.

“We won’t go into it,” she said.

She flung herself off the bed and walked to the other end of the room, soft-footed in her stockings. Her narrow high-heeled shoes stood together neatly on the floor. She leaned toward the dressing-table mirror, lifting her hair to examine the bruise on her temple.

“God damn it, I can’t stand waiting. I think I’ll smash something.” She swung around fiercely.

“Go ahead.”

There was a perfume atomizer on the table. She picked it up and hurled it at the door. The perfume splattered, and bits of glass rained down.

“You’ve made the place smell like a hothouse.”

“I feel better, anyway. Why don’t you break something?”

“It takes a skull to satisfy me. Is Joe long-headed or round-headed? Better put on your shoes or you’ll cut your feet.”

“Round-headed, I guess.” Standing first on one leg and then on the other, she slipped the narrow shoes on. Her legs were beautiful.

“I like the round-headed ones especially. They’re like cracking walnuts, one of the happiest memories from my childhood.”

She stood and faced me with her hands on her hips. “You talk a good fight, Archer. Joe can be rough, you know that.”

“Tell me more.”

But there were hustling footsteps in the corridor. The key turned in the lock. It was Dowser himself, in beige slacks and a chocolate jacket.

He jerked his thumb at me. “Out. I want to talk to you.”

“What about me?” the girl said.

“Calm down. You can go home as far as I’m concerned. Only don’t try to skip out, I want you around.” He turned to Blaney behind him. “Take her home.”

Blaney looked disappointed. She called out “Good luck, Archer” as he marched her away.

I followed Dowser into the big room with the bar. The curly-headed Irishman was shooting practice shots on the snooker table. He straightened up as the boss came in, presenting arms with his cue.

“I got a job for you, Sullivan,” Dowser said. “You’re going to Ensenada and see Torres. I talked to him on the telephone, so he knows you’re coming. You stick with Torres until Joe shows up.”

“Is Joe in Ensenada?”

“There’s a chance he’ll turn up there. The Aztec Queen is gone, and it looks as if he took it. You can have the Lincoln, and make it fast, huh?”

Sullivan started out and paused, fingering his black bow-tie: “What do I do with Joe?”

“Give him my best regards. You take orders from Torres.”

Dowser turned to me the big executive with more responsibility on his shoulders than one man should rightly have to bear. But always a genial host: “Want a drink?”

“Not on an empty stomach.”

“Something to eat?”

“Most jails provide board for the prisoners.”

He gave me a hurt look, and beat on the floor with the butt of the abandoned cue. “You’re not my prisoner, baby, you’re my guest. You can leave whenever you want.”

“How about now?”

“Don’t be in such a hurry.” He hammered the floor still harder, and raised his voice: “Where the hell is everybody around here? I pay them double wages so they leave me stranded in the middle of the day, Hey! Fenton!”

“You should have a bell to ring.”

An old man answered the summons at a limping run. “I was lying down, Mr. Dowser. You want something?” His eyes were bleared with sleep.

“Get Archer here something to eat. A couple of ham sandwiches and some buttermilk for me. Hurry.”

The old man ran out of the room, his shirtsleeved elbows flapping, the long white hair on his head ruffled by his own wind.

“He’s the butler,” Dowser said with satisfaction. “He’s English, he used to work for a producer in Bel-Air. I should of made him talk for you, you ought to hear him talk. I’ll make him talk when he comes back, huh? Ten-dollar words!”

“I’m afraid I have to leave,” I said.

“Stick around, baby. I might have plenty of use for a man like you. That was the straight dope you got from the girl. I went to the Point and checked it personally. The bastard lammed in his brother’s boat all right.”

“Did you have to keep me locked up until you checked?”

“Come on, boy, I was doing you a favor. Don’t tell me you didn’t make out?” He leaned over the green table and sank a long shot in one of the far pockets. “How about a game of snooker, huh? A dollar a point, and I’ll spot you twenty. You’ll make money off me.”

I was getting restless. The friendlier Dowser grew, the less I liked him. On the other hand, I didn’t want to offend him. An idea for taking care of Dowser was forming at the back of my head, where it hurt, and I wanted to be able to come back to his house. I said that he was probably a shark and that I hadn’t played the game for years. But I took a cue from the rack at the end of the bar.

I hardly got a chance to use my cue. Dowser made a series of brilliant runs, and took me for thirty dollars in ten minutes.

“You know,” he said reminiscently, chalking his cue, “I made my living at this game for three years when I was a kid. I was going to be another Willie Hoppe. Then I found out I could fight: there’s quicker money in fighting. I come up the hard way.” He touched his rosebud ear with chalk-greened fingers. “How about another?”

“No, thanks. I’ll have to be shoving off.”

But then the butler came back with the sandwiches. He was wearing a black coat now, and had brushed his hair. “Do you wish to eat at the bar, sir?”

“Yeah. Fenton, say a ten-dollar word for Archer here.”

The old man answered him with a straight face: “Antidisestablishment-arianism. Will that do, sir? It was one of Mr. Gladstone’s coinages, I believe.”

“How about that?” Dowser said to me. “This Gladstone was one of those English big shots, a lord or something.”

“He was Prime Minister, sir.”

“Prime Minister, that’s it. You can go now, Fenton.”

Dowser insisted that I share the buttermilk, on the grounds that it was good for the digestion. We sat side by side at the bar and drank it from chilled metal mugs. He became vivacious over his. He could tell that I was an honest man, and he liked me for it. He wanted to do things for me. Before he finished, he had offered me a job at four hundred dollars a week, and showed me the money-clip twice. I told him I liked working for myself.

“You can’t make twenty thousand a year working for yourself.”

“I do all right. Besides, I have a future.”

I had touched a sore spot. “What do you mean by that?” His eyes seemed to swell like leeches sucking blood from his face.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Way Some People Die»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Way Some People Die» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Way Some People Die» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.