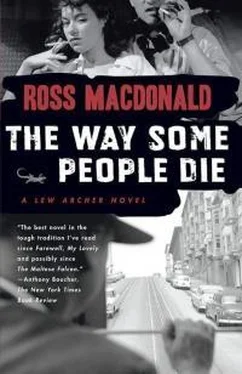

Росс Макдональд - The Way Some People Die

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Росс Макдональд - The Way Some People Die» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Way Some People Die

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Way Some People Die: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Way Some People Die»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The third Lew Archer mystery, in which a missing-persons search takes him "through slum alleys to the luxury of a Palm Springs resort, to a San Francisco drug-peddler's shabby room. Some of the people were dead when he reached them. Some were broken. Some were vicious babes lost in an urban wilderness.

The Way Some People Die — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Way Some People Die», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He laughed his unenjoyable laugh. “You’d like to know, huh?”

“When I get beaten over the head, I’m interested in the reason.”

“I’ll tell you the reason. Tarantine has something of mine, you maybe guessed it, huh? I’m going to get it back. The girl says she don’t know nothing about it.”

“What does it look like?”

“That doesn’t matter. He won’t be toting it around with him. When I get him, then I get it afterwards.”

“Junk,” I said under my breath. If he heard me he paid no attention.

“You working for me, Archer?”

“Not for love.”

“I offered you five grand for Tarantine. I’ll raise it five.”

“You offered me one for Galley. You’re full of offers.” I was watching his face closely, to see how far I could go in that direction.

“Be reasonable,” he said. “You brought her in, I’d of slipped you the cash just like an expressman at the door. You didn’t bring her. Blaney had to go and get her himself. I can’t afford to throw money away on good will. My expenses are a friggin’ crime these days. I got a payroll that would break your heart and now the lawyers tell me I got to pay back income-tax to clear myself with the feds.” His voice was throbbing with the injustice of it all. “Not to mention the politicians,” he added. “The Goddamn politicians bleed me white.”

“Five hundred, then,” I said. “We’ll split the difference.”

“Five hundred dollars for nothing?” But he was just haggling now, trying to convert a bargain to a steal.

“Last night it was a thousand. Only last night you didn’t have the girl.”

“The girl is no good to me. If she knows where Joe Tarantine is, she isn’t telling.”

“Let me talk to her?” Which was the point I had been aiming at from the beginning.

“She’ll talk for me. It takes a little time.” He stood up, tightening the sash around his flabby waist. There was something womanish about the gesture, though the muscles bulged like angry veins in his sleeves.

On his feet he looked smaller. His legs were proportionately shorter than his body. I stayed in my chair. Dowser would be more likely to do what I wanted him to do if he could look down at the top of my head. There were two-inch heels on the sandals that clasped his feet.

“A little time,” I repeated. “Isn’t that what Tarantine needs to get lost in Mexico? Or wherever he’s gone.”

“I can extradite him,” he said with his canine grin. “All I need to know is where he is.”

“And if she doesn’t know?”

“She knows. She’ll remember. A man don’t leave behind a piece like her. Not Joey. He loves his flesh.”

“Speaking of flesh, what have you been doing to the girl?”

“Nothing much.” He shrugged his heavy shoulders. “Blaney pushed her around a little bit. I guess now I got my strength up I’ll push her around a little bit myself.” He punched himself in the abdomen, not very hard.

“I wish you’d let me talk to her,” I said.

“Why all the eager interest, baby?”

“Tarantine sapped me.”

“He didn’t sap you in the moneybags, baby. That’s where you get the real agony.”

“No doubt. But here’s my idea. The girl has a notion I might be on her side.” If Galley had that notion, she was right. “If you muss my hair and shove me in alongside her, it should convince her. I suppose you’ve got her locked in some dungeon?”

“You want to stool for me, is that the pitch?”

“Call it that. When do I get my five hundred?”

He dug deep into the pocket of his robe, slipped a bill from the gold money-clip and tossed it on the table. “There’s your money.”

I rose and picked it up against my will, telling myself it was justified under the circumstances. Taking his money was the only way I knew to make Dowser trust me. I folded the bill and tucked it into the watch pocket, separate from the other money, promising myself that at the earliest opportunity I’d bet it on the horses.

“It might be a good idea,” he said. “You have a talk with the girl before we rough her up too much. I kind of like her looks the way she is. Maybe you do too, huh?” The bulging eyes shone with a lewd cunning.

“She’s a lovely piece,” I said.

“Well, don’t start getting any ideas. I’ll put you in where she is, see, and all you do is talk to her. Along the lines we discussed. I got a mike in there, and a one-way window. I put the one-way window in for the politicians. They come to visit me sometimes, see. I take my own sex straight.”

So does a coyote, I thought, and did not say.

Chapter 15

After the sunswept patio, the room was very dim behind three-quarters-drawn drapes. A thin partition of light fell through it from the uncovered strip of window, dividing it into two unequal sections. The section to my right held a dressing-table and a long chair upholstered in dark red satin. I saw myself in the mirror above the dressing-table. I looked disheveled enough without even trying. The heavy door slammed shut and a key turned in the lock.

In the section to my left there were more chairs, a wide bed with a red silk padded head, a portable cellarette beside the bed in lieu of a bedside table. Galley Tarantine crouched on the bed like a living piece of the dimness and the stillness. Only the amber discs of her eyes showed life. Then the point of her tongue made a slow circuit of her lips at the pace of a second hand: “This is an unexpected pleasure. I didn’t know I was going to have a cellmate. The right sex, too.” There was some irony there. Her voice, low and intense, was well adapted to it.

“You’re very observant.” I went to the window and found that it was a casement, but bolted top and bottom on the outside.

“It isn’t much use,” she said. “Even if you smashed it, the place is too well guarded to get away from. Dowser plays with gunmen the way other spoiled little boys play with lead soldiers. He thinks he’s Napoleon Bonaparte and he probably suffers from the same anatomical deficiency. I wouldn’t know myself. I wouldn’t let him touch me with a ten-foot pole.” She spoke quietly but clearly, apparently taking pleasure in the sound of her own voice, though it had growling overtones. I hoped that Dowser was hearing all of this, and wondered where the mike was. Perhaps in the cellarette. I turned from the window to look at it, and the light fell on my face. The woman sat up higher on her heels and let out a little gasp of recognition. “You’re Archer! How did you get here?”

“It all goes back about thirty-seven years ago.” She was too bright for a Lochinvar approach. “A few months before I was born, my mother was frightened by a tall dark stranger with a sandbag. It had a queer effect on my infant brain. Whenever anybody hits me with a sandbag, I fall down and get up angry.”

“You touch me deeply,” she said. “How did you know it was a sandbag?”

“I’ve been sandbagged before.” I sat down on the foot of the bed and fingered the back of my head. The swelling there was as sore as a boil.

“I’m sorry. I tried to stop it, but Joe was too fast. He sneaked out the back of the house and around the porch in his stocking feet. You’re lucky he didn’t shoot you.” She shuffled towards me on her knees, her hips rotating with a clumsy kind of grace. “Let me look at it.”

I bent my head. Her fingers moved cool and gentle on the swelling. “It doesn’t look too bad. I don’t think there’s any concussion, not much anyway.” Her fingers slid down the nape of my neck.

I looked up into the narrow face poised over me. The full red lips were parted and the black eyes dreamed downward heavily. Her hair was uncombed. She had sleepless hollows under her eyes, a dark bruise on her temple. She still was the fieriest thing I’d seen up close for years.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Way Some People Die»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Way Some People Die» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Way Some People Die» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.