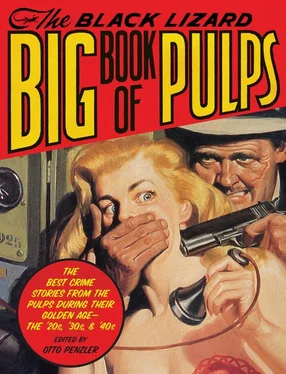

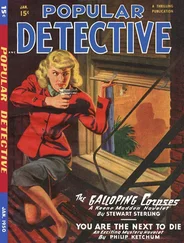

When girls (and they were usually called girls, or dolls, or, heaven help us, frails, or some term of endearment like honey or sugar or baby or cutie) took the role of detective, they tended to be acceptable to male readers mainly when they were assistants, girlfriends, or professional sidekicks, such as reporters. Their roles were predictable in most stories. If they weren’t present as comic relief, they needed to be rescued. It would be impossible to calculate the number of pretty young things who were kidnapped or held hostage until our hero burst through a door on the last page to save her — often from a fate worse than death. One needs only to look at the colorful cover paintings that adorned the magazines for evidence of this cliché. It is a rare cover indeed that does not display a buxom beauty in a low-cut dress or sweater, frequently in tatters, being menaced by a thug or gang of thugs.

Some of the lesser pulps, those that paid even less than the standard penny a word, began to feature women in the second decade of the detective pulps, the 1930s, while those that sought an audience with racier material, such as Gun Molls, Saucy Stories, and Spicy Detective, had even more ample reason to feature them. In these pages, opportunities for placing luscious young beauties in grave peril of violation were rampant, providing titillation to young male readers who hid their ten-cent purchases inside newspapers or more respectable journals.

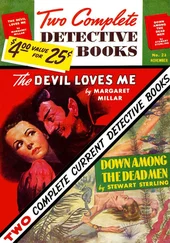

One role in crime fiction in which women have been featured with some regularity is as the criminals. The pages of the pulps are rich with female jewel thieves of a certain elegance who seem always to be in formal attire at a country house party or a penthouse soiree. They function largely in the same manner as their male counterparts, though they are often required to use their seductive beauty to escape capture. Tough broads appeared in later pulps, either as out-and-out hoodlums or, more frequently but no less dangerously, as gun molls for their gangster boyfriends.

All types of female detectives and crooks who first saw the light of day in pulp magazines appear in section three of this book. There are independent private investigators, assistants, rogues, victims, molls, police officers, and innocent bystanders. They are young and old, good looking and plain, funny and dour, brave and timid, violent and gentle, honest and crooked. In short, very much like their male counterparts.

While there is more than one way to judge the success of a pulp magazine, including longevity, circulation, and profitability, the undisputed champion in the area of having developed the greatest writers and having had the most long-lasting literary influence was Black Mask, and most of the stories in this collection were originally published in its pages. Had it done no more than publish Carroll John Daly’s first story, Black Mask would have achieved immortality. On May 15, 1923, with the publication of “Three Gun Terry,” the hard-boiled private eye made his first appearance, quickly followed by Daly’s creation of Race Williams, the first series character in hard-boiled fiction.

While Daly was truly a hack writer devoid of literary pretension, aspiration, and ability, he laid the foundation for the form that continues to flourish to this day in the work of such writers as Robert B. Parker, Joe Gores, James Crumley, Bill Pronzini, Michael Connelly, and James Lee Burke (although the latter two employ series characters who are cops, they function in the same individualistic way that private investigators do, and frequently use the same smart-aleck speech patterns as their kindred freelancers do).

Dashiell Hammett produced his first Continental Op story for Black Mask later in the same year, and the future of the genre was secure, as the editors and the reading public quickly recognized that this was serious literature in the guise of popular fiction. Every significant writer of the pulp era worked for Black Mask, including Paul Cain, Horace McCoy, Frederick L. Nebel, Raoul Whitfield, Erle Stanley Gardner, Charles G. Booth, Roger Torrey, Norbert Davis, George Harmon Coxe, and, of course, the greatest of them all, Raymond Chandler.

It was the era between the two World Wars in which the pulps flourished, their garish covers enticing readers and their cheap prices providing mass entertainment through the years of the Great Depression. It has been widely stated that the advent of television tolled the death knell for the pulps, but it is not true. They were replaced by the creation and widespread popularity of paperback books, virtually unknown as a mass market commodity before World War II.

There is quotable prose in these pages, and characters that you will remember, and fascinating evocations of another time and place, but the writers mainly had the goal of entertaining readers when these stories were produced. No reasonable reader will ever complain that the stories are slow moving, that they lack action and conflict — in short, that they are dull. Many of the contributors to this book went on to successful writing careers in other arenas, including Hollywood, but here is the real stuff: stories written at breakneck speed and designed to be read the same way.

Introduction by Harlan Coben

Dear Reader:

Oh man, do I envy you.

Welcome to the world of pulp fiction. If you have been here before, well, skip this introduction and dive in. You already have some idea of the delights that await. For the rest of you, I will keep this brief.

I know some writers who claim that they have never read pulp fiction. I put them in two classes. The larger group I call, for a lack of a better term, liars. Of course they have read pulp fiction. They may not know it. They may, because of the various connotations derived from the word “pulp,” not want to admit it. But come on now.

Reading pulp fiction is a bit like, uh, something else. Ninety percent of the writers out there admit they do it. Ten percent lie about it.

The second group, the writers who really have never read pulp fiction (yes, I know this contradicts the last paragraph where I basically said one hundred percent read it, but go with me here) — these are writers the rest of us do not associate with. They have poor self-esteem. They had a troubled home life. They are not fun at parties.

Discovering pulp fiction now, right now, is a bit like finding a lost treasure. You are unearthing something that will entertain, enlighten, amuse, horrify, mangle, jangle, keep you riveted. Decades after they were written, these stories still manage to have an edge.

Edge. That might be the key for me. These stories still cut, still tear, still even shock a bit. These guys experimented. They wrote on the move. They wrote, like Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde, for money. They went places maybe they shouldn’t have and we love them for it.

I like edge. I like it a lot. I think you will too.

Otto Penzler has carefully selected the greatest of the great from the history of pulp fiction. Legendary writers you’ve already heard of, like Dashiell Hammett, Erle Stanley Gardner, Cornell Woolrich, and Raymond Chandler, are here. Legendary writers that you should have heard of, like Frederick L. Nebel, Paul Cain, Carroll John Daly, George Harmon Coxe, Charles Booth, Leslie White, William Rollins, Norbert Davis, Horace McCoy, and Thomas Walsh, are also where they should be — with the greats.

In short: you got the goods here.

Finally, you have a great tour guide for this treasure hunt. Otto Penzler knows more about pulp fiction than pretty much anyone else I know. He also has self-esteem, a fine home life, and man, is he fun at parties.

Okay, put a bullet in this. I’m done. Turn the page, dammit. Start reading.

Читать дальше