Dear Professor,

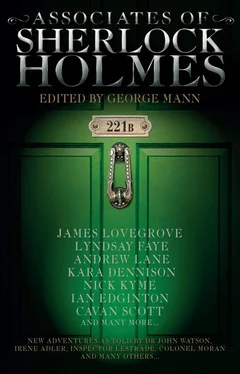

It is my honour and privilege to enclose within this parcel those curious and singular books that you requested in your last communication, namely:

(i) The Secret Life of a Ballerina

(ii) A Schoolgirl’s Education

(iii) Confessions of a Flagellant

(iv) Further Memoirs of a Courtesan

(v) A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus

I trust that these volumes shall educate and enchant in equal measure. Should you require further additions to your library, pray do not hesitate to renew our correspondence. Until that time, I would remind you respectfully of the ceaseless necessity of discretion and tact.

I remain, sir, your most humble servant,

E S Foote

Telegram

Sent: 3rd January 1913

From: Scheherazade

To: Panjandrum

Subject located. Extraction begun. Expect further word soon.

From the private journal of Professor C.R.H. Presbury

4th January 1913

More than a decade has passed since last I set pen to paper in this fashion. That was at a time before the delightful – if ultimately faithless – Miss Morphy came first within my purview, before the gentleman from Prague provided the chief instrument of my downfall, before the advent in my rich existence of that professional busybody Mr Sherlock Holmes and before the ignominious end of a career which cannot be characterised as having been anything other than amongst the very first rank. My life since those unhappy days, which saw the cessation of my engagement and the severing of all professional and personal ties of any significance, has been spent in quiet contemplation and solitary philosophical enquiry. I have been – let us not be circumspect – a long time indeed in the wilderness.

What, then, has occasioned my return to this journal, its pages, like the skin of its author, thin, worn and showing advanced signs of age? What has made me write once more of myself?

The answer is this: that an event has woken parts of my character that I had thought to have been forever buried, that the sight of a new face and the speaking of certain words has breathed again on embers in me and coaxed back into full flame the fires of an appetite which I have endeavoured in this long hermitage of mine to curb, to suppress and to cast aside.

It began this morning with a knock upon my study door. I was engaged in the perusal and study of certain antiquarian texts and, being cognisant of their fragility as well as their extreme rarity, I was careful to stow them away in the safest drawer of my desk before answering the bid for my attention with a sturdy “halloa!” It was, of course, Mrs Scott, my redoubtable, boot-faced housekeeper and maid of all work, the only representative of her sex nowadays with whom I pass any words of substance.

Her face was arranged so as to suggest an emotion of which I would not hitherto have thought her capable, namely a crude species of curiosity.

“Mrs Scott? What occasions this interruption?”

“You have a visitor, sir,” said she, her rustic origins evident in every elongated syllable. “A fine young woman.”

Even at these rare words I fancy that something shifted within me, that some new chain was forged.

“Did she give her name?”

In the manner of an angler presenting some oversized prize, Mrs Scott, with a decided flourish, produced a white business card. “See here.” And she passed the thing, with an odd admixture of wariness and pride, to me.

I looked down with considerable interest, callers of any kind being a rarity and those of this stranger’s sex and age unprecedented, and I saw written there four words.

The first, evidently the caller’s name, in bold type and gothic calligraphy, read:

Underneath, in more modern print, ran the legend:

TELLER OF TALES

“How very intriguing,” I said. “Now, really I think it is high time that you showed this singular young lady in, Mrs Scott. Don’t you?”

Given the consequences of so long and enforced a solitude, my imagination had, naturally enough, begun by this time to adopt the most fantastic postures. My breathing quickened and a raft of the most vivid and diverting imagery rose up before me. Those moments in which I was left alone in the study as Mrs Scott bustled in the hallways beyond were especially interminable.

Nonetheless (and how I find my hand a-trembling as I consign these thoughts to this secret depository) their sequel was to surpass even the most idealistic of my fancies. For, a minute or so later, the housekeeper returned and in her wake was a young woman of the rarest and most striking aspect, brunette, not more than five and twenty and in possession of a truly wonderful silhouette.

Her gaze met mine without the least sign of nervousness. She was dressed in a demure, even a somewhat antiquated fashion and her voice was gentle yet determined.

“Professor Presbury, I presume?”

I peeled back my lips. “I am most certainly he. To whatever do I owe this pleasure? Are we acquainted?”

That dear lady shook her noble head. There was something sweetly feline in the gesture. “I fear I have not until today had the pleasure of making your acquaintance in person. Although, of course, I feel that I know you through your work, so much of which I have read with the keenest interest.”

I waved away this compliment casually enough, although I admit that at the declaration I felt a distinct spasm of delight.

“Yet I do believe,” she murmured, something quietly imploring now in her big hazel eyes, “that you once knew my late father.”

“I may well have done,” I said. “Now what was that good man’s name?”

“Lowenstein,” she replied and showed me her sharp white teeth.

“Mrs Scott,” I said to that stout creature who had, throughout this conversation, lingered by the door. “Would you be so kind as to fetch Miss Lowenstein a pot of tea? Perhaps the walnut cake also? For this is somewhat in the spirit of a reunion, and we should mark it with all good things.”

The domestic nodded gruffly. Miss Lowenstein seemed delighted. “I do so love walnut cake.”

“Happy,” I said. “I am happy to oblige.”

“And yet?”

“Yes, Miss Lowenstein?”

“Today is not meant merely as a means by which we might revisit the past.”

“No?”

“No indeed, Professor. For I have come here in large part for a single reason – to put to you a most remarkable proposition.”

And so we sat and we took tea together and Miss Scheherazade Lowenstein put to me that proposal at which she had hinted. It is born, I think, at least in part from guilt at the role that her departed father played, however indirect and unwitting, in my fall from grace. It is, she says, loyalty that drives her, loyalty to her parent’s memory as well as a desire to restore honour to a family name, which is at present mired in disrepute. So she has sought me out to set things right. I have, after only the most perfunctory of protests, acceded to her request and I am, in two days time, to go to London where I shall be put up in the Bostonian Hotel in Bloomsbury and from where, Miss Lowenstein assures me, all that has been taken from me shall be once again restored.

More than that – the specifics of what is to pass between us – I shall not write here. To do so would be to subject them to the cold and unforgiving light of reality whereas at present they have still in my mind the qualities of phantasy and delight. Yes, they have about them the sense of some strange and wonderful dream, which has lingered long into the waking hours.

Читать дальше