It was after midnight when a small child in ragged clothes appeared at my side.

“Does your mother know you are out and about at this time of night?” I inquired.

“I do not know where she is,” he rejoined, “so I do not think she knows where I am.”

“A fair point well made,” I said. “How did you get in here?”

“Through the cloakroom window.”

“How very enterprising. I presume that you have a message for me from Mr Holmes?”

His eyes widened. “You as bright as ’e is, then? Cor!”

I sighed. “What is the message?”

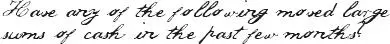

He handed over a dirty scrap of paper. I doubt that Holmes would have let it go in that state; I can only assume that its passage from him to me in the pocket of this ragamuffin had caused its fall from grace.

He kept his empty hand extended. I waited with an eyebrow raised, but he obviously was not going to feel any embarrassment, so eventually I gave him a half-shilling.

“Thanks, mister,” he said with a smile that would have been dazzling if he had not lost most of his teeth. A moment later he was gone.

I queasily unfolded the paper. It said, in Holmes’s characteristic scrawl:

There followed a list of names, some of whom I recognised as being members of high society and the nobility. By sending a footman to retrieve the club’s copy of Who’s Who from the library, I discovered that the remaining ones were largely industrialists and financiers, many of them ennobled or otherwise decorated by our gracious sovereign.

I know that Holmes keeps many files in Baker Street containing information on the criminal underclass (and, indeed, overclass, given that illegal and immoral behaviour spans all levels of society to my certain knowledge). I have my own files, but I keep them in my head. That way they cannot be stolen. Closing my eyes, I walked through the house in which I was born and lived for the first twenty years of my life. In this still-vivid memory I place different facts that I wish to remember in particular places in that imaginary house. I have found that it makes it easier to recall all of the details relating to, for instance, Lord Cathcart if I place them all in a cart, just outside the kitchen door, where the cat used to sun itself in the afternoons. Cat-cart, do you see?

By traversing my imaginary house, I retrieved details of the lives of all the names I knew on the list. A flurry of telegrams sent by another of the club’s footmen to my various agents and informants around this fair city elicited, within a few hours, answers on the names that I did not know.

The sun was shining over the top of the building opposite, casting an unwelcome roseate glow into the club’s writing room, when I was able to pen a simple telegram to Holmes:

All of them on which I have been able to find information have recently taken out bank loans, pawned possessions or made large withdrawals from their accounts.

I could just have said “All of them”, or even just “All” in order to save money, but I knew that Holmes would appreciate accuracy over brevity and I have, sadly, always managed to use a hundred words where ten would have done. Well, I say “sadly”, but when one is paid by the word then one quickly learns to describe things as completely and redundantly as possible. Even simple words like “a” or “the” are cash in the bank, and they are far easier and quicker to write than a word such as “farinaceous”.

I looked at the clock; it was half-past nine in the morning. Assuming it would take an hour for the telegram to get to Baker Street, and that he lived twenty minutes away by cab, I expected to hear from Holmes, or even see him in person, by eleven o’clock at the very latest. Perhaps I was being grandiose (something to which I admit I am prone) but I felt that I had provided him with interesting, if not crucial, intelligence.

It was one minute to eleven when Holmes strode into the club and up to where I was sitting, eating a madeleine cake and sipping at a small, dry sherry. To clarify: it was I who was eating the cake and drinking the sherry, not him. I’m not sure I can ever remember seeing Holmes take sustenance.

“We do not have much time,” he snapped.

“Speak for yourself,” I said, taking a rebellious sip from my glass. “Sit down and tell me what you have discovered. If I am to go anywhere with you then it will be in full possession of the facts, not blindly like poor Dr Watson.”

With poor grace he flung himself into a chair. “Two lines of investigation have intersected,” he said. “Firstly, I have discovered that over the past six months there have been a spate of murders in the capital in which there has been no clear motive and no obvious suspects. All of the deaths occurred in public places, and all were shootings, apparently from a distance.”

“Intriguing,” I said, and indeed it was. “However, given that I know you habitually scour the newspapers for intriguing or eccentric events, and given also that certain sergeants and inspectors within the Metropolitan Police appear to have hansom cabs on standby so that they can easily consult you when they have reached their intellectual limits, which seems to happen with monotonous regularity, I am forced to wonder how this list of mysterious murders has escaped your attention.”

He scowled. “Partly I am to blame for that – I have, until a few days ago, been investigating a case with international ramifications that has quite taken up my attention, involving the Archbishop of Canterbury and a basket of hallucinogenic mushrooms. Also, the police have been conspiring with the owners of the various public spaces to keep the information out of the newspapers. The police – or, rather, their government masters – fear widespread panic at the thought of a random marksman at loose in the capital; the owners of the public spaces – which include parks, theatres and funfairs – also fear a sharp drop in their revenues. While a small unit within Scotland Yard has been tasked with urgently finding this sharpshooter, efforts have been made to suppress any mentions in the newspapers and to class the deaths in other ways – stabbings, muggings and the like – and to dissuade the families of the victims from saying anything. I have also sensed, but have no proof, that bribes have been paid in order to suppress the facts. The police did not consult me for the simple reason that they were forbidden from discussing the details of the case with anybody outside the Yard. For the past few hours, I feel as if I have been navigating my way through a fog that deliberately shifts in order to confound my navigation!”

I nodded, remembering my discussion with the attendant in the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. “You mentioned two lines of investigation. What was the other one?”

“It was the one provoked by your own fact-gathering activities. You recall I sent you a list of names of rich and influential personages?”

“Indeed.”

“Each name on that list has recently paid over a large sum of money to some unidentified person or organisation.”

“I know,” I said. “I told you that.”

“What you had no way of knowing was that each of those names was standing near to one of the unfortunate victims of the shootings at the exact time they were shot.”

Holmes sat bolt upright, fixing me with his challenging gaze. I felt an unaccustomed sense of burning excitement flowing through my veins. “So, what you are suggesting, I presume, is that the shootings were a combination of demonstration and warning,” I said. “I would say that the poor victims had been chosen at random, but that is not true. They were chosen because they were standing near a rich personage, and who would shortly afterwards receive a blackmail demand – ‘Pay us £5,000 or you will be next – and we have shown that we have the capability and the intent’!”

Читать дальше