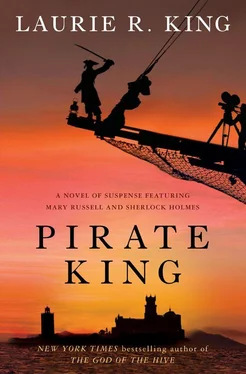

Laurie R. King

Pirate King

Mary Russell – 11

PIRATE KING

a Moving Picture in Three Acts

Director: Randolph St John Warminster-Fflytte

Assistant director: Geoffrey Hale

Assistant’s assistant: Mary Russell

Cinematographer: Will Currie

Choreographer: Graziella Mazzo

THE CAST:

Major-General Stanley played by Harold Scott

Ruth played by Myrna Hatley

Mabel played by Bibi

The Pirate King played by Senhor M. R. X. La Rocha

His Lieutenant, Samuel, played by Sr La Rocha’s Lieutenant

Frederic played by Daniel Marks

THE SISTERS:

Annie

Ginger

Bonnie

Harriet

Celeste

Isabel

Doris

June

Edith

Kate

Fannie

Linda

THE PIRATES:

Adam

Gerald

Benjamin

Henry

Charles

Irving

David

Jack

Earnest

Kermit

Francis

Lawrence

THE CONSTABLES:

Sergeant played by Vincent Paul

Donald

Alan

Edward

Bert

Frank

Clarence

I find myself of mixed mind about this, my eleventh volume of memoirs concerning life with Sherlock Holmes. On the one hand, I vowed when I began writing them that the accounts would be complete, that there would be no leaving out failures or slapping wallpaper across our mistakes.

Nonetheless, this is one episode over which I have considerable doubts – not, let us be clear, due to any humiliations on my part, but because I fear that the credulity of many readers will be stretched to the breaking by the case’s intricate and, shall we say, colourful complexity of events.

If that be the case with you, dear reader, please rest assured that for this one volume of the Russell memoirs, you have my full permission to regard it (and alas, by contagion, me) as fiction.

Had I not actually been there, I, too, would dismiss the tale as preposterous.

– MRH

BOOK ONE

SHIP OF FOOLS

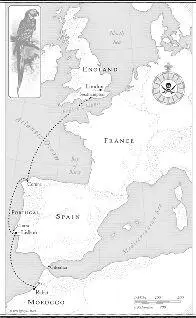

November 6-22, 1924

RUTH: I did not catch the word aright, through being hard of hearing … I took and bound this promising boy apprentice to a pirate .

“HONESTLY, HOLMES? PIRATES? ”

“That is what I said.”

“You want me to go and work for pirates.”

O’er the glad waters of the dark blue sea, our thoughts as boundless, and our souls as free …

“My dear Russell, someone your age should not be having trouble with her hearing.” Sherlock Holmes solicitous was Sherlock Holmes sarcastic.

“My dear Holmes, someone your age should not be overlooking incipient dementia. Why do you wish me to go and work for pirates?”

“Think of it as an adventure, Russell.”

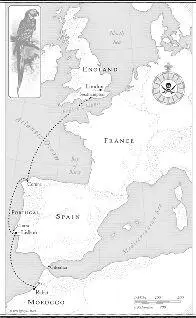

“May I point out that this past year has been nothing but adventure? Ten back-to-back cases between us in the past fifteen months, stretched over, what, eight countries? Ten, if one acknowledges the independence of Scotland and Wales. What I need is a few weeks with nothing more demanding than my books.”

“You should, of course, feel welcome to remain here.”

The words seemed to contain a weight beyond their surface meaning. A dark and inauspicious weight. A Mariner’s albatross sort of a weight. I replied with caution. “This being my home, I generally do feel welcome.”

“Ah. Did I not mention that Mycroft is coming to stay?”

“Mycroft? Why on earth would Mycroft come here? In all the years I’ve lived in Sussex, he’s visited only once.”

“Twice, although the other occasion was while you were away. However, he’s about to have the builders in, and he needs a quiet retreat.”

“He can afford an hotel room.”

“This is my brother, Russell,” he chided.

Yes, exactly: my husband’s brother, Mycroft Holmes. Whom I had thwarted – blatantly, with malice aforethought, and with what promised to be heavy consequences – scant weeks earlier. Whose history, I now knew, held events that soured my attitude towards him. Who wielded enormous if invisible power within the British government. And who was capable of making life uncomfortable for me until he had tamped me back down into my position of sister-in-law.

“How long?” I asked.

“He thought two weeks.”

Fourteen days: 336 hours: 20,160 minutes, of first-hand opportunity to revenge himself on me verbally, psychologically, or (surely not?) physically. Mycroft was a master of the subtlest of poisons – I speak metaphorically, of course – and fourteen days would be plenty to work his vengeance and drive me to the edge of madness.

And only the previous afternoon, I had learnt that my alternate lodgings in Oxford had been flooded by a broken pipe. Information that now crept forward in my mind, bringing a note of dour suspicion.

No, Holmes was right: best to be away if I could.

Which circled the discussion around to its beginnings.

“Why should I wish to go work with pirates?” I repeated.

“You would, of course, be undercover.”

“Naturally. With a cutlass between my teeth.”

“I should think you would be more likely to wear a night-dress.”

“A night-dress.” Oh, this was getting better and better.

“As I remember, there are few parts for females among the pirates. Although they may decide to place you among the support staff.”

“Pirates have support staff?” I set my tea-cup back into its saucer, that I might lean forward and examine my husband’s face. I could see no overt indications of lunacy. No more than usual.

He ignored me, turning over a page of the letter he had been reading, keeping it on his knee beneath the level of the table. I could not see the writing – which was, I thought, no accident.

“I should imagine they have a considerable number of personnel behind the scenes,” he replied.

“Are we talking about pirates-on-the-high-seas, or piracy-as-violation-of-copyright-law?”

“Definitely the cutlass rather than the pen. Although Gilbert might have argued for the literary element.”

“Gilbert?” Two seconds later, the awful light of revelation flashed through my brain; at the same instant, Holmes tossed the letter onto the table so I could see its heading.

Headings, plural, for the missive contained two separate letters folded together. The first was from Scotland Yard. The second was emblazoned with the words D’Oyly Carte Opera .

I reared back, far more alarmed by the stationery than by the thought of climbing storm-tossed rigging in the company of cut-throats.

“Gilbert and Sullivan ?” I exclaimed. “Pirates as in Penzance ? Light opera and heavy humour? No. Absolutely not. Whatever Inspector Lestrade has in mind, I refuse.”

“One gathers,” Holmes reflected, reaching for another slice of toast, “that the title originally did hold a double entendre , Gilbert’s dig at the habit of American companies to flout the niceties of British copyright law.”

He was not about to divert me by historical titbits or an insult against my American heritage: This was one threat against which my homeland would have to mount its own defence.

“You’ve dragged your sleeve in the butter.” I got to my feet, picking up my half-emptied plate to underscore my refusal.

“It would not be a singing part,” he said.

Читать дальше