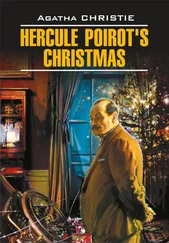

Poirot shrugged his shoulders.

‘Remember this, Hastings, stupidity—or even silliness, for that matter—can go hand in hand [435] to go hand in hand – идти рука об руку; быть неразрывно связанным

with intense cunning. And do not forget the original attempt at murder. That was not the handiwork of a particularly clever or complex brain. It was a very simple little murder, suggested by Bob and his habit of leaving the ball at the top of the stairs. The thought of putting a thread across the stairs was quite simple and easy—a child could have thought of it!’

I frowned.

‘You mean—’

‘I mean that what we are seeking to find here is just one thing—the wish to kill. Nothing more than that.’

‘But the poison must have been a very skilful one to leave no trace,’ I argued. ‘Something that the ordinary person would have difficulty in getting hold of. Oh, damn it all, Poirot. I simply can’t believe it now. You can’t know! It’s all pure hypothesis.’

‘You are wrong, my friend. As the result of our various conversations this morning. I have now something definite to go upon. Certain faint but unmistakable indications. The only thing is—I am afraid.’

‘Afraid? Of what?’

He said gravely:

‘Of disturbing the dogs that sleep. That is one of your proverbs, is it not? To let the sleeping dogs lie! [436] To let the sleeping dogs lie! – Не буди лихо, пока оно тихо!

That is what our murderer does at present—sleeps happily in the sun… Do we not know, you and I, Hastings, how often a murderer, his confidence disturbed, turns and kills a second—or even a third time!’

‘You are afraid of that happening?’

He nodded.

‘Yes. If there is a murderer in the woodpile [437] in the woodpile – (зд.) корень зла

—and I think there is, Hastings. Yes, I think there is…’

CHAPTER 19. Visit to Mr Purvis

Poirot called for his bill and paid it.

‘What do we do next?’ I asked.

‘We are going to do what you suggested earlier in the morning. We are going to Harchester to interview Mr Purvis. That is why I telephoned from the Durham Hotel.’

‘You telephoned to Purvis?’

‘No, to Theresa Arundell. I asked her to write me a letter of introduction to him. To approach him with any chance of success we must be accredited by the family. She promised to send it round to my flat by hand [438] to send by hand – передать с нарочным

. It should be awaiting us there now.’

We found not only the letter but Charles Arundell who had brought it round in person.

‘Nice place you have here, M. Poirot,’ he remarked, glancing round the sitting-room of the flat.

At that moment my eye was caught by an imperfectly shut drawer in the desk. A small slip of paper [439] a slip of paper – листок бумаги

was preventing it from shutting.

Now if there was one thing absolutely incredible it was that Poirot should shut a drawer in such a fashion [440] in such a fashion – таким образом

! I looked thoughtfully at Charles. He had been alone in this room awaiting our arrival. I had no doubt that he had been passing the time by snooping among Poirot’s papers. What a young crook the fellow was! I felt myself burning with indignation.

Charles himself was in a most cheerful mood.

‘Here we are,’ he remarked, presenting a letter. ‘All present and correct—and I hope you’ll have more luck with old Purvis than we did.’

‘He held out [441] to hold out – обещать

very little hope, I suppose?’

‘Definitely discouraging… In his opinion the Lawson bird had clearly got away with the doings [442] to get away with the doings – выйти сухим из воды

.’

‘You and your sister have never considered an appeal to the lady’s feelings?’

Charles grinned.

‘I considered it—yes. But there seemed to be nothing doing. My eloquence was in vain. The pathetic picture of the disinherited black sheep [443] black sheep – паршивая овца, белая ворона

—and a sheep not so black as he was painted—(or so I endeavoured to suggest)—failed to move the woman! You know, she definitely seems to dislike me! I don’t know why.’ He laughed. ‘Most old women fall for me quite easily. They think I’ve never been properly understood and that I’ve never had a fair chance!’

‘A useful point of view.’

‘Oh, it’s been extremely useful before now. But, as Isay, with the Lawson, nothing doing. I think she’s rather antiman. Probably used to chain herself to railings and wave a suffragette flag [444] used to chain herself to railings and wave a suffragette flag – приковывала себя к ограждениям и размахивала суфражистским флагом (типичные действия участниц суфражистского движения, выступавших за предоставление женщинам избирательных прав. Данное движение было распространено в конце XIX – начале XX вв. в Великобритании и США)

in good old pre-war days.’

‘Ah, well,’ said Poirot, shaking his head. ‘If simpler methods fail—’

‘We must take to crime,’ said Charles cheerfully.

‘Aha,’ said Poirot. ‘Now, speaking of crime, young man, is it true that you threatened your aunt—that you said that you would “bump her off,” or words to that effect?’

Charles sat down in a chair, stretched his legs out in front of him and stared hard at Poirot.

‘Now who told you that?’ he said.

‘No matter. Is it true?’

‘Well, there are elements of truth about it.’

‘Come, come, let me hear the story—the true story, mind.’

‘Oh, you can have it, sir. There was nothing melodramatic about it. I’d been attempting a touch—if you gather what I mean.’

‘I comprehend.’

‘Well, that didn’t go according to plan. Aunt Emily intimated that any efforts to separate her and her money would be quite unavailing! Well, I didn’t lose my temper, but I put it to her plainly. “Now look here, Aunt Emily,” I said, “you know, you’re going about things in such a way that you’ll end by getting bumped off!” She said, rather sniffily, what did I mean. “Just that,” I said. “Here are your friends and relations all hanging around with their mouths open, all as poor as church mice—whatever church mice may be—all hoping. And what do you do? Sit down on the dibs and refuse to part. That’s the way people get themselves murdered. Take it from me, if you’re bumped off, you’ll only have yourself to blame.”

‘She looked at me then, over the top of her spectacles in a way she had. Looked at me rather nastily. “Oh,” she said drily enough, “so that’s your opinion, is it?” “It is,” I said. “You loosen up a bit, that’s my advice to you.” “Thank you, Charles,” she said, “for your well-meant advice. But I think you’ll find I’m well able to take care of myself.” “Please yourself, Aunt Emily,” I said. I was grinning all over my face—and I fancy she wasn’t as grim as she tried to look. “Don’t say I didn’t warn you.” “I’ll remember it,” she said.’

He paused.

‘That’s all there was to it.’

‘And so,’ said Poirot, ‘you contented yourself with a few pound notes you found in a drawer.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу