She walked out into the summer morning feeling as if she were the sole survivor of a huge and yet entirely soundless disaster. The sunlight had a sharp, yellowish cast and hurt her eyes. A coal merchant's cart went past, the black-faced coalman standing up on the board with the reins in one hand and his whip in the other and the big horse's nostrils flaring and its lips turned inside out and foam flying back from them. A bus blared, a newsboy shouted. The world seemed a new place, one that she had never seen before, only cunningly got up to look like the old, familiar one. She stepped into a phone box and fumbled in her bag for coppers. She had none. She went to a newsagent's and bought a newspaper, but the change was in silver and she had to ask for pennies, and the newsagent scowled at her and said something under his breath but gave her the coins anyway. She telephoned the salon, but there was no reply. She had not expected Leslie to be there, of course, but there was a tiny comfort in dialing the familiar numbers, and hearing the phone ring in the empty room. Then, before she knew what she was doing, she called his home. Home. The word stuck in her heart like a splinter of steel. His home. His wife. His other life; his real life.

Kate White answered. The English accent was a surprise, though it should not have been. It seemed so strange to her now that they had never met, she and Leslie's wife. At first she could not speak. She stared through the grimy panes of the phone box at the street, the passing cars and buses sliding sinuously through the flaws in the glass.

"Hello," Kate said. "Who is this?" Bossy; in charge; used to being obeyed, to her word being hopped to.

"Is Leslie there?" she asked, and sounded to herself like a little girl, a schoolgirl afraid of the nuns, afraid of the priest in the confession box, afraid of Margy Rock the school bully, afraid of her father. There was a silence. She knew Kate knew who she was.

"No," Kate said at last, coldly, "my husband is not here." She asked again: "Who is this?"

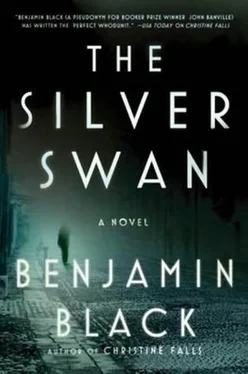

She could not bring herself to say her name. "I'm his partner," she said. "I mean, I work with him, at the Silver Swan."

At that Kate snickered. "Do you, now?" she said.

Another silence followed.

"I need to talk to him," she said, "urgently. It's about the business. I've been to the bank. The manager spoke to me. It's all…" What could she say? How could she describe it? The thing was so vast, so terrible, so hopeless, and so shaming.

"In trouble again, is he?" Kate said, with a sort of trill in her voice, a mixture of bitterness and angry amusement. "That doesn't surprise me. Does it surprise you? Yes, I should think it would. You haven't as much experience of him as I have, whatever you might think. Well, I hope he doesn't imagine I'm going to bail him out again." She paused. "You're in this together, you know, you and him. As far as I'm concerned, you can sink or swim. Can you swim, Deardree ?" And she hung up.

When she got home she decided, although she was not hungry-she thought she might never be hungry again-that she must eat something, to keep her strength up. She made a ham sandwich, but had got only half of it down when she had to scamper to the bathroom and throw it back up. She sat on the side of the bath, shivering, and a cold sweat sprang out on her forehead. The nausea passed and she went downstairs again and got out the vacuum cleaner and vacuumed the carpet in the parlor, pushing the brush back and forth violently, like a sailor on punishment duty swabbing a deck. It had never struck her before that it was not possible to get anything completely clean. No matter how long or how hard she worked at this carpet there would be things that would cling stubbornly in the nap, hairs and bits of lint and tiny crumbs of food, and mites, millions and millions of mites-she pictured them, a moving mass of living creatures so small they would be invisible even if she were to kneel and put her face down until her nose was right in among the fibers.

She remembered the bottle of whiskey that someone had given them for Christmas. It had never been opened. She had put it on the top shelf in the airing cupboard, along with the mousetraps and the caustic soda and the old black rubber gas mask left over from when the war was on and everybody expected the Germans to invade. She turned off the vacuum cleaner and left it there in the middle of the floor, for the mites to crawl over, if they wanted.

The whiskey seemed to her to have a brownish tinge. Did whiskey go off? She did not think so-they were always talking about it being better the older it was. This one had been twelve years old when it was bottled, the same age as the gas mask, the same age as she was when she turned on her Da at last and threatened to tell Father Forestal in St. Bartholomew's about the things he had been doing to her since the time she had learned to walk. Never the same in the flat again after that. The strangest thing was how furious her Ma was at her-her Ma, who should have been protecting her all those years. How she wished, then, that she knew where Eddie was, Eddie her brother who had run away from school and gone to sea when he was still only a boy. At night in bed, listening with a sick feeling for her father's step on the landing, she would make up stories about Eddie, about him coming home, grown up, in a sailor's vest and bell-bottom trousers and a hat like Popeye's on the back of his head, Eddie smiling and showing off his muscles and his tattoos and asking her how she was, and her telling him about Da, and him going up to his father and showing him his fist and threatening to knock his block off if he ever again so much as laid a finger on his little sister. Stories, stories. She drank off a gulp of whiskey straight from the bottle. It burned her throat and made her gag. She drank again, a longer swallow. This time it burned less.

It was late in the afternoon when Kate White came. When she heard the bell she thought it must be Leslie, and she ran to the door, her heart going wildly, from the whiskey she had drunk as much as from excitement and sudden hope. He had come to apologize, to explain, to tell her it was all a misunderstanding, that he would fix it up with the bank, that everything would be all right. When she opened the door Kate looked at her almost with pity. "My God," she said, "I can see what he's done to you." She led the way into the parlor. Kate looked at the vacuum cleaner, and Deirdre picked it up and put it behind the sofa. She could not speak. What was there to say?

Kate paced the floor with her arms folded across her chest, smoking a cigarette in fast, angry little puffs. She had found the photographs, and the letters. Leslie had left them in the bag under his bed-their bed. She gave a furious laugh. "Under the fucking bed, for God's sake!" She supposed he had wanted her to find them, she said. He had wanted an excuse to leave, and this way it would be she who would have to throw him out. She laughed again. "He always liked to leave decisions to someone else." She did not know where he had gone. She said she supposed the two of them had a love nest-he would probably move in there. She stopped pacing suddenly. " Have you somewhere?" Deirdre told her yes, they had a room, but she would not say where it was. Kate snorted. "Do you think I care where you did your screwing? By the way"-she looked up at the ceiling-"did you ever do it here? I'm interested to know."

Deirdre lowered her eyes and gave the barest of nods. Yes, she said, Leslie had stayed one night when her husband was away, in Switzerland. Kate stared, and she had to explain that Billy sometimes had to go to Geneva, for conferences at the head office of the firm he worked for. "Conferences?" Kate said, with another snort. "Your husband went to conferences?" The idea seemed to amuse her. "The poor fool."

Читать дальше