Then he started up the engine, and drove away.

QUIRKE WOKE INTO A GRAY DAWN. HE WAS IN THE OPEN, UNDER TREES. He was cold, and his face was damp with dew. He felt vague pain, vague distress. He wondered if he had been involved in an accident, if he had fallen or been knocked down. A large, dark figure was looming over him, speaking. He could not make out the words. His brain was fogged. He was slumped on some kind of seat, an iron bench, it seemed to be. Yes, it was a bench, and he was by the canal, he recognized the place, for there was Huband Bridge, humped in the grayness. The dark figure put out a great pale hand and grasped him by the shoulder and shook him, and immediately his head began to pound, as if something heavy had been shaken loose in it and was rolling uncontrollably from side to side. "Are you all right?" the figure was saying. It was a Guard, huge and hulking, with a round, bloodless face, standard issue, not unlike Inspector Hackett's. Quirke hauled himself upright on the bench, and the Guard took his hand from his shoulder and stepped back. "Are you all right?" he demanded again. Quirke's mouth was dry, dry and burning, and he had to work his jaws for a moment to get some saliva under his tongue before he could reply. He said yes, he was fine, and that he must have fallen asleep. "You had a few too many," the Guard said gruffly, "by the cut of you." How was it, Quirke found himself wondering, that Guards always seemed aggrieved? Even if you asked one the way to somewhere the fellow would look at you in that grimly startled way, furrowing his brow, as if the simple fact of being addressed constituted a personal affront. To be rid of him, Quirke closed his eyes, and sure enough, when he opened them again, a moment later, so he thought, there was no one there. The light was changed, too; it was stronger now. He was still sprawled on the bench. He must have fallen asleep again briefly, or passed out. He sat up and searched in his pockets for his cigarettes, but could find none. It was coming back to him, gradually, all that had happened. Yesterday had been Tuesday and last night he should have had his weekly dinner with Phoebe, but Phoebe was at Mal's, and he had not dared to call her. Instead he had gone, alone, to the Russell, and eaten dinner alone, and drunk a bottle of wine, and then had gone on to McGonagle's, and downed glasses of whiskey, he could not remember how many. What had followed after that, how he had come to be here on this canal bench, all that was a blank. He rose to his feet, swayingly, that weight still rolling about in his head like an iron ball. There was something urgent he had to do. What was it? Phoebe, yes-he had to do something about Phoebe. He did not know what it was but he knew he must do it. Save her. She was his daughter. He must find a way to bring her back to life. That was how he thought of it, those were the words that formed themselves in his head: I must bring her back, bring her back, to life . He looked both ways along the canal. There was not a soul to be seen. He thought of the long, ashen day ahead of him. He tried to make himself move, to walk, to get away, but in vain; his body would not obey him. He stood there, paralyzed. He did not know where to go. He did not know what to do.

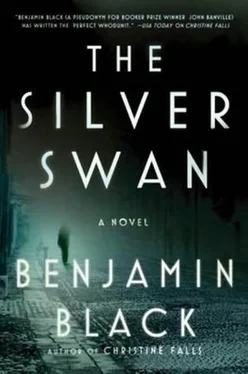

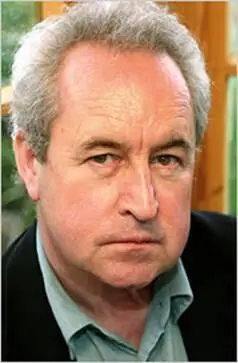

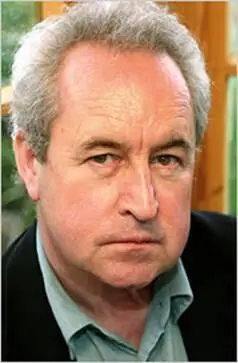

BENJAMIN BLACK is the pen name of acclaimed author John Banville, who was born in Wexford, Ireland, in 1945. His novels have won numerous awards, most recently the Man Booker Prize in 2005 for The Sea . He lives in Dublin.

***