“None that wanted her,” Claire replied. “So we’re going to keep her here, with us.” She looked away, trying to keep her composure.

Diarmuid Lynch asked, “May we see her?”

“Of course.” Anca Popescu’s body was draped, but her face—pale bluish in hue, bruised and scraped—silenced them all for a moment.

Claire reached out and touched Anca’s hair. “She was so often sad. And who could blame her, with the life she had? But if you could see the work she’d done for Martin. There was a quality to it, almost like there was something so immense within her that it couldn’t be contained. I don’t know how else to describe it.”

Nora asked, “Are you planning any sort of observance?”

“Yes,” Claire said. “We’ll wash the body and wake her tonight.”

“If you need help,” Nora said, “I have some experience. I know what to do. Why don’t I come back with you now?”

Following Diarmuid and Claire in the van, with the simple wooden box visible through the back window, Nora felt herself part of an odd funeral cortège, a small procession that wound its way through the hills that had been crossed in turn by chieftains and cattle herders, monks and raiders, croppies and yeomen, all characters in the great book of human events.

Cormac was in the Killowen car park, loading his site kit into Niall Dawson’s vehicle, when he heard a voice behind him: “I need to show you something.”

Cormac turned to see a figure on the bench outside the door. Martin Gwynne seemed to have aged forty years in the space of a day. He stared out toward the oak wood as Niall Dawson joined them. Gwynne said, “Anthony’s back from hospital. And he has something that he’d like you both to see.” He turned to Cormac. “Perhaps you’d bring your father along, too.”

When they arrived at Beglan’s farm, Anthony stepped outside. “You’re all right with this, are you?” Martin Gwynne asked. “I want to make sure, Anthony, because it’s bound to change things. I just need to know that you’re prepared.”

“I uh-uh-AM prepared!” Beglan said, his chin thrusting forward.

The kitchen looked exactly as it had been left by the crime scene investigators yesterday, with remnants of Beglan’s everyday life everywhere: bread crumbs and tea mugs and a buttery knife beside the sink. A basin of water stood on the table, along with a bowl of oak galls and a small Bridget’s cross that Cormac had not noticed before.

Dawson zeroed in on the objects on the table as well and turned to Anthony. “Were you making ink here?”

“No, it’s the cuh-cure,” Beglan said.

“A cure for what?” Dawson asked.

Beglan grimaced and pointed to Cormac’s father, seated at the kitchen table. “Eeh-he can’t talk right. I have a cuh-cuh-cure for it.” He smiled. “I know, cuh-cure myself first, right? But it hum-huh-doesn’t work that way. Un-fuh-fortunately.”

“What way does it work?” Cormac was genuinely curious.

“Be patient. You’ll see the connection very soon,” Gwynne said.

Beglan fetched a bundle from the next room and set it down on the kitchen table. He began peeling back the canvas until he had revealed what was inside. On the table lay an ancient manuscript, its worn leather wrapper closed with three buttons. Cormac could see a knot-work design faintly scratched in the surface of the cover. He glanced at Niall Dawson, who appeared dumbstruck.

“My God,” Dawson finally managed. “Is this… ?”

“A legacy,” Gwynne replied. “An unimaginable treasure, a responsibility laid upon the Ó Beigléighinns, descendants of the little scholar, more than a thousand years ago.”

“And was the book shrine connected to this manuscript?”

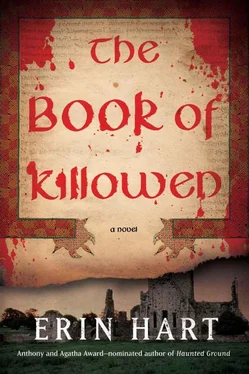

“Yes, but the police have that. The Cumdach Eóghain and its contents had been separated for centuries—Anthony’s grandfather only succeeded in reuniting them in 1947. It’s strange. There’s been so much squabbling over the shrine, with its gold and precious stones, when the real treasure was what lay inside it all those years. Gentlemen, I give you the Book of Killowen.”

Cormac felt a surge of adrenaline. He couldn’t imagine what Niall must be feeling.

“I thought we’d found our missing manuscript when we came across that Psalter in the bog,” Dawson said. “So where does this book fit in?”

“I believe the artifacts you found in the bog—along with this book—tell a story.” Martin Gwynne motioned them to sit. “It’s a story of philosophical rivalry and heresy and hatred. Let me begin with my own story. I came to this place nearly twenty years ago in search of a dazzling creative thinker, an Irishman with a Greek name, Eriugena—it means ‘Irish-born.’ I followed him here, based on a brief passage in a medieval history, a mention of his return, at the end of his life, to the place where he had been born in Ireland. That birthplace was named for the first time. And it was this place, an area known as An Feadán Mór—Faddan More.”

“This medieval history you mention, it wouldn’t happen to be a revised edition of Gesta Pontificum Anglorum by William of Malmesbury?” Cormac asked.

“Ah, so you know of my disgrace,” Gwynne said. “Yes. But I didn’t take the Gesta Pontificum . It disappeared a few days after I’d made my discovery, and I don’t believe that was pure accident. Someone else must have intended to make it look as if I’d helped myself. After all, I was the last to consult that manuscript, at least according to the library records.”

“Who would do such a thing?” Cormac asked.

“I have a few theories, all unprovable. Perhaps archaeology as a field of study is less contentious than medieval history,” Gwynne said. “I hope so for your sake. History and philosophy are full of treacheries, rivalries I knew nothing of. And there are certain factions within institutions like the Church who make it their business to carry philosophical feuds from a thousand years ago into the present. People who feel threatened by the ideas presented in books like this.”

“I can’t believe you actually came here looking for Eriugena,” Dawson said.

“And I was not the only one—others followed the same trail. I should explain that Tessa and I lived here for some time before I resumed my work again,” Gwynne said. “After my dismissal from the library, and our daughter’s… injury—” He paused. “It was really all I could manage, looking after Derryth, and Tessa, as best I could. But after a while I began to see signs, undeniable evidence that the man I sought had been here and had left his mark. The first clue was at the chapel.”

“That doorway,” Cormac said. “The carving of the scribe—the initials IOH . And the letters. Eriugena was one of the few Greek scholars of his time.”

“Yes, and so I began to suspect that there was some little truth to the story of his return. But there was no grave, no name carved in stone, no other physical evidence to say that the figure was Eriugena. So I started digging through the old texts, the Dinnsenchus and the Annals of the Four Masters , and the work of antiquarians like O’Donovan. Through their research, they were able to discover accounts of a mysterious manuscript called the Book of Killowen and trace it right back to the ninth century. O’Donovan reported that the book had been burned, the shrine sold and melted down, because that’s what the Beglans wanted everyone to believe. It was their family’s sacred charge, you see, to protect the book from harm. I only convinced Anthony to show me his book about two years ago.”

Dawson’s gaze was still riveted on the manuscript. He glanced up briefly to address Anthony Beglan. “May I have a look?”

Читать дальше