Erin Hart

THE BOOK OF KILLOWEN

To Bonnie, and to Betty and John and all those who find themselves enfolded in the mysteries of the vitae aeternum

Omnia mutantur, nihil interit.

Everything changes, nothing perishes.

—Ovid,

Metamorphoses , Book XV

PROLOGUE

Domfarcai fidbaidæ fál fomchain lóid luin lúad nad cél.

Huas mo lebrán indlínech fomchain trírech innanén…

Fommchain cói menn medair mass himbrot lass de dindgnaib doss

debrath nomchoimmdiu cóima cáinscríbaimm foróda ross.

A hedge of trees surrounds me:

a blackbird’s lay sings to me

praise which I will not hide…

Above my manuscript—the lined one—

the trilling of the birds sings to me.

In a gray mantle the cuckoo sings

a beautiful chant to me from the tops of bushes:

may the Lord protect me from Doom!

I write well under the greenwood.

—Verse written in the margin by an Irish scribe who copied Priscian’s

Institutiones Grammaticae (a Latin grammar) in the mid-ninth century

Anno Domini 877

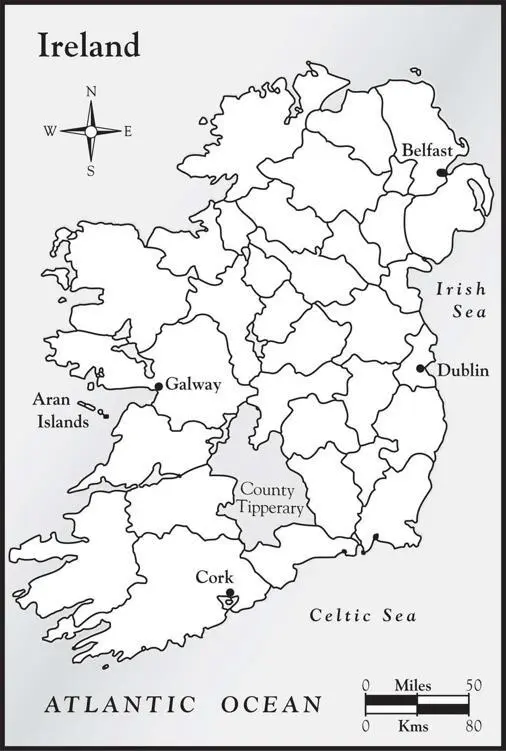

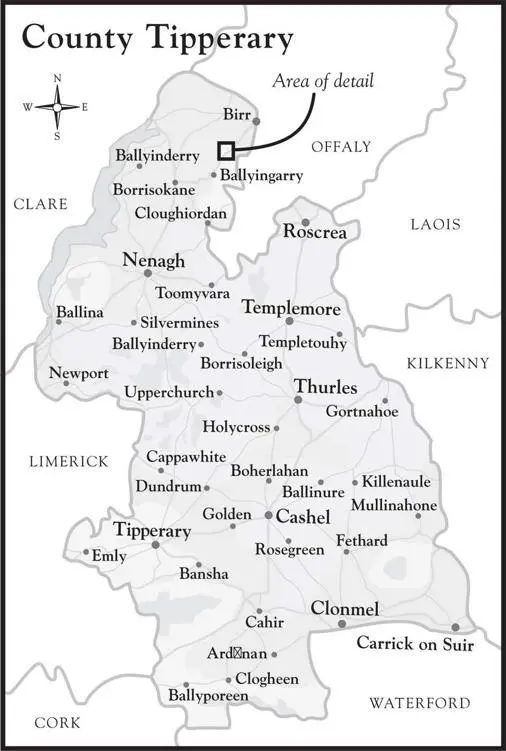

An Feadán Mór, Éile Uí Chearbhaill, Éiru

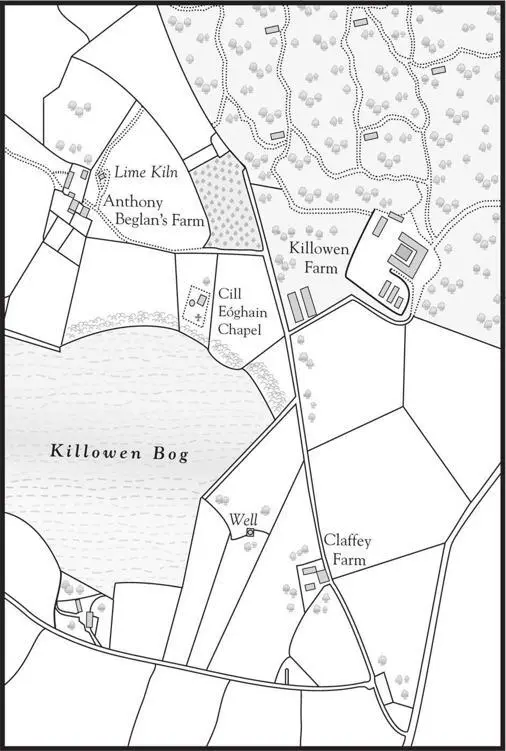

The oak wood was still. All sound seemed soaked up by the thick carpet of moss underfoot. Eóghan stood gazing up into the branches of a giant oak. He stretched as tall as he could, but the gallnuts hung just out of arm’s reach, dangling from a branch above his head. He knew from experience that this particular nut contained the worm of a wasp—and the handiest substance for making good dark ink. Eóghan threw his arms around a stout low-hanging branch and swung his legs up over it. He was an agile climber, having spent many hours in the oak grove near the monastery where he had lived as a child. Soon he was buried in thick sprays of foliage, straddling the branch and inching out toward his quarry, the galls that hung like brown fruit from clusters of leaves. From this perch, he could see his master walking in the morning sun along the edge of the bog where they had spent the night.

Eóghan felt the tension building inside him, then a sudden rush of air as a bewildering noise erupted from his throat. “Cuh-cuh-CUH!”

The master was well used to such outbursts. He turned and raised a hand to his eyes, peering up into the tree. “Ah, you’re awake. God be with you, Eóghan,” he said.

“Cuh-cuh-CUH!” Eóghan shouted again, in reply. Out here in the wood, his voice blended with the sounds of birds and animals, absorbed by the forest floor. Back in the world of men, his yelps and cries had rung out against stone, echoing and reverberating, out of place and rude. Here he was a part of nature, another element in the seamless world of wonders rather than an aberration.

Eóghan could not help what was happening. He had ever been like this. Devil-touched , his own father had called him, and had beaten him sorely nearly every day of his life, in a vain attempt to chase away the demons. When she could bear the beatings no longer, his mother had carried him to the monastery—he was still a child—and persuaded the monks to take him in, to train him up in their ways. The brothers had not been unkind, but in truth they held out little hope for him. They’d thought him simple and put him to work plucking birds for the cook, or gathering nuts and mushrooms in the wood, where his shouting and random gestures could disturb no one but the other wild creatures.

Eóghan inched forward, keeping his oak gall quarry in sight, remembering those early days at the monastery, considering how they had brought him to this place. He had often been set under the kitchen window, where the cook could keep a close eye on him. As he worked, he used to watch the monks strolling from the church to the Scriptorium.

The Scriptorium began to intrigue him. Whenever he was sent to fetch water, he would upend his bucket and stand upon it to peer through the windows, spying on the monks at their writing desks, each with a sheet of calfskin in front him, covered in black marks and designs such as Eóghan had never seen before. At a table in one corner, one brother often worked stitching together calfskin pages, marking them with barely visible lines, or tooling the leather covers that would eventually bind them. Around the walls of the Scriptorium hung leather satchels filled with books, for that was what they were called, these monks’ writings. For months, he had lurked outside whenever he could, watching their painstaking work, fascinated by the brother who made the inks, his crocks full of insects and dried berries, his beakers of wine and blocks of crystal gum. Eóghan had longed to be inside, not just to be near the fire but also so that he could see how everything was done. He had to take great care not to be noticed at his hiding place outside the window. When the shouting fits came upon him, he would stifle the sound with his fist, punching the words and noises back down his throat.

Eventually he had begun to steal into the Scriptorium at night, to gaze upon the work on each writing desk, the pots of ink in every hue. He studied the marks the monks had made, recognizing the same shapes repeated over and over, each page recognizable for its subtly different hand. He traced the shapes of elaborate capitals, studying how the scribes had devised their miraculous designs. To him, every codex hanging from the pegs upon the walls was a living thing, a great soul-cry come to life in a myriad of shapes and colors, in the wild eyes, the bared teeth, and talons of the long-necked peacock, the calf, the dog, the eagle. In his dreams, the animals from the manuscripts moved and spoke, fought fierce battles. It seemed that a kind of secret life was hidden everywhere and in everything, and books were no different.

As he worked in the kitchen, he began to mark out the shapes he’d seen in pig’s blood, or the juice of a beetroot, tracing over and over, seduced by their sinuous outlines, taking care to destroy any recognizable character whenever the cook passed by.

On one of his nighttime forays into the Scriptorium, he found a wooden cask full of oak galls, more crushed in a mortar on the ink maker’s table. He had seen these growing in the grove whenever he was gathering mushrooms or acorns for the cook. So he had begun collecting galls each time he went to the oak wood and secretly adding them to the ink maker’s store. Then one night, as he was leaving his gift of gallnuts, the door of the Scriptorium had burst open.

“There he is!” shouted Brother Alphonsus, the ink maker. “I knew someone had been here. Catch him!”

Eóghan smiled, remembering how he had led the monks on a wild chase that night, leaping over writing desks, spilling ink everywhere. He was younger and more agile than any of them, and by the time they finally caught him, the whole monastery was awake. Faces crowded into the doorway, and the Scriptorium was filled with flickering candlelight.

Читать дальше