Erin Hart

FALSE MERMAID

To my siblings

Julie, Amy, and Jere

and their mates

Colin, Panayiotis, and Sheri

Tri rudan a thig gun iarraidh: an t-eagal, an t-eudach’s an gaol.

Three things come unbidden: fear, love, and jealousy.

—traditional Irish proverb

Is cosúil gur mheath tú nó gur thréig tú an greann

Tá an sneachta go frasach fá bhéal na trá

Do chúl buí daite is do bhéílín sámh

Siúd chugaibh Mary hÉighnigh is í i ndiaidh an Éirne a shnámh.

“ A mháithrín mhilis ” dúirt Máire bhán

Fá bhruach an chladaigh is fá bhéal na trá

“ Maighdean mhara mo mháithrín ard ”

Siúd chugaibh Mary hÉighnigh is í i ndiaidh an Éirne a shnámh.

Tá mise tuirseach agus beidh go lá

Mo Mháire bhruinngheal is mo Phádraig bán

Ar bharr na dtonnta is fá bhéal na trá

Siúd chugaibh Mary hÉighnigh is í i ndiaidh an Éirne a shnámh.

Tá an oíche seo dorcha is tá an ghaoth i ndrochaird

Tá an tseisreach ’na seasamh isna spéarthaí go hard

Ach ar bharr na dtonnta is fá bhéal na trá

Siúd chugaibh Mary hÉighnigh is í i ndiaidh an Éirne a shnámh.

—amhrán traidisiúnta Gaeilge

It seems you’ve faded away and abandoned the love of life

The snow is spread about at the mouth of the sea

Your yellow flowing hair and little gentle mouth

We give you Mary Heaney who has swum across the Erne.

“My faithful mother,” said fair Mary

By the edge of the shore and the mouth of the sea

“A mermaid is my noble mother”

We give you Mary Heaney who has swum across the Erne.

I am tired and will be until dawn

My bright-breasted Mary and my blond Patrick

On top of the waves and by the mouth of the sea

We give you Mary Heaney who has swum across the Erne.

The night is dark and the wind is ill

The Plough can be seen high in the sky

But on top of the waves and by the mouth of the sea

We give you Mary Heaney who has swum across the Erne.

—traditional Irish song

BOOK ONE

MYSTERIOUS DISAPPEARANCE OF A YOUNG WOMAN

THE LAND OF THE BANSHEE AND THE POOKA

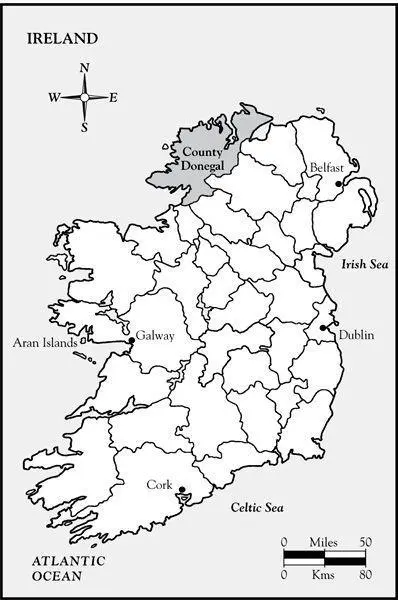

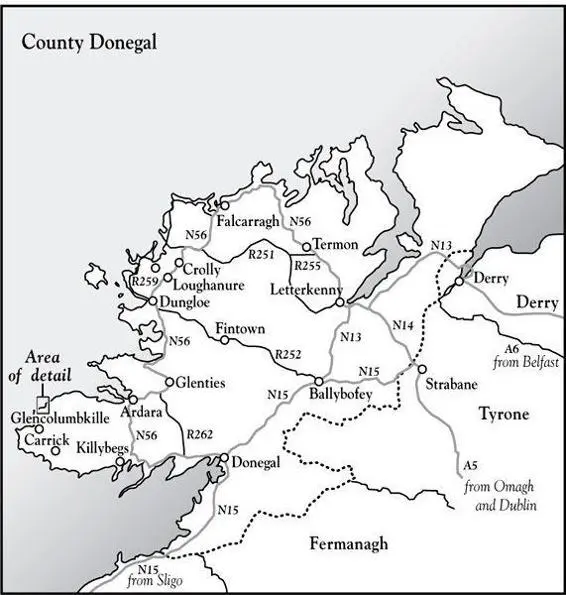

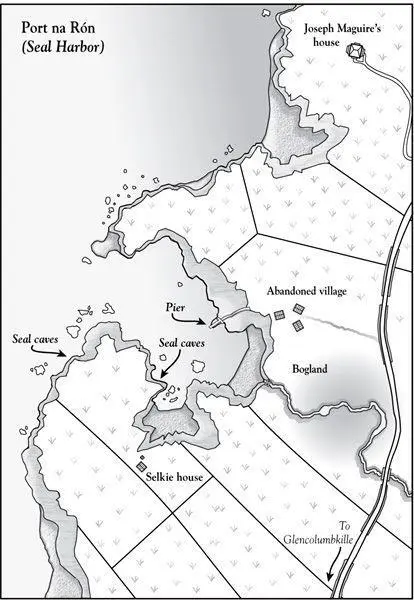

What would read as akin to the fairy romances of ancient times in Erin, is now the topic on all lips in the neighborhood of Ardara and Glencolumbkille. It appears that a young woman named Mary Heaney, wife of a local fisherman, living with her husband and two children in a fisherman’s cottage in the townland of Port na Rón, disappeared on the evening of May the fourteenth, 1896, and has not since been heard of. Up to the present, notwithstanding the exertions of the police and numerous search parties, no account of her, live or dead, has been found.

One event did take place, which has produced all the sensation—the husband swore that the evening before his wife’s disappearance he observed her speaking in a low voice to a wild creature—a seal—outside their cottage window.

There is a local superstition concerning seals who may change their skins at certain periods of their existence, sometimes coming ashore in human form. It is said amongst the local people that upon discovering the skin of such a creature, a ‘selkie,’ while it is in its human form, the person so doing becomes the master of that person or soul, until the creature may regain its own skin again. Of course at the evening firesides such wild stories of ghosts and fairies are devoured with an avidity that only a mysterious occurrence of this kind can produce. Possibly the appearance of the woman in the flesh, by-and-bye, may rob the case of all romance.

—The Ballyshannon Herald, 18 May, 1896

Death was close at hand, but the wounded creature leapt and twisted, desperate to escape. Seng Sotharith pulled his line taut and played the fish, sensing in the animal’s erratic movements its furious refusal to give in. He would do the same, he thought—had done the same, when he was caught.

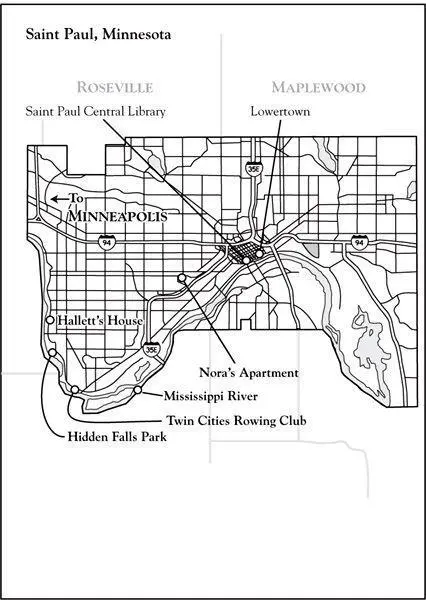

Sotharith sat on the crooked trunk of an enormous cottonwood that leaned out over the water and watched the river flow by. Sometimes as he sat here, suspended above the water, he whispered the words over and over again, intrigued by their strangeness on his tongue. Minnesota. Mississippi . He had been in America a long time—five years in California, and now nearly eight years with his cousin’s family in Saint Paul, but still the music of the language eluded him.

High above on the bluffs, the noises of the city droned, but here he could shut them out. Sometimes on foggy mornings, he looked across the water and felt himself back in Cambodia. He saw houses on stilts, heard the shouts of his older brothers as they played and splashed in the river. The pictures never lasted long, dissipating quickly with the mist. Now the sun was rising behind him, gilding the leaves on the opposite bank. Soon he would have to scale the steep bluff and get to his job at the restaurant. All afternoon and evening, deaf to the shouts and noise of the kitchen, he would wash dishes, wrapped in his thoughts and in memories that billowed through his head like the clouds of steam that rose from the sinks.

He had once harbored a secret ambition to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a doctor. Now, nearly forty years old, he knew it was far too late. But he was determined to learn English at least, to conquer its strange sounds and even stranger writing. It was the one way he could bring honor to his father’s memory.

Sotharith concentrated on his fish, letting the creature run one last time before reeling it in. Coming here helped clear away the images from his dreams, the tangled arms and legs he stepped through every night, the expanse of skulls covering the ground like cobblestones.

When he first arrived in Saint Paul, his cousin had brought him to a doctor, a gray-haired woman with kind eyes. She asked him to speak about the bones, but he could not. No words would come. They all looked at him—his cousin, the interpreter, the doctor. She tried to tell him that he had nothing to worry about, that he was safe here in America. He repeated the English word inside his head: safe . No matter how many times he said it, the sound meant nothing to him. Sotharith only knew that he had to climb down to this riverbank as often as he could, to walk the woods and sandbars below the green canopy and hear the birds at first light.

Читать дальше