“No!” A jagged cry erupted from Tessa Gwynne. All eyes were on her as she leapt up from the table and tried to put herself between Stella Cusack and her husband. “No, it was never shame. I won’t have you saying that. And don’t look at him, don’t—Martin…”

Gwynne’s look pleaded with his wife. “Ah, Tess, you don’t know what you’re doing—”

“I know, my love. I do know.” She turned back to Cusack. “I think you have a daughter, Detective. You cannot know what you would do if someone… if someone brought such grievous harm to your child.”

Cusack said nothing.

Tessa Gwynne continued: “Our Derryth was such an open spirit, so gentle, so full of joy—”

“Until she met Benedict Kavanagh.”

“Until he destroyed her. She met him at that conference in Toronto where Martin spoke all those years ago. I’ve thought about it so much since then, all those philosophers wasting their breath arguing against the existence of evil when he was right there in their midst, that serpent, that villain —” She stumbled, but Cusack reached out to keep her upright. “Martin and I, we didn’t know what had happened. When we returned to England, she tried to stay in touch with him, this man to whom she’d given everything— everything —and he—” Her legs buckled and she fell against Cusack for support. “He tossed her aside, like so much rubbish. My beautiful, beautiful child. Only fifteen years old. And so she tried to kill herself, by swallowing these, a half dozen or more.” Tessa Gwynne brought a fistful of gallnuts from her pocket, her hand shaking. “She believed they were poisonous, you see, just kept shoving them down her throat until she couldn’t breathe anymore. It was too late when we found her, too late to reverse the damage. You see, don’t you, why I did what I had to do? I brought Benedict Kavanagh here. I didn’t know anything about Deirdre, or the baby. Mairéad, I swear, I meant to stop him sooner.”

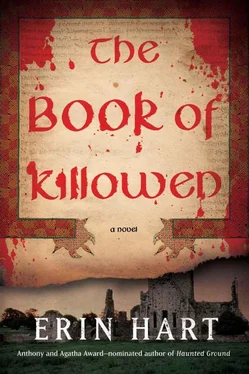

“How did you manage to get Kavanagh down here to Killowen?” Cusack asked.

“It wasn’t difficult. I knew he wanted the book, you see, the fabled Book of Killowen. I knew he’d have done anything to get it. I heard Martin and Anthony talking about it and knew that Kavanagh wouldn’t be able to resist. So I rang and told him that what he was after was here, that it could be his for the right price. I told him to come and see the carving at the chapel, if he didn’t believe me.”

“The figure with the wax tablet,” Niall Dawson said. “The Greek letters. And the initials below, IOH —for Iohannes Scottus Eriugena.”

“And that was the first time Kavanagh came here, eighteen months ago?” Cusack asked.

“Yes. I’d whetted his appetite for the spoils but missed my chance to get him alone. He came, and saw the chapel, and then he escaped. I had to wait more than a year for another opportunity. I couldn’t fail this time. I rang again, asked him to meet me out on the bog, at night. I was to bring the book this time. He didn’t know me—who I was, what I was doing here. I showed him Martin’s copy of the old manuscript, and when he leaned into the boot for his case of money”—her muscles began to spasm, limbs jerking awkwardly—“I hit him,” she said, reliving the horror of it. “As hard as I could, and he crumpled, just like a marionette. I tied his hands and feet, and stopped his breath—one bitter serpent’s egg for every one my child had swallowed. After he was dead, I gave him a proper serpent’s tongue as well.” She fell to her knees, arms and shoulders writhing, her face a grimace.

Martin Gwynne dropped to his knees beside her. “Tessa, no!”

“What’s wrong with her?” Shawn Kearney asked. “Why is she shaking like that?”

Nora darted forward and seized Tessa’s wrist. “Mrs. Gwynne, have you taken something? You must tell us.”

Tessa Gwynne pushed her away. “Leave me alone. Let me talk.” She turned to Cusack again. “You wanted to know about the car, how I managed to bury it. My father was in construction. He taught me himself how to handle a JCB. Always said I was the neatest excavator he’d ever had.”

“And you came across the bog man when you were digging the cutout for Kavanagh’s car,” Cusack said.

Tessa Gwynne nodded, her lips curling back once more in a ghastly grin. “I had no choice, had to put him in the boot. No one would have found them, but for Vincent Claffey grubbing after money in moor peat.” Her breaths were coming shallower. “I’m not sorry he’s dead. As bad as the other, the way he used Anca, his own daughter.” Tessa Gwynne cried out as her body convulsed, her back arching uncontrollably.

Nora took her wrist again, this time checking for a pulse. “Mr. Gwynne, has your wife taken something?”

“I don’t know,” Gwynne replied helplessly.

Nora looked around at the circle of anxious faces. “Did she swallow anything in the last few minutes? Did anyone see?”

Martin Gwynne wept as he tried to still his wife’s body, now wracked with spasms. “I didn’t think… she takes so many tablets. My wife hasn’t been herself these last few months, she’s been ill. Oh, Tessa, my lovely Tess.”

His wife looked up at him, between spasms now, and raised a hand to his face. “I had hoped… all this would pass, and you would never know… but how could I let you or anyone else take the blame? You see that, don’t you, my love? Don’t forget—” Tessa Gwynne’s back arched once more, until it seemed as if her spine would snap. Her husband clasped her to his chest, but her eyes were staring, vacant now. Stella Cusack turned away, her head bowed.

BOOK SIX

Uch a lám,

ar scribis de memrum bán!

Béra in memrum fá buaidh,

is bethair-si id benn lom cuail cnám.

Alas, O hand,

so much white parchment you have written!

You will make the parchment famous,

and you will be the bare peak of a heap of bones.

—Epigram left by an Irish scribe in the margin of a medieval manuscript

Nora pushed through the wide door at the morgue just as Catherine Friel pulled the sheet over Tessa Gwynne’s body on the mortuary table, shaking her head in resignation.

“The poison was mercifully quick. I think we’ll find it’s strychnine, when the toxicology reports come through. She hadn’t much time, in any case. There were some fairly advanced histopathologic changes in her brain and muscle tissue, consistent with multiple myeloma. I’m sure the disease was beginning to affect her quite significantly by this stage. I’m amazed that she had the strength…”

A moment of silence hung between them. Nora thought of the desperate act of a grieving mother, unable to countenance the continued existence of the man she held responsible for her child’s living death.

“I would never condone what she did,” Dr. Friel said. “But that doesn’t mean I can’t imagine what she felt. If it had been my child—”

The door opened, and one of the local mortuary staff stuck his head in. “There’s someone here to collect one of your patients, Dr. Friel—Anca Popescu.” Nora could see Claire Finnerty and Diarmuid Lynch standing just outside the mortuary.

“You can tell them to come through,” Dr. Friel said.

“So you’re taking Anca back to Killowen?” Nora asked Claire. “Does she not have family in Romania?”

Читать дальше