SL’s first letter had opened for Arnold Avery a Pandora’s box of memory and excitement. He had started with WP and examined that memory from every aspect; it had taken him days—and those were days when he was no longer held at Her Majesty’s pleasure, but in the grip of his own; days when Officer Finlay’s blue-veined nose lost the power to provoke him; days when being handed a small paper tub of snot instead of mustard with his hamburger was water off a duck’s back. They were days when he was free.

Then he had gone back to the beginning and savored each of the children anew, and prolonged the ecstasy to almost a month’s duration.

And now this letter.

SL had promised to be a serious correspondent but he was a tease. Like a woman! Like a child! In fact, he wouldn’t be surprised if SL was a woman after all! How dare SL start a correspondence and then send him this nothing of a letter? SL could go fuck herself!

Angrily he folded the single A5 sheet to tear it to pieces—then noticed something on the back of the paper.

Avery frowned and held it up to the light but that made it disappear. He tilted the page until he could see what it was. His heart lurched in his chest.

Arnold Avery hammered on his cell door and shouted for a pencil.

The A5 paper SL had used was good quality. It was better than good quality—it was thick, almost cardlike. Avery had taken art at school and thought it was watercolor paper, with its slightly textured finish.

Avery took a long careful time to rub over the back of the letter with the blunt pencil he’d had to sign for through the hatch.

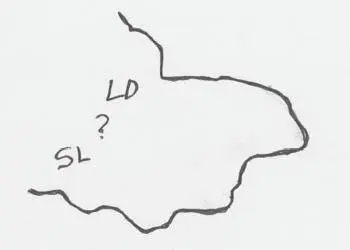

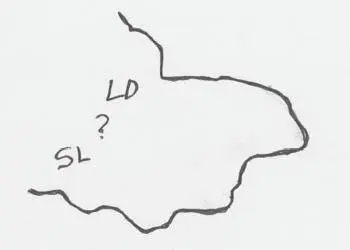

Drawing on a piece of paper laid over this one, SL (whom he now thought of as a man once more, for the cleverness of this communication) had impressed a single wavering, yet somehow deliberate line which travelled crookedly round from the top of the paper in a large loop. Inside the line were the initials LD and a short way below LD were the initials SL.

The only other symbol impressed on the page was a question mark.

Avery almost laughed. The message was childlike in its simplicity. With a line and four letters which would mean nothing to anyone but him, SL was showing him the outline of Exmoor; he was showing Avery he knew where Luke Dewberry’s body had been found and where he was in relation to that, and he was asking again—where is Billy Peters?

Arnold Avery smiled happily. He had his correspondence.

Chapter 11

WHEN HE WAS YOUNGER, GOOD THINGS SEEMED TO HAPPEN TOO fast for Arnold Avery. Things died too easily and too soon. Birds—which he lured to a seed table and caught in a net—were despicable in their surrender. A friend’s white mouse sat meek and trusting as he stamped on its head. The struggles of Lenny, his grandmother’s fat tabby, were explosive at first but faded quickly as he held it underwater in her bright white bathtub.

None of them challenged him. None of them pleaded, begged, lied, or threatened him. Sure, Lenny had scratched him, but that was avoidable; the next cat he drowned—black and white Bibs—tore madly at the motorcycle gauntlets he’d stolen from a car boot sale.

From an early age he read reports of children snatched from cars or playgrounds and found strangled just hours later, and was confused by the waste. If someone went to all the risk of stealing the ultimate prize—a child—why murder it so shortly after abduction? It made no sense to Avery.

At the age of thirteen he locked a smaller boy in an old coal bunker and kept him there for almost a whole day—afraid to damage him but enjoying the control he had over him. Eight-year-old Timothy Reed had laughed at first, then asked, then demanded, then hammered on the doors, then threatened to tell, then threatened to kill, then had become very, very quiet. After that the pleading had started—the cajoling, the promises, the desperate entreaties, the tears. Avery had been thrilled as much by his own daring as by Timothy’s pathetic cries. He had let him out before it got dark and told him it was a test which he had passed. He and Timothy were now secret friends. The younger boy shook in terror as he agreed that Arnold was his secret friend and never to tell.

And he meant to keep that secret.

After a few weeks of wariness, Timothy Reed started to respond to Arnold’s friendly hellos. He could not help accepting the stolen Scuba Action Man or the pilfered sweets. Two months after the bunker incident, Timothy Reed watched as Arnold tortured a weedy nine-year-old bully to tears and a grovelling apology. The bully sent out word in the playground and Timothy was pathetically grateful to have an older, bigger boy as an ally and protector.

And once Timothy Reed looked on him as a hero, Arnold sensed the time was right to call in the kind of favor only a very close—very secret—friend might grant.

Arnold Avery abused Timothy Reed until the child’s reversals of behavior and plummeting schoolwork prompted serious inquiries from his parents and—quickly thereafter—the police.

So Arnold learned his first lesson—that the advantage of animals was that they could not tell.

At the age of fouteen Arnold Avery was sent to a young offenders institution where every night of his three-month sentence—and some days—were spent learning that real sexual power lay not in asking and getting, but in simply taking. The fact that he was initially on the painful end of that equation only heightened the value of this, his second lesson.

He went home, but he never went back.

It took him another seven years before he killed Paul Barrett (who bore a surprising resemblance to Timothy Reed) but it was worth waiting for. Avery kept Paul alive for sixteen hours, then buried him near Dunkery Beacon. Nobody suspected Avery. Nobody questioned him, nobody gave him a second glance as he drove his van round and round the West Country, reading local papers, calling local homes, chatting to local children.

And nobody found Paul Barrett’s body; when they searched, it was near the boy’s home in Westward Ho!

So Dunkery Beacon was a safe place to bury a body, thought Avery.

And he made good use of it.

Chapter 12

THE HEATHER ON THE HILL HAD BEEN DRENCHED INTO SUBMISSION by the rain, and now dripped eerily onto the wet turf as Steven dug.

He dug two holes then ate a cheese sandwich and dug one more.

Since what he’d come to think of as the Sheepsjaw Incident, the digging had lost some of its appeal. That intense high and the crashing low had thrown the hopelessness of his mission into sharp relief. Now every jar of his elbows, every ache in his back, every splinter in his palm somehow seemed more wearing.

At the root of his new bad mood was an itchy discontent that made him distant with Lewis and snappy with Davey. Even out here on the moor where sheer hard work usually drove everything from his mind but a kind of dim exhaustion, he was dissatisfied and grouchy—though there was no one to be grouchy with bar himself, his spade, and the endless moor beneath his feet.

He had not heard from Avery. It had been almost two weeks since he sent the letter with the symbols on the back. Was it possible that he had been too careful? So careful that Avery himself had failed to spot the secret message? Had the killer of Uncle Billy merely read the meaningless words on the front of the paper and tossed it into a bin? Or, if Avery had seen it, had he understood it? In Steven’s murderous mind, he had thought he’d given enough to tempt Avery into answering, but maybe Avery couldn’t crack the code. Or maybe he just didn’t want to. Maybe he didn’t want to play mouse to Steven’s teasing cat. As the days dragged by without an answer from Longmoor, Steven could not suppress a sick feeling of failure. He wished he could tell Lewis of his fears, but he knew this was something he had to keep to himself. Nobody else would understand what he’d done. In fact, Steven could see himself getting into some awkward conversations if he revealed anything about the correspondence.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу