Drug money changed the city’s life and a new social class emerged among the traditionally rich. The traditionally rich began to seek out prosperous mobsters who would purchase their broken industries and family properties for triple their actual value. Luxury cars were no longer exclusive to a certain class. Construction boomed in the city and real estate got very expensive. Nightclubs became the hangout for beautiful women and mobsters. In fact, the most pretentious clubs were built by drug lords. The culture of easy money spread all over the city. Pablo even had hangars for his aircrafts at the Olaya Herrera Airport in Medellín. In the meantime, Escobar and his mafia’s activity began to parallel his political activity. A national magazine put him on their cover and called him “The Robin Hood of Antioquia.”

Pablo Escobar’s exclusive, feared, and powerful security group consisted of Ruben Londoño, alias La Yuca; Luis Alberto Castaño, alias El Choco; Luis Carlos Aguilar Gallego, alias Mugre; and Otoniel González Franco, alias Oto, all from La Estrella; Luis Fernando Londoño Santamaria, alias El Trompón, and José Luis, alias Paskin, from Itagüí; John Jairo Arias Tascon, alias Pinina and Julio Mamey, from Campo Valdés; Carlos Mario Alzate Urquijo, alias Arete, from Aranjuez; Flaco Calavera, from Manrique; and Jorge Eduardo Avendaño, alias Tato, and Carlos Arturo Taborda Pérez from Envigado.

Pablo Escobar enjoyed his money and flew with his friends in his private jet to the carnivals of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. He spent handfuls of money on celebrations and parties. He flew his plane to the United States and gave himself the royal treatment at the best hotels in Miami and other major cities in the country, often accompanied by his family and friends. He rented limousines and helicopters for his transportation needs. On one of his trips, he took his son Juan Pablo to Washington, D.C. and took the famous photo of the two of them in front of the White House. It was his way of saying that he achieved the American dream. He bought a great summer mansion in Miami and also invested in a condo. He often ended these pleasure trips to the U.S. with parties at his hacienda.

Chapter IV

Political Invasion

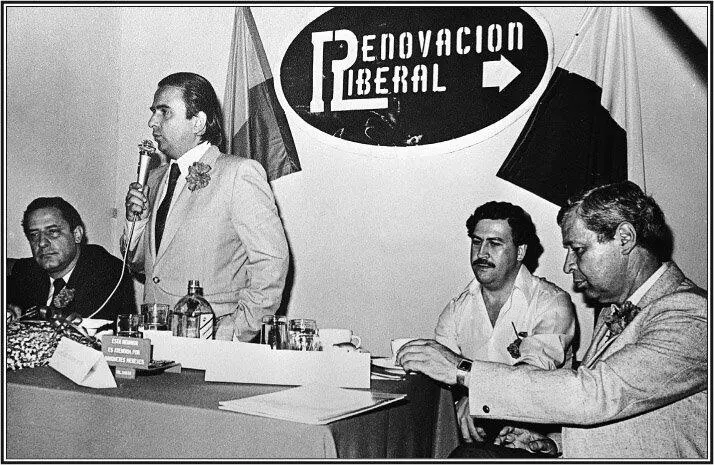

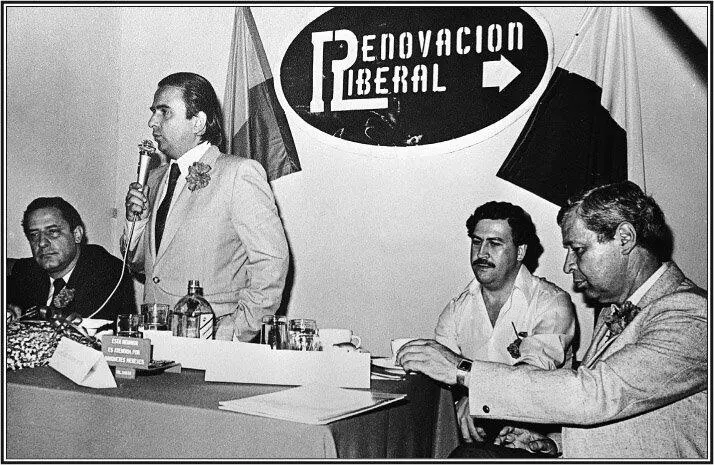

On January 12, 1982, Luis Carlos Galán Sarmiento, the New Liberalism leader, denounced the supporters of the Liberal Renovation of Antioquia movement, which included Pablo Escobar as the the next in line in power, Jairo Ortega being the leading man on the list. Liberal Renovation was supposed to be the movement that represented the New Liberalism in Antioquia.

In a letter to Jairo Ortega, Luis Carlos Galán wrote, “We cannot accept the inclusion of persons whose activities are in contradiction with the moral and political restoration of this country. If you do not accept my conditions, I cannot allow any attachment of your movement’s list with my presidential campaign.” In addition to this letter, Luis Carlos Galán also publicly expelled Escobar from his party during a political gathering at Bolívar Park in Medellín.

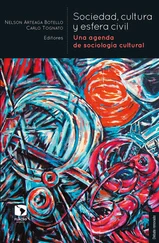

After Pablo was denounced by Luis Carlos Galán’s movement, Senator Alberto Santofimio invited Pablo and Jairo Ortega to join his group; they accepted and joined Alberto Santofimio’s group, also a liberal movement. They then publicly confronted Luis Carlos Galán, condemned his actions in front of voters, and urged his followers not to vote for him.

Pablo, with an energetic speech against oligarchy and a string of good deeds done by his political groups, made his way into congressional elections for the Senate and the House of Representatives. In 1982 the people gave their votes to Jairo Ortega and Pablo Escobar. Jairo Ortega was the leading representative to the House, and Escobar his substitute. But Ortega was Pablo’s puppet; when Pablo wanted to occupy the position, he could order Jairo to let him, and Jairo would.

Pablo’s true ideologist was Alberto Santofimio Botero, because Jairo Ortega was a third-class provincial politician. The voting became dangerous for the same old politicians with Pablo now in the ring. A man with such enormous economic resources as Escobar was a real menace for the Colombian political class. Since Pablo could build entire communities and soccer fields and relieve the hunger of the Antioquian people, he had developed a strong voter base. The lower classes truly saw Pablo Escobar as their savior and benefactor.

Luis Carlos Galán, along with his New Liberalism movement, won a chair in the Senate. This was where the political quarrel between Pablo Escobar and Luis Carlos Galán grew fiercer. In this field, Galán was an experienced opponent, Escobar a novice.

At the time, Escobar was protected by parliamentary immunity; the judges couldn’t touch him, much less the police. Everything was perfect. He had tons of money and a congressional seat. He had reached great power and his movement, with its popular base in Antioquia, found the road open for unsuspected growth.

But El Patrón, in our long hours of conversation, told me how he was given his first low blow. His father, Don Abel Escobar, was kidnapped from his farm in the countryside of La Ceja, Antioquia by a group of delinquents. They were not only testing Escobar, founder of the MAS (Death to Kidnappers), but one of the biggest mobsters in the country, if not the greatest. Pablo retaliated from every possible angle.

He distributed lots of money among backers of the kidnapping industry, hoping for a clue. He also tightened his military fist. Bodies once again filled the streets with the MAS in a rage. City drugstores were warned and offered rewards if they turned in anyone coming to buy the medicine Don Abel used. While this was all happening, the kidnappers contacted Escobar with a taunting message: “If you are so tough, come and take the old man away from us.” They demanded astronomical amounts of money. Pablo responded that the amount they asked for couldn’t even fit in a semi truck. He used military connections to further attack the kidnappers. Every place suspected of holding Don Abel was fiercely searched using helicopters, airplanes, trucks, etc.—anything and everything that was needed.

Pablo Escobar accompanies Alberto Santofimio at a Liberal Renovation political event (Photo courtesy of the newspaper El Espectador – the magazine Cambio )

Even the army helped the Capo 17 17 Drug lord, chief of the mob.

search for his father. In a new call, the kidnappers spoke of negotiating a new sum. The chief of the band continued to mock Pablo during those talks. They finally agreed on sixty million pesos, with the condition that the bills not be of consecutive numbers. Pablo asked the bank for the money and made a record of each one’s number in order to trace them. He varied the bills as the captors had demanded.

The money was then delivered and Don Abel released. But Pablo continued his investigation; in a lucky break, he picked up on the kidnappers’ trace, and found one of the band. He then forced the unlucky individual to call the band’s leader and plan a meeting at a local restaurant. Pablo Escobar and his men finally had their hands on the chief of the band. The poor guy was at Escobar’s mercy.

From the start, the man denied any connection to the kidnapping, but in a brief search they discovered some of the bills from the payment. And then La Yuca switched on a tape recorder where they could listen to the voice of the band’s leader negotiating and making fun of Pablo. The voice was a match.

“So it was you who told me that I would never catch you.”

Читать дальше