A few years later, I returned to Yarumal. My hometown was the same as before. I visited the main square. At the foot of a cold, antique statue was a sign proclaiming: “Wanted: Jhon Jairo Velásquez Vásquez, alias Popeye, Dead or Alive. Reward: $50,000 U.S.” I felt nothing. I left, silent and thoughtful. The sign had replaced the colonel’s honors that I once dreamed of—from then on, I was just a thug.

Chapter II

The Forging of a Gangster

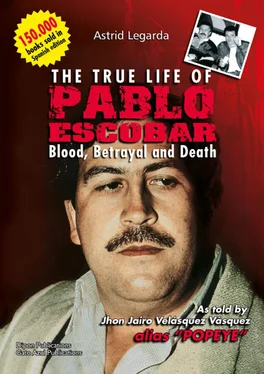

Pablo Escobar never forgot his humble origins. He had a simple personality, free of pretension or a superiority complex. He ate any kind of food without complaint. In fact, he enjoyed a simple plate of rice and scrambled eggs as much as lobster with caviar. He swore he would never trade in his tennis shoes, his blue jeans, and short sleeve shirts for designer clothes or especially those bought at El Éxito. 7 7 The biggest department store chain in Colombia.

He was 5’5”, with black curly hair, a robust build, and a penetrating stare. Pablo was almost always in a good mood. He had a decent vocabulary, and treated his security and work personnel in a friendly way. This was partly why those who knew him intimately loved him.

Although he loved to party and stay up all night, he never got drunk or used cocaine. He only drank beer, which he always drank with three puffs of marijuana. He got high when he was very happy, usually as a reward for the success of some delicate operation. He preferred family reunions over social gatherings with friends or business get-togethers. But, just as he could be the best of friends, he could also be the most ruthless and bloodthirsty of enemies. He never forgave betrayal, and as far as Pablo was concerned, to violate a pact was the worst offense you could ever commit. He was a warrior in every sense.

Son of Doña Hermilda, a schoolteacher, and Don Abel, a humble district watchman, Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born on December 1, 1949, in Rionegro, Antioquia, a chilly town forty-five miles from Medellín. In his youth he lived in the La Paz District, in the municipality of Envigado, twenty miles from the Antioquian capital.

The teenage Pablo was raised in the semi-low class society, strongly influenced by the drug culture. Growing drugs ranging from marijuana to cocaine generated the economy, easily making those willing to dedicate themselves to the secrecy and risk of the business rich. As a young student influenced by his teachers who were involved in social movements and promoted the class struggle, Pablo Escobar led leftist demonstrations. He also participated in rallies where stones were thrown at the police. It was at those heated political demonstrations where he met his future wife, Maria Victoria Henao, La Tata, with whom he fell profoundly in love and whom he never stopped loving until the day he died.

I learned a lot about him on one of those long nights we spent together, hiding out; after preparing and serving each of us his favorite meal of rice mixed with eggs, I dared to ask, “El Patron, how was it that you started this life?”

“Popeye, these questions you ask me . . . come here, I’ll tell you. Everything started when, still a boy, I started a bike repair shop and bike rental in my district. With what this small business produced, I bought myself a Lambretta motorcycle. But I was not willing to use the bike to become a simple messenger; that just wasn’t for me. Instead I used it to rob different commercial establishments. This easy way of making money excited me, and soon my cousin Gustavo Gaviria Riveros and my future brother-in-law, Mario Henao, joined me. Anyway, I planned every one of the little jobs very carefully, paying attention to every detail. I did a lot of preparation work, noting times in the routines of our chosen targets, studying escape routes, and making plans. Above all, we worked with discipline. That way, things turned out well and we undertook the least risk possible. Over time I began to specialize in auto theft. We found someone who worked at a Renault car dealership that would not only make us copies of the car keys, but also give us the buyers’ addresses. Those thefts were easy and we hardly ever faced any danger.

“Then I worked for some time with a smuggler named Alberto Prieto, who taught me the ways of illegal commerce. Afterwards I was caught redhanded stealing a car and was sent to La Ladera Jail in Medellín. I was there for a little while, but it served me well because, as you know Popeye, to be a good bandit it is essential to spend a little time in the school of prison.

“When I got out of jail, I did my first important job with Gustavo and Mario. We kidnapped old Diego Echavarria Misas, a rich businessman.”

“Really, Pablo? You kidnapped him?” I interrupted, “He was my school’s benefactor.”

“Yes, Popeye. And we had to kill him.”

“I remember it was very hard for the whole town. He had a very grand funeral.”

“Please, Popeye, don’t interrupt me. After this we started some modest drug trafficking, selling only small doses of cocaine. Then I traveled by myself across the country and to Ecuador in a Renault 4 to buy five kilos of Peruvian cocaine paste to process in Medellín. Of course, there were lots of police and military checkpoints. To avoid them, I had a brilliant idea. I hired a cheap truck, explaining at the police stops that the car’s engine had broken down. We put the merchandise inside cables and toolboxes, and things went on quite nicely!

“Looking at the pile of money that this business left us, we started bringing great quantities of cocaine in from Peru to send on to the gringos. It was then that I made my first mistake. On June 16, 1976, in Itagüí, I was caught by DAS 8 8 Colombian Administrative Department of Security.

agents when they discovered I had hidden cocaine inside the spare tire of a truck. A retired police major, DAS Chief Carlos Gustavo Monroy Arenas had ordered the operation at the Ecuadorian border. The man had information that some paisas 9 9 People from Antioquia, Colombia.

were taking not only cocaine paste, but also pure cocaine into the country. The detectives Luis Fernando Vasco Urquijo and Jesus Hernández Patiño had found us out. Even though we offered them a large sum of money to let us go, they turned down the bribe and seized our twenty-nine kilos of cocaine. We were imprisoned along with Gustavo Gaviria and the other three men who had accompanied us. Because we were bringing drugs in from Ecuador and the seizure was ordered by an attorney in Pasto, 10 10 Capital City of the Department of Nariño, Colombia.

we were transferred there and detained.

“Almost three months later, on September 10, 1976, after giving our judge a tidy sum of money, he revoked the detention order. We returned to Medellín fully convinced that our life’s calling had to be drug trafficking. I started to see the big picture. No more small cargos—instead, we began using small aircrafts to bring the cocaine paste from Ecuador and Peru to process in laboratories set up by Gustavo and Mario. In the laboratories we turned the paste into pure cocaine and made it ready to be sent to the United States.

“But those despicable detectives Vasco and Hernández kept bothering us. One night, in Envigado, they detained Gustavo and me. They took us away to a hill far away from the populated town of El Pajarito. There they made us get down on our knees and place our hands on the back of our necks. Aiming Smith & Wessons at our heads, they announced they were going to kill us. I, playing along with them, put my arms down and held them to my sides, and tried to convince Detective Vasco that in killing us he would gain very little, but would lose the opportunity to get rich.

Читать дальше