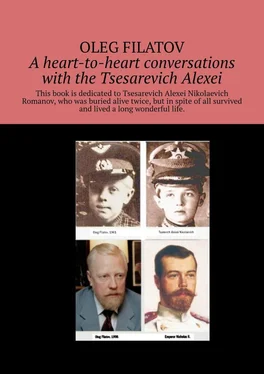

Oleg Filatov - A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Oleg Filatov - A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Мифы. Легенды. Эпос, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:9785005040206

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

drawings, gave him books on chess, fishing, hunting, and history, and embroidered hankies for him. Unfortunately, because we moved often, it was all lost, even though Mama often exhibited her work at school, where she ran the sewing club, and in regional shows, as were our drawings, especially the ones I did with Father, for the holidays. I don’t know what could be found of that now. In connection with Christmas Father often talked about “Christ’s egg” and the suffering of Christ at the hands of bad people. He told us about how the first holiday trees appeared in Russia, about how the holidays were celebrated by the Slavs in ancient pagan times and later, starting with the Russian tsars until Peter the Great, and how he traveled around Russia, a “wandering beggar,” and said that he had to keep in his memory everything that happened to him. And he told us that the Russian tsars loved to hunt in those days. He told us that there was a fast before Christmas, that people prepared themselves for the feast day, and that he used to be like that, he observed Advent, but now few people remember it.

On holidays Kagor wine was served, which my father always called “church wine.” Mama made pies filled with cabbage and with berries, jellied fish, and roast goose or suckling pig. (Father often told us that as a child he and his father “at night” cooked goose “African style,” cooking it without removing the feathers, in day in a bonfire, and that the feathers came off when you removed the day. They also cooked pheasant and quail that way.) Our family loved desserts, we children had cakes, and our parents drank champagne.

We children spent the holidays outside, making snowmen, playing with snowballs, building fortresses out of snow. I spent my whole childhood far from cities, and came to know large cities only later.

In school we studied the history of Russia and the history of the Party. Everyone knows what kind of sciences these were. For him, history was a favorite subject, the basis of his children`s upbringing. He believed that all the misfortunes in Russia were due to a lack of upbringing and education, that this was the greatest of shortcomings and led to misunderstandings, incomprehension, and a reluctance to penetrate to the essence of events, and, in the final analysis, to wars. He used to say that to know history we must read not only textbooks but other books as well. For example, we needed to read about Emelian Pugachev, Suvorov, Catherine II, and Peter I and know much more about them than we got in school. We would ask him whether he knew the history of his own family. And he would tell us how his people grew up on the river Uvod in Kostroma, where his ancestors lived in wooden huts and hunted and fished. “They always hunted with dogs. You must never beat dogs. If, God forbid, anything happened and you offended it, it could betray you during a hunt.” He told us about some distant ancestor of his who went hunting for bear in the winter, but his dogs abandoned him in the forest because he had beaten one of them. The bear was full, of course, and only laid the hunter low with a fallen branch. When the hunter came to, he shot the dogs. “But,” he said, “my people also went after bears without guns. They made an iron ball with spikes and threw it at the bear. He caught it with his paws and the spikes cut into them. Then they had to ride up to him and slit open his belly. That was their idea of entertainment.” (My father was a marvelous marksman and loved to hunt. He used to say that in the old days he had had a dog, a rust – colored Russian hound.) He used to say that all his ancestors were very blond and very fair – haired. “And our name,” he said, “came from Filaret. Once there was a man named Filaret, and we are descended from him.” Today I understand why he said this. “Filaret” comes from the Greek, filat. Later, when we were attempting to sort out his allegories, we asked, “So does that mean that you are the boy who was rescued during the execution of the Romanov family?” And he answered: “Of course not, I descend from Filaret.”

I learned from my father about the execution of the tsar’s family for the first time in about the seventh grade, when we began going through the history of the Revolution. That was when I first heard the name of Yurovsky, who, as my father said, organized the entire affair. I could not understand how the boy could have lived (in his stories, he spoke about the tsarevich only in the third person and called him “the boy”). He used to say that this boy saw the entire crime and what happened afterward and that they hunted for him all the rest of his life. I asked him, “So where did he hide?” And he said: “Under a bridge. There was a bridge there at the crossing, and he crawled in there when the truck shook.” “But how do you know this?” He fell silent. “My uncles told me.” “But who are these uncles?” “Uncle Sasha Strekotin and Uncle Andrei Strekotin, who were in the house guard. After the front, they were stationed there. Oh, and also Uncle Misha.”

(According to the reminiscences of our father, it was during this reloading that Alexei hid under the bridge near the railroad, and, after the truck left, moved along the right-of-way, reaching Shartash Station by dawn. But in Ekaterinburg was more than one bridge near crossing number 184 where the truck could have become stuck in the mud and required unloading.

From the Ipatiev house, two routes led through, or past, the Upper Isetsk works to the Koptyaki road. The first went over the dam at the town pond, a guarded site where a truck on a secret mission would not have wanted to go. But a block downstream on the Iset River, which turned into a brook right below the dam, was a small bridge and next to that, the machine shop rail branch, which led to the Rezhevsky plant. It was about two-and-a-half miles from here to the Shartash Station. Alexei could have covered this distance in two hours in the dark. The search party did not go in that direction and could not have found him.

The other route went from the Ipatiev house on Ascension Avenue to North Street, left over the bridge across another brook, past the new and old stations, past the Upper Isetsk plant, and out onto the Koptyaki road. The truck could have become stuck at this bridge, too. Once again, alongside it was the railroad right-of-way, which continued for about three miles to Shartash Station. Alexei could have covered this distance in two hours as well.

According to the reminiscences of father, on the morning of July 17, the Strekotin “uncles” found Alexei at Shartash Station, and drove him 140 miles to Shadrinsk. The road to Shadrinsk – the terminus of what was at the time a blind branch of the Ekaterinburg-Sinarskaya-Shadrinsk line – was still open. Voitsekhovsky and Gaida’s shock troops were moving toward Ekaterinburg from Chelyabinsk in the south and from Kuzino Station in the west. Easterly directions – toward Tyumen and Shadrinsk – were still open during the week of July 17—24. Alexei reached Shadrinsk with an escort during that week).

He also used to tell me how the bodies of the executed were thrown into tiny mine shafts. “If you want to see how it all was, go watch the movie The Young Guard. There you’ll see large mine shafts, like in Alapaevsk, but you’ll have a notion of those events.” To my question of why I would care about that, he replied: “Why do you need a reason? You’ll know history.” I went to those movies and all my life I remembered the mine shafts the people were thrown down in the film. About the grave he said that he remembered the place, where it was. And that there were no traces left.

It was not until later that I began asking myself how this could be, if this were a boy, a chance witness of a certain episode, he could easily have lost control and cried out or given himself away somehow. In order really to know everything from the beginning (Tobolsk and the Ipatiev house) to the end (the burial site), he had to have passed through the entire chain of events. Could there have been several boys? All of them would have had to have a diseased left foot. How many such boys with a sick foot (specifically a left foot) could end up in the same place at the same time so that one of them saw the execution, another the road along which the bodies were transported, and so on. Which means there was one boy? In addition, there was nowhere to read about the details he told us at that time. This was not publicized or popularized in the official press, and there was no such thing as reading something on the topic in the library, which is why this stuck in my memory especially. He used to talk about these events when the conversation turned to tsars and history, and this was embedded in our memory. My father did not often return to these stories (it would drive anyone crazy to talk about this all the time). He raised us very competently and sensibly, stage by stage, step by step. He spoke about what had happened to him cautiously, so that his story would stay in our memory like little specks. He did not tell us very much about the Revolution. He did say that they broke up and smashed everything, murdered people, and destroyed everything the Russian people had created, because they had lost their faith in God.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A heart-to-heart conversations with the Tsesarevich Alexei» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.